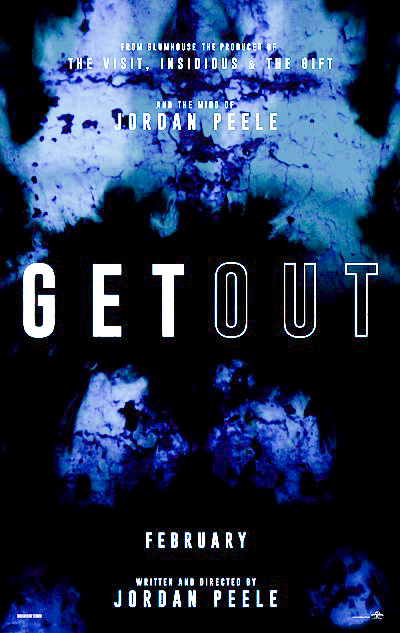

Peele’s “Get Out” Reconciles Horror and Comedy

The genre of horror-comedy is a tricky fusion to tackle, but not for the reasons you’d think. Structurally, the two genres are nearly identical: setups, payoffs, and timing all work together in harmony, whether the director is trying to make an audience laugh or scream. It’s the challenge of balancing out those laughs and screams and not getting stuck in a stylistic quagmire that makes combining the two difficult. “Get Out,” the directorial debut of Jordan Peele of “Key and Peele,” doesn’t entirely avoid leaning on horror clichés for its scares, but the film’s offbeat comedy and timely commentary more than make up for its flaws.

The premise is simple: Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), a black man, drives with his white girlfriend Rose (Allison Williams) out into the country to meet her parents for the first time. They don’t know he’s black, but Rose assures him that they’re “not racist” and would have voted for Obama a third time. Soon after Chris meets the folks (Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener), the horror elements of “Get Out” make themselves apparent. The mildly awkward interactions Chris has with Rose’s very white family turn uncomfortable, creepy, and eventually downright terrifying. The black groundskeeper (Marcus Henderson) and black maid (Betty Gabriel) only render the whole situation eerier, as both possess “Stepford Wives”-style mannerisms that rightly make Chris suspicious of what’s going on.

Even if you’ve only seen one or two sketches from “Key and Peele,” the structure of “Get Out” feels familiar. In their show, Key and Peele thrive off situations where two characters appear to be on different wavelengths in terms of personality. One character appears somewhat normal, and the other is clearly weirder. Key and Peele build up tension using standard methods from cheap horror movies and soap operas—fast cutting, stock music, overdramatic acting—and the artificiality of the atmosphere makes the sketch simultaneously unnerving and hilarious. It all escalates to absurd proportions until the punchline is revealed. Often, the case is that the two characters have more in common than they had thought, or at least a mutual understanding of one another. In the “Clear History” sketch, for example, a distraught Peele tries to keep his cool while his wife asks about his browser usage. Peele’s sweating, flustered reaction to his wife’s questions turns more and more outrageous until, in a brief moment of calm, Peele unwittingly turns the tables on her. The whole sequence happens in less than three minutes.

Extending that 2-to-10-minute bit into an hour-and-a-half-long feature isn’t going to be perfect. But, especially for a directorial debut, it’s worth giving Peele substantial credit for what works.

There’s not a single miscasting in this film, which is remarkable considering each actor is essentially playing two roles: a horror trope and a satirical trope. Kaluuya works well as both the straight man and the only sane one in the room. Williams uses her privileged white girl rep to spin her “Girls” character into something far more sinister. Whitford and Keener play off each other as a chilling neurosurgeon and a hypnosis-wielding psychiatrist, respectively. And Rose’s brother (a very disheveled Caleb Landry Jones) bounces back and forth between overly rambunctious drunk and trigger-happy menace. (His weapon of choice? A lacrosse stick.) Meanwhile, Henderson and Gabriel steal every scene they’re in, Lil Rel Howery shines as Chris’s bumbling best friend employed by TSA, and the supporting cast of rich, white suburbanites is delightfully despicable.

But while the mixture of horror and comedy never feels forced, per se—think of Edgar Wright’s best work—there are times in “Get Out” where the pacing doesn’t always mesh with the film’s weightier themes. While startled jumps abounded in the packed Goldsmith Family Cinema, it’s hard to believe these spooks will have much staying power on the second or third watch.

What’s more, several big twists in the film are revealed abruptly without much buildup. The social and racial commentary embedded in these plot details—especially what this film has to say concerning “woke” white people—doesn’t get the time it needs to fully sink its teeth into the viewer. And the climax, while gleeful and bombastic, is cartoonish while taking itself too seriously, introducing a level of gore that seems out of line with the rest of the film’s style.

When “Get Out” is truly scary, it doesn’t have to go to great lengths to dig at very real, timely fears. The last scare in the film features no blood, nothing supernatural, and no wild stretches of the imagination. It’s simply a visualized reality that some are more aware of than others, and it had the entire theater whimpering in their seats.

“Get Out” doesn’t succeed as a capital-I Important “message film” set in the bygone past, giving us the comfort of distance when it comes to discussing race. It works as a right here, right now horror flick that addresses the realities of brushed-off racism. Even in its lighter moments, “Get Out” never shies away from who its true villains are, and that perspective makes it startlingly refreshing.

Claire Shaffer can be reached at cshaffer@wesleyan.edu or on Twitter at @PlushieAvenger.

简约不简单,大气有内涵!