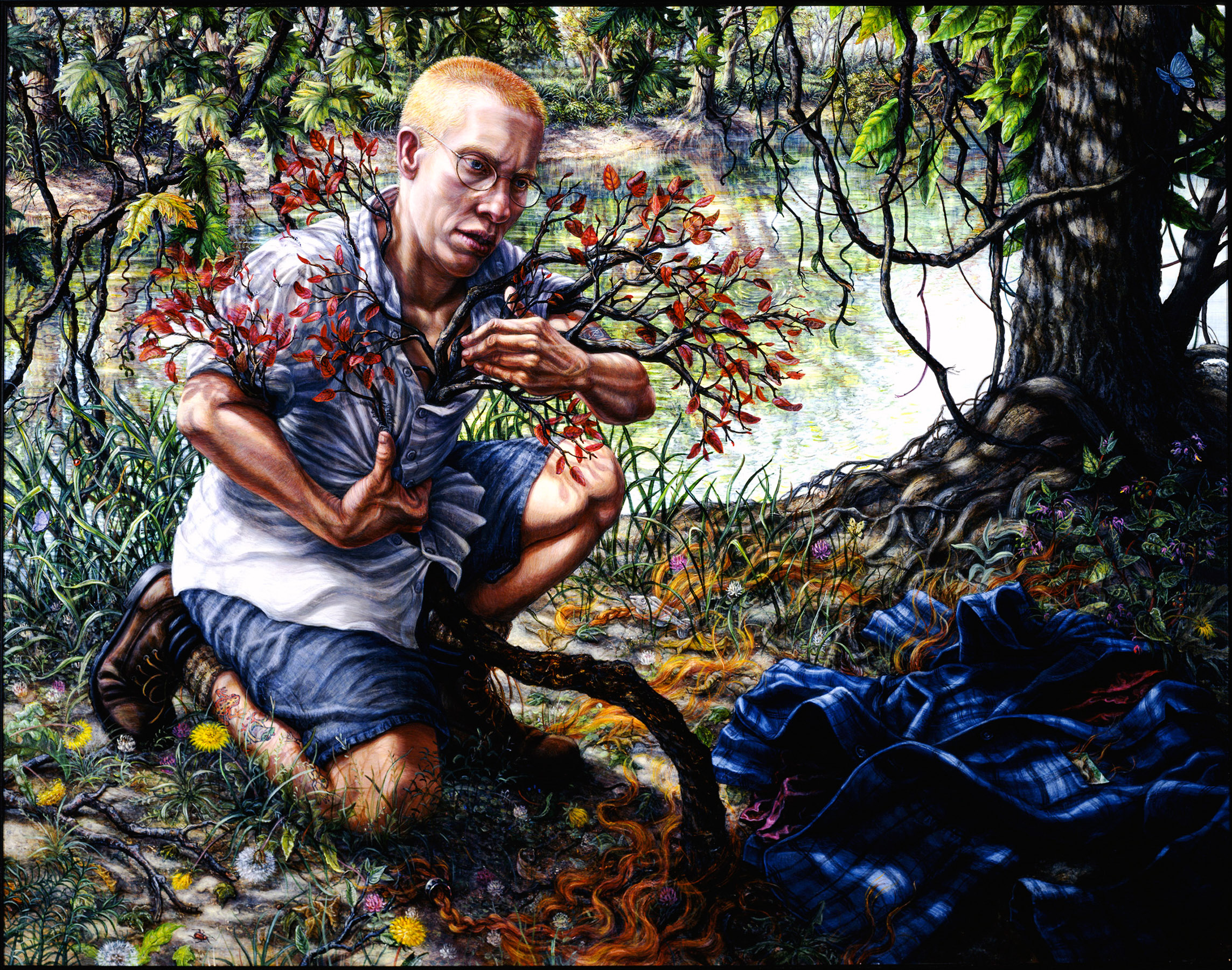

c/o eliclare.com

On Monday, Feb. 13, writer and activist Eli Clare read at Russell House from his new book, “Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure.” The Argus caught up with Clare at the Inn at Middletown to talk about the women’s marches, shame, cure, and the relationship between trans politics and feminism.

The Argus: Your biography on your website and on the posters advertising your talk introduces you as “white, disabled, and genderqueer.” We often think of “disabled” and “genderqueer” as identities, but “white” doesn’t always figure as consciously that way. What are the politics of introducing whiteness?

Eli Clare: I introduce myself that way as a way of modeling that who we are isn’t just a collection of ways we’re marginalized or the intersections at which we experience oppression. Most of us move through the world with some kind of privilege, and the ways we’re privileged often are like the air we breathe: we just don’t notice them.

So by naming myself white, I’m saying, “Pay attention to this. My whiteness is as important for you to know about me as my queerness, as my transness, as my disability.”

A: You participated in a cross-country peace march in the ’80s. In the aftermath of the Women’s March—which was criticized as transphobic and white feminist—I’m wondering: what’s in a march? What’s in a group of people walking together to demonstrate discontent?

EC: There are lots of different goals of marches. In the case of the Women’s March, one was to make our discontent public: “There’s no way we are going to let this happen,” from immigration bans to the shrinking of access to abortion, to the dismantling of the Affordable Care Act, to growing repression and fascism in this country. Another of the goals was, “Let’s demonstrate how big our discontent is”: which was why the numbers became a really big thing. It became important to say that there were nearly three million people on the streets of the U.S. alone.

The only thing I would add in terms of a longer-term march like the peace walk I went on 30 years ago, when I was 23 years old—I really came of age as an activist on the walk—is education. The peace walk I was on became a spectacle. We were a mobile village. We moved six days a week and had a water truck and a kitchen truck and a refrigerator truck….That spectacle provided a doorway into a conversation about nuclear disarmament.

This was in 1986, so Ronald Reagan is in his second term as president. He and Gorbachev can’t sit in the same room. The Cold War is at its height, and there’s no sense that three years later the Berlin Wall would come down, no sense that the Cold War is close to being done….The threat of nuclear war was very, very present. People would come to see the spectacle of us, and then we’d be able to talk about the threat of nuclear war.

A: I was having a conversation with somebody who said, very authoritatively, that intersectionality in feminism is on its way out. I think she was talking about the limits of identity politics, but as someone who’s written a lot about intersectionality, I’m wondering: is it going anywhere?

EC: What’s curious for me about this is the assumption that intersectionality is only about identity. For me, certainly intersectionality is about identity—how it works to bring all of the various pieces of who we are together and say, “These aren’t separate; they impact each other”—but I think that as an activist, most importantly than that is thinking about how different systems of oppression are interlocked.

Meaning, for instance, and this is just one of a million examples, how are racism and ableism interlocked? How do they lock into each other, strengthen each other, bolster each other, contradict each other? And in naming how they’re interlocked, we learn how dismantling any one system of oppression requires dismantling other systems. For me, we won’t be done with intersectionality until all systems of oppression that are interlocked are dismantled. Without understanding, naming, and creating strategies around the ways they’re interlocked, we’re never going to find liberation.

A: Can fighting for the liberation of one group ever inadvertently tackle the entire system?

EC: I often witness, when movements are not being intentional about multi-issue organizing, it becomes single-issue organizing. It becomes, “Let’s just name sexism and work on sexism.” But in naming only sexism, often that sexism is also naming white women at the center. So what I’d say is that it takes a lot of intentionality to do multi-issue organizing. It’s never unintentional.

A: I really want to talk about shame, particularly in storytelling. You’ve written about how pride and shame are in a weird entanglement. But I’m also wondering about the potential power of shame in writing—how a narrator’s shame makes her [sic] more legible and how humiliating oneself through writing can enable connection and maybe, eventually, pride.

EC: Part of what I hear you talking about is the power of writing about shame, and how in writing about shame, sometimes writers are kindling their own shame. In my work, dismantling shame is really important. I don’t think shame is neutral. I don’t think shame is something to be encouraged. I don’t want to build shame into some sort of cultural aesthetic. And that’s largely because of the damage shame does in the communities I live in. I think of suicide, I think of eating disorders, I think of isolation, to name just a few impacts I witness around shame.

By telling stories about shame, we’re breaking down isolation. I want to be careful to not make that sound too simple and too linear, like we tell a story once and it means we’ve moved through that shame. I wish it were that easy. I don’t think it is, but I do think telling stories about shame, and telling stories about resisting shame, is part of dismantling that shame….

The novelist and essayist Dorothy Allison, who wrote “Bastard Out of Carolina,” writes very intensely and provocatively about child sexual abuse and poverty. She says that if you’re afraid of something, you need to write into that exact something. As a writer who sometimes tells intensely personal stories, in my early drafts I’m frequently terrified of what I’m writing and sometimes really embarrassed, unsure whether I’ll be able to show my words to anyone. But often the act of writing into that and through that helps change my shame. So again, the act of telling is part of the resistance.

A: In an interview with Upping the Anti, you said that feminism and trans politics sometimes have trouble talking to each other because feminism seems to reaffirm the gender binary by focusing on power structures that act on different bodies, but trans politics conceptualize gender as a native feeling that arises within us. Does contemporary culture give feeling—feeling male, female, or a different gender—enough legitimacy?

EC: Part of it is that gender is neither completely an authentic internal feeling or a set of power structures. Gender is a really complicated weave of both of those things, and they totally impact each other.

From this answer, your next question could be, “Are you saying you’re not a social constructionist?” And I would say, “Yes.” And then your next question might be, “Well, are you an essentialist?” I would say, “No, I’m a little of both.” Because often this debate between power structures and [the] authentic internal feeling is also named as [essentialism] versus social construction….

To the trans people who are like, “I feel like X, regardless of gendered power structures,” I want to say, “None of us make choices that aren’t impacted by systems of oppression.” And for the feminists who say, “I’m a woman only because that’s what the world has told me, gender is not a choice, gender is something foisted upon us,” to them I want to say, “And what is your connection to your body? Are you saying that you have no connection to and feeling about your gendered and sexed body?”

Those questions are intense, and sometimes I get in trouble for asking them.

A: Is it controversial to say that feelings and power structures are both influential?

EC: When I’m in gender-studies spaces, and we talk about what sounds like essentialism, some folks get really uncomfortable….It seems to me that we’ve swung to this far pole when it comes to social construction, and we may be just beginning to move away from that far extreme.

I remember years ago, I was teaching a trans issues and politics course, and we were reading Julia Serano’s book “Whipping Girl,” and in that book, she talks about the power of hormones. And every women and gender studies major in the class fell apart over the idea over the idea that hormones might be powerful chemicals that could impact gender experience. They were just like, “No, no, no, that can’t be true.”

A: What’s the place of cure in all of this? Is gender a mechanism of cure, a way for us to cure ourselves, or a way for the state to cure us?

EC: So, my brand new book is “Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure.” In the book, I’m exploring what cure means, not just as a medical process, but also as a cultural analogy. Once you start looking for the cure, the cure is everywhere in our culture—in ex-gay reparative therapy, in weight-loss surgery and dieting, in skin-lightening creams for dark-skinned people of color. Cure always depends upon a cultural and/or medical—and when I talk about medical, I’m specifically referring to white, Western systems of medicine—determination of body wrongness, trouble, or brokenness. Cure depends on that. Without damage of some sort, cure can’t exist.

And cure’s really complicated because cure saves lives. Cancer goes into remission, into permanent remission, as if the cancer never existed. On the other end, cure can be extraordinary social control. “Your body-mind [is] not normal, [it] has to be normal, we’re going to make it normal at all costs.” That might go as far as eradicating whole groups of people.

I think about genetic testing and disability-selective abortion. Right now, in the U.S., about two-thirds of pregnancies where testing predicts that the fetus will have Down—notice the language: “predicts,” not guarantees. 60 percent of the time when that prediction is made, genetic counseling ends in a decision to abort the fetus. That says people with Down are damaged. Culturally, we don’t want that damage.

I’m much less interested in any one person’s particular decision about abortion. This isn’t a conversation about the right to choose. I want to remove this conversation from a conversation about being pro-choice. I’m coming to this conversation as someone who thinks access to abortion is crucial and access to self-determination for pregnant women and pregnant people is of the utmost importance. I want us to pay attention to this pattern, and the pattern is that people with Down are considered damaged and ultimately burdensome and worthless. Through the ideology of cure, we want to eradicate Down culturally. We’re going to do that by making sure there are fewer people born with Down. It’s a kind of future-based eradication. Cure as social control can go as far as taking life away, which is paradoxical, right?

I want to return to your question about gender and cure. I don’t think that gender per se is a kind of cure. Gender as a way of being and a system of categorization doesn’t determine which bodies are right and which are wrong. The gender binary does that, but gender by itself doesn’t. But inside the power structures around gender, cure operates all time. I think about reparative therapy for trans people: “Being trans is wrong, and here’s a way to make trans children not trans.”

Clare’s new book, “Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure,” is available from Duke University Press.

Comments are closed