From the roaring tarmac of Bradley International Airport to the momentary silence of the Wesleyan Middle Eastern Student Union in Boger Hall, President Donald J. Trump’s most recent executive order preventing all non-naturalized American citizens from seven countries to enter the United States was palpable. Those banned include people with dual citizenship in any of the seven countries (Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen), permanent residents with green cards, and students with visas.

With the University’s semester starting a day before the executive order was signed, no students are currently believed to be held from entering the United States at this time, according to Dean Mike Whaley and University Manager of Media and Public Relations Lauren Rubenstein. According to both Whaley and Rubenstein, there are eight Wesleyan students on campus from the affected countries, while no members of the Class of 2021 admitted early decision are believed to be from any of the seven countries.

However, for a number of students, the executive order has already hit close to home.

“My parents were supposed to come to the states this weekend, and they can’t now because they have dual citizenship [in one of the seven countries],” a senior said, who wished to speak under the condition of anonymity out of fear of data mining authorized under the Patriot Act. “I just hope they make it for graduation. Then I realize that I’m stuck in the United States.”

At least 1,000 protestors, including some University students, rallied at Bradley International Airport around 1:30 p.m. on Sunday to protest Trump’s ban. The Argus captured much of the proceedings on live video, with speakers including Lt. Governor Nancy Wyman and leaders of the Muslim, Jewish, and Christian faiths, such as Mongi Dhaouadi, executive director of CAIR-CT (Counsel on American-Islamic Relations).

“We are extremely impressed by the number of people that responded,” Dhaouadi said in a press gaggle that included The Argus and The Hartford Courant. “If it tells us anything it tells us that this cause has resonated with the people of this state and we’re in solidarity with people around this nation. The result is very clear.”

Several University students were asked to comment about their experience protesting at the terminal, but no one The Argus spoke to was willing to go on the record, with at least two attendees citing their non-Muslim white identities as a reason not to speak with the press.

Meanwhile, campus Imam Sami Aziz was busy organizing on multiple fronts to protect the University’s Muslim community and local Muslims in Central CT. One of Aziz’s chief efforts has been working with CAIR to provide students with a refugee and immigration lawyer, who he will be holding a training session with on Feb. 1.

Imam Aziz also sees additional steps the University can take to help the Muslim community amid the uncertainty and anxiety they face under the Trump Administration.

“I am hoping Wesleyan will also state a firm commitment against FBI/police intrusion of Muslim students and employees on campus,” Aziz wrote in an email to The Argus. “On campus I am also working on making Muslims feel more welcome by advocating for a larger space, yearly solidarity dinner with Muslim community (as Yale has) and a Muslim community outreach program (as Yale has) through their Muslim Chaplain.”

Before protests at Bradley International Airport got underway, University President Michael Roth ’78 published a blog post and sent an all-campus email indicating that the University intends to protect its students under the ban. While he conceded that the University will have to follow federal law, Roth also indicated that there will be resistance, when possible, with legal partners.

“Our international programs, our financial aid policies and employment programs comply with all applicable Federal and State laws,” Roth writes. “However, we will object to and oppose administrative dictates that violate the law and the Constitution and, if necessary, we will work with others to do so in court.”

Roth added that Public Safety and Admissions will not search for students’ immigration status.

“Our Public Safety Officers do not inquire about the immigration status of the members of the Wesleyan community, and they will not do so in the future,” Roth writes. “Except where we are required to do so by law, we intend to protect our ability to refuse to partner or assist ICE or law enforcement on questions concerning purely immigration status matters. In particular, we are committed to the privacy of all student information, including immigration status.”

Some students at a Wesleyan Middle Eastern Student Union meeting that was open to the public raised concerns about the language of legal compliance in Roth’s statement, citing a lack of confidence in administrative protections under federal pressure. As the meeting went on, students suggested taking both monetary and organizational actions, such as fundraising to cover the cost of living for students who would be forced to stay on campus over the summer and writing to members of the Board of Trustees.

As of the end of the meeting, the demands included assistance with housing costs for students staying over the summer due to the ban, financial aid security for international students (international students don’t receive federal funding for financial aid), keeping a list of legal help for affected students, finding out if there are students or professors currently abroad who are affected, and adding a fundraising designation for students affected by Trump’s policies.

Because of the precedent set by the Patriot Act and deep uncertainty surrounding the Trump Administration’s next move, many students at the meeting with identities rendered more vulnerable under the executive order were cautious to go on the record.

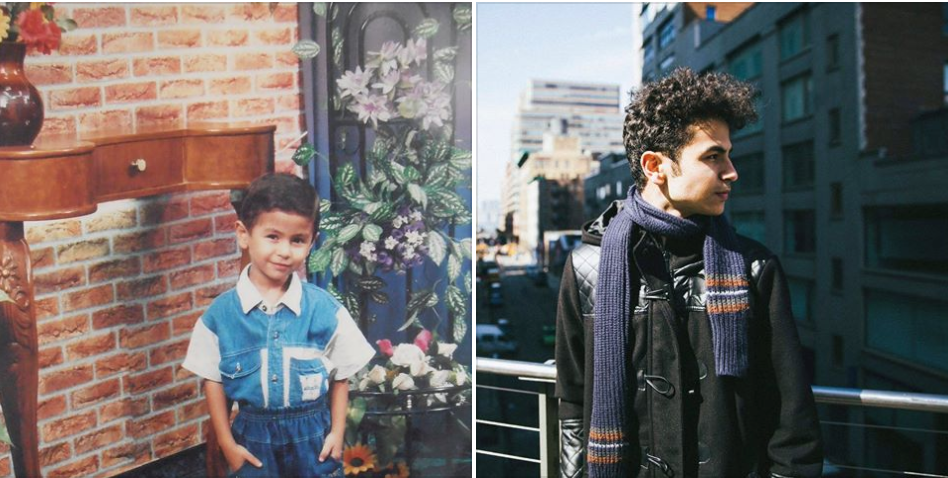

Others, like Ahmed Badr ’20, an Iraqi refugee with U.S. citizenship, issued a statement responding to the immigration ban.

“9 years ago, on May 19th, 2008, The United States welcomed my family with open arms,” Badr writes. “I was 10 years old, full of hope and thought that all American citizens were action stars. I didn’t realize it right away, but we had been given a second chance.”

Badr followed that narrative of a second chance to underscore the importance of refugees and the misperceptions of them by those who support Trump and the ban.

“Because of this second chance, I was able to remind myself and the world that we have more to gain from acknowledging and embracing our differences rather than using them as a means of division,” Badr writes. “This is what a refugee looks like. And this what a refugee can become.”

Despite popular depictions of the University as a monolithic far-left polis, there are indeed Trump supporters on campus, though most would not go on the record regarding the ban or their support of the former real estate mogul more broadly. Mathias Valenta ’20, however, spoke about why he supports Trump and the ban despite fears of repercussions.

Valenta, who is an Austrian citizen and did not vote in the 2016 general election, gained notoriety on campus over the winter break when he posted in an admitted students group for the Class of 2020 inviting students of any political ideology to join him at CPAC (Conservative Political Action Conference), which garnered heated criticism in the comments section. Serving as the treasurer of the recently revived Wesleyan College Republicans, Valenta argued in favor of the immigration ban by pointing to what he saw as a precedent set by former President Barack Obama.

“Obama did the same [ban] in 2011 RE Iraqi immigrants,” Valenta claimed. “The last six presidents have also used this power in some shape or form.”

Regarding the simple use of executive orders generally, Valenta is correct, but Obama’s executive order in 2011 did not ban visa applicants, nor did it establish a religious test. Publications like The Washington Post and The Economist reported that Iraqi refugee applicants were simply reexamined for six months under new vetting procedures after two Iraqis were arrested in Kentucky on federal terrorism charges.

Valenta went on to argue that the ban did not apply to green card holders from the seven countries, and that the executive order was being mislabeled as a “Muslim Ban.”

“The temporary block from regions deemed dangerous does not, if I haven’t misread the order, apply to green card holders who have already undergone very strict scrutiny. The idea being to have a more rigorous vetting process,” Valenta said. “The order is also being mislabeled a Muslim ban, but only includes countries that are considered at risk of terrorist activity. Trump is using the same list Obama did during his 8 years as president.”

Green card holders were prevented from entering the United States over the weekend as Department of Homeland Security Officials struggled to interpret the “in the national interest” clause regarding green card holders. The list Valenta referred to was a State Department change in the U.S. visa waiver program enacted on January 21, 2016.

At the Middle Eastern Student Union meeting, members like Hazem Fahmy ’17, an international student from Egypt, cautioned against relying on the criterion of violence in each country.

“It’s fucking moronic because basically the people who have been saying—there are these charts going around social media—about how no citizen of these seven countries has done a terrorist attack or harmed an American on American soil since 1975, but like ‘these countries’ have, like Egypt—I’m Egyptian,” Fahmy said. “And that’s immensely fucked up because what you’re saying is, it would be more ‘rational’ to put a ban on Egypt and Saudi Arabia and Turkey, and my answer to that is, first, fuck you, but secondly, it is irrational to ban people from a country, period.”

With demonstrations and fundraising efforts planned for later in the week, Middle Eastern Student Union members felt cautiously optimistic about their efforts on campus.

“I want non-affected Wesleyan students to come together so we can educate each other,” Melisa Olgun ’20 said. “We don’t know where [this executive order] will go…I think the general thing is that [the University] is an institution—this is its own little business—and that we need to tread lightly, because there’s a lot of money in this school, and we need to be able to access that money for those affected. There should be some sort of trust established between the student body and the administration.”

This story has been updated since initial publication as a developing story to include further information confirming the status of Wesleyan students from the affected countries.

Jake Lahut can be reached at jlahut@wesleyan.edu and on Twitter @JakeLahut.

Leave a Reply