It’s no secret Donald Glover has had a busy year. It included castings in “Spider-Man: Homecoming” and “Star Wars,” a daring foray into funk with an eleven-track album, and a phone-less concert at Joshua Tree. But Glover did something else this year that transcended this eclectic amalgam: He created a quasi-alternate universe.

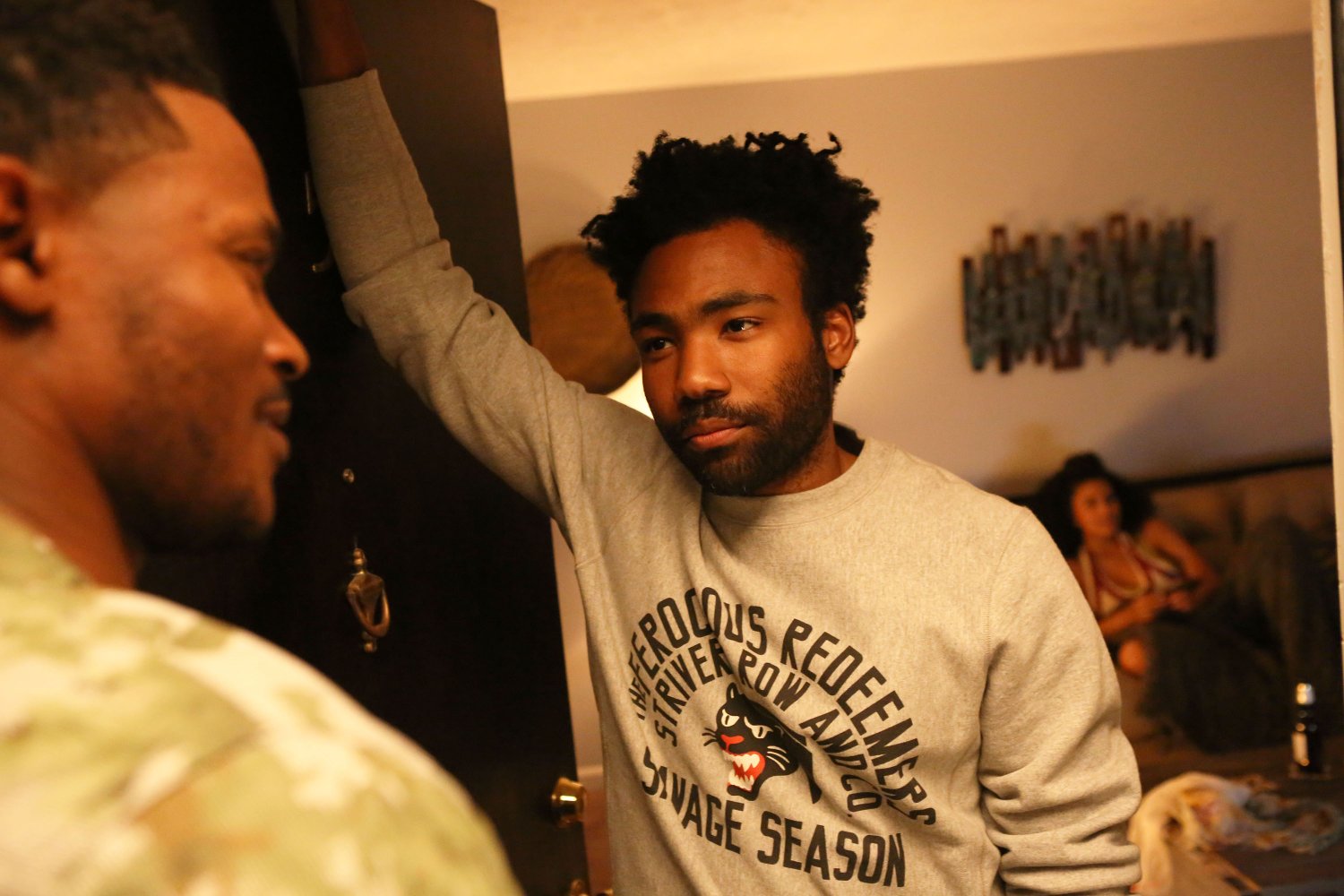

Back in November, Glover’s other major project, FX series “Atlanta,” finished its first season. Glover is the creator, co-writer, executive producer, and star of the show, which follows the lives of two cousins: Earn, played by Glover, and the mid-tier rapper that Earn manages, Paper Boi, played by Bryan Tyree Henry.

Throughout the first season, the show’s writers played with various inventive forms of narration: One episode takes place almost entirely in a nightclub, recreating, to a tee, the hellishness of the experience. Another episode is entirely played out on a made-up TV network called “Black American Network,” which cuts clips of Paper Boi being “interviewed” on the show with actual ads that many viewers initially mistook for real commercial breaks. Each episode’s structure exists not so much for the sake of plot clarity but more to further establish Glover’s quirky, almost-real universe.

“Atlanta” is set in a sort of alternate reality that presents itself materially as realism. There are no vampires, no witches, no superpowers. What the audience sees, however, are Justin Bieber played by a black actor, an invisible car, a not-so-subtle Easter egg of Glover’s latest album artwork in the background of a scene, and other odd breaks in reality that are simply accepted in the world of the show as legitimate.

The first blatant indication that “Atlanta” doesn’t follow the rules of traditional reality is in episode five, entitled “Nobody Beats the Biebs.” The plot line follows Earn and his cousin to a charity basketball game that Paper Boi is getting paid to participate in. Suddenly, a journalist interviewing Paper Boi turns and announces that Justin Bieber has arrived – and the rest of the press rush over to a black teenager (Austin Crute) surrounded by a small posse. The character is as obnoxious and millennial as you’d expect Justin Bieber to be; the only difference is he is Black.

The second glaring violation of reality happens at the end of the ingeniously simple invisible car episode, entitled “The Club,” in which the idea is planted as a preposterous one: A rapper poses in photos as if leaning on, cleaning, and driving an invisible car. The possibility is, logically, dismissed by Paper Boi and the moment is quickly forgotten – until the end of the episode, when people in a parking lot start diving out of the way of what appears to be nothing, and a sitting man speeds forward in the air as if driving an invisible car. The brief throwaway joke that is quickly dropped towards the beginning of the episode is suddenly blown up into a full-on ridiculous version of reality. The move both exemplifies the idiosyncratic tone of the show’s humor and serves to reinforce the fact within the show, the “real” can suddenly be pulled out from under your feet.

There are also less flagrant offenses to the dictations of the real world that simply take angles of reality and exaggerate them into absurdity. Take the bizarre Juneteenth party that Earn’s on-and-off-girlfriend-slash-baby-mama drags him to in order to impress a friend she wants a job from. There, the white owner of the house – clearly intended to express white fascination with and assumptions about Black culture – makes a series of uncomfortable blunders that he believes demonstrate understanding of Black people, from asking Earn where exactly in Africa he comes from to eventually performing an appalling spoken word piece. Here, white attitudes towards Black culture are taken to laughable and disastrous heights in a “Black Mirror”-esque scenario: It doesn’t actually happen, but it’s only one step further than something that does happen.

What exactly is the purpose of these departures from reality? Well, there’s a bevy of possibilities that probably, on some level or another, are all valid. It would seem that each serves a different point. In the case of the Black Justin Bieber, for example, the switch held various levels of meaning, ranging from the benevolence of providing more opportunities to young Black actors who would have never been able to play Justin Bieber in another context, to the idea of turning Bieber’s habitual appropriation of Black culture on its head.

In the case of the invisible car, it’s more for the purpose of humor – it’s actually a TV trope called a brick joke, which consists of an initial setup that is quickly dismissed and a delayed punch line that unexpectedly finishes the joke after the audience has forgotten it. But in a larger context, the invisible car gag is picking up on a thread that the show established with the appearance of Black Justin Bieber, that anything goes in this world, and amplifying it, climbing to new heights of preposterousness.

In an article from last month, New York Times critic James Poniewozik proposed that what he aptly calls “[brief] buckles in the fabric of reality” are necessary for anyone trying to succeed in the music business. This ability to produce something great out of thin air, with their own mind and talent, is just what Glover and his cohorts have created in this new, ninety-percent-real-ten-percent-metaphysical reality from their own imaginations.

It’s most likely, though, that these digressions aren’t meant to espouse any specific sort of point but simply to make viewers think. With regard to the Bieber episode, Stephen Glover (Donald’s brother, who wrote some of the most powerful moments of the show) said in an interview, “Our show’s not really about messages – I know it seems like there are – but we try to give people things that make them ask their own questions.”

And it’s true that, above all, “Atlanta” perplexes. What’s funny about the show is that it’s often framed as a sort of exposé: This is what it’s like to live in Atlanta. This is what it’s like to try and break into music business. This is what it’s like to be Black. But in reality, what it’s showing is that each of those conditions is more complex than anything a TV show can depict.

In an August interview with Rembert Browne, Glover stated, “I wanted to show white people, you don’t know everything about Black culture.”

And there lies the root of “Atlanta’s” relationship with actuality: its tendency to suddenly veer off the metaphysical course of reality. It’s a deliberately subversive trend meant to repeatedly throw off the audience so that they can never assume, never predict, and never fool themselves into thinking they understand. It 180s just when you think you’ve gotten the grasp of it. And when you’re in “Atlanta’s” world, you’re just living it.

Leave a Reply