For Visiting Professor and Artist Eiko Otake in the Dance and the College of East Asian Studies Departments, and Professor William Johnston of History, East Asian Studies, Science in Society, and Environmental Studies, art seems to be anything but an individualized endeavor. When three nuclear reactors underwent level 7 meltdowns in the Futaba District of Fukushima, Japan on March 11, 2011 in the aftermath of a 9.0 magnitude earthquake and ensuing tsunami, all of which devastated the shoreline of northeastern Japan, Otake, who grew up in the country, took a trip back. Upon returning to the United States, Otake urged her colleague and friend Johnston to accompany her on the next visit. This gesture sparked a politically conscious, multifaceted, transcontinental photography and performance art collaboration, which the duo continues to expand upon to this day.

On Nov. 17, the artist team discussed their joint findings, project origins, and methodology in a talk titled “Why Collaborate?—Why Fukushima? Dance, Photography, History.” Johnston opened the night discussing what Otake’s partnership means to him. He also took the time to thank an individual who brought them together in the classroom at Wesleyan.

“It was [Sam Miller’s] foresight, Sam’s determination, to put together the CCR, the Center for Creative Research, which put together Eiko and myself,” Johnston said, whose academic focus is on the history of disease, epidemics, and public health. “For many many years I’ve loved the visual arts with a passion….[Through the CCR, Otake and I] were able to teach a course on Japan and the atomic bomb, which we taught for several years.”

Johnston wove several poems into the talk by the late C.D. Wright, who passed away in January. Johnston opened with a piece of hers titled “Talking Pictures,” which questions and discusses the process between two artists working together to set a photograph’s composition.

The artist team then began discussing their project history. Over the course of an average week on site, according to Johnston, they take anywhere from 3,500 to 6,000 shots.

“[We] just start walking around,” Johnston said of their day-to-day working process. “Sometimes we’ll walk separately, sometimes we’ll walk together. I’m always looking for places. Eiko’s thinking about process and movement.”

“I bring 10 or 20 costumes so I often think about color,” Otake added. “How do I, where do I place my body? In what kind of color?”

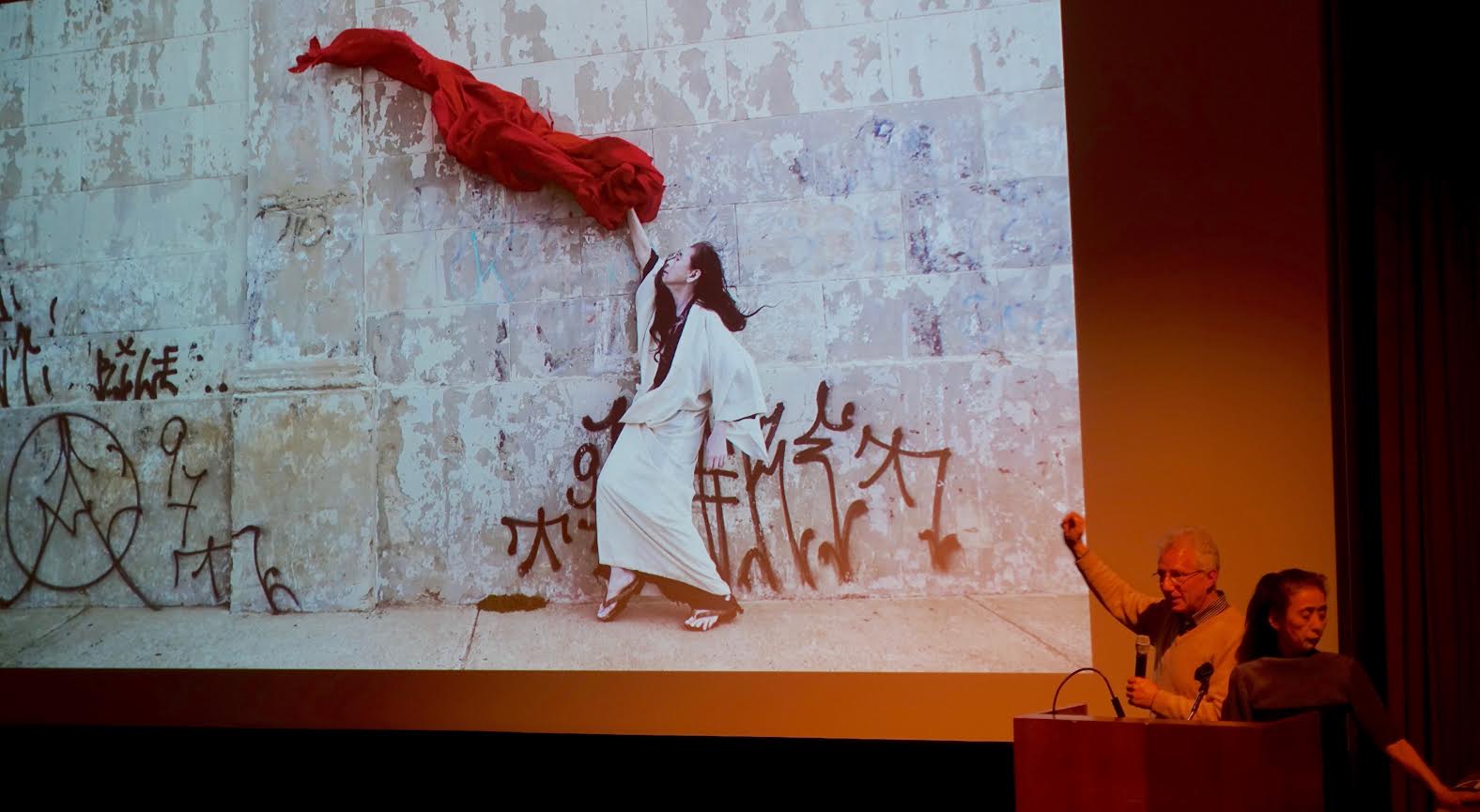

After the duo completed their first trip together to Fukushima, they put together two exhibitions—one of photography, and the other of performance art—in Philadelphia, P.A. In October of 2014, they premiered a collection of photographs at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) titled “A Body in Fukushima.” In many of these pictures, Otake wears a red shawl, which she sewed together with her mother, adding yet another joint creation to the forefront of many of the images.

“I want to emphasize that [‘A Body in Fukushima’] is a collaboration between multiple curators,” Johnston said. “We ended up with clusters of images, which has become a pattern we’ve used over and over in multiple exhibitions.”

“I don’t like to just produce a beautiful photo, I feel defeated,” Otake added. “We can avoid this by not deciding which is the best photograph of that place, instead, how several of them, tens of them together can [communicate] what I felt, or [what Johnston] felt, or possibly the mountains, or the sea.”

Otake and Johnston’s cluster displays make physical the selfless collaborative process that goes into their creations and eventual curations.

“A Body in Fukushima” also made its way to Wesleyan in the late winter and early spring of 2015. Otake and Johnston have begun to photograph outside of Fukushima as well, such as in Santiago, Chile, where they also bought the photography exhibition in January of 2016. Johnston noted that the use of graffiti as a backdrop in the photographs that they shot in Chile was inspired by his understanding of street art as an outlet of expression of the oppression many Chileans faced under Pinochet.

Their collection has also incorporated a subject matter more local to Wesleyan. Johnston and Otake brought their project to the doorstep of a nuclear power plant located at Indian Point 2, which is missing a large portion of its bolts, putting the surrounding areas, including New York City, at risk of facing a partial nuclear meltdown.

Back in that same fall of 2014 in Philadelphia, Otake concurrently debuted a style of performance art, in which, according to her, she behaves oddly, wears worn-down clothing, and wanders around spaces with unsuspecting pedestrians. Dressed almost as if she has just survived the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown, she draws attention to both herself and the neglect these disaster areas in Japan continue to undergo. She delivered a series of three-hour performances titled “A Body in a Station” in Philadelphia’s Union Station. Otake talked of the physical toll these long-form performance art pieces take upon her health, saying that she often gets sick.

“I have to be pitiful before there can be truth,” Otake said of her performances. “I don’t think I can bring hope, but I am there anyway.”

“By presenting her performance and an exhibition of photographs simultaneously, Eiko sought to establish her own body as a link between vastly different stations,” reads the PAFA website description of the 2014 exhibitions. “As such, her body became a conduit between Philadelphia and Fukushima as well as between the museum and the 30th Street station.”

More recently, Otake was a subject in a series of exhibition projects at Danspace in the spring of 2016. She worked alongside a group of resident graduate student artists.

“If I can’t change everything…at least I can share what I care about with my friends,” Otake said.

Otake has a performance art exhibition currently up in St. John the Divine, in New York City, where she is in residency until March 12, 2017.

The artist team has continued to bring their performances and photographs around the world. They continue to put the spotlight back on both Japan and the international community in their failures to step up and find solutions to nuclear energy crises, and advocate on behalf of the usage of alternative, renewable resources. They have continued to return to Fukushima.

“If we keep going back there the project can start to tell a fraction of parts of the story,” Otake concluded.

During the Q&A after the event, an audience member asked if either artist worried about the risks they face in their exposure to such a high concentration of radiation in Fukushima.

It’s a matter of practicality,” Johnston said. “For Eiko and myself, we’re there for a very short period of time. The radiation dosage is relatively small…if there’s a danger for both of us, it’s important that we try and get this message out.”

“I don’t want to just carry the virus,” Otake added. “I want to carry something else. I…carry Fukushima hypothetically [which] has given me something to stand on.”

Harrison Nir ’19, a former student of Otake’s, offered his thoughts on the talk.

“The responsibility and agency she takes in going to Fukushima and choosing to carry something back with her in her body is truly amazing and inspiring,” Nir said.

Just yesterday, on Nov. 21, a 6.9 magnitude earthquake shook the ocean floor near the site of the 2011 disaster. Since then, a tsunami warning has been issued, though several hours later was lifted, and the quake has been described as an aftershock of the one that occurred in 2011. The largest recorded waves have so far reached 1.4 meters, according to the Associated Press. The artists offered comments regarding the news.

“[So] far tsunami reports are not so devastatingly high as in 2011 so it won’t be anything as severe,” Johnston wrote in an email to The Argus regarding the Nov. 21, 2016 aftershock earthquake. “If anybody wishes to make a donation, the [Japanese Red Cross Society] is the best organization. The money is sure to go where it is most needed and they have a proven track record with regard to honesty….My own plans are to find out what is going on in as deliberate [a] way as possible. Am hoping that friends there are okay. We need to take a deep breath, assess what we can do ourselves, and then engage accordingly; but that is true for most everything!”

“I was shaken with fear that Fukushima Daiichi (the first) and Daini (the second) Nuclear Plants might be affected and might develop another catastrophe,” Otake offered in an email to The Argus. “Luckily so far the resulted tsunami was much lower than what happened on March 11, 2011. But this is just another reminder that an earthquake or tsunami should not be regarded as ‘unexpected.’ It is illogical to build a nuclear plant anywhere, because there is always a sure risk of a mechanic failure. But building one in such a place as Japan that often experiences an earthquake and tsunami is insane. ‘How can we survive this craziness?’ I have been asking myself over and over since I first visited the post-nuclear-disaster Fukushima in 2011. I invite you all to imagine damaged nuclear plants standing by the sea. I suggest we learn from our fears and regrets. I sincerely hope we find ways to dismantle all nuclear plants and arms, so we do not destroy ourselves and others.”

Donations to the Japanese Red Cross Society are accepted here.

Upon Johnston’s urging during the presentation, look into fairewinds.org, which tracks nuclear power crises and news.

Emmet Teran can be reached at eteran@wesleyan.edu and on Twitter @ETeranosaurus.

Leave a Reply