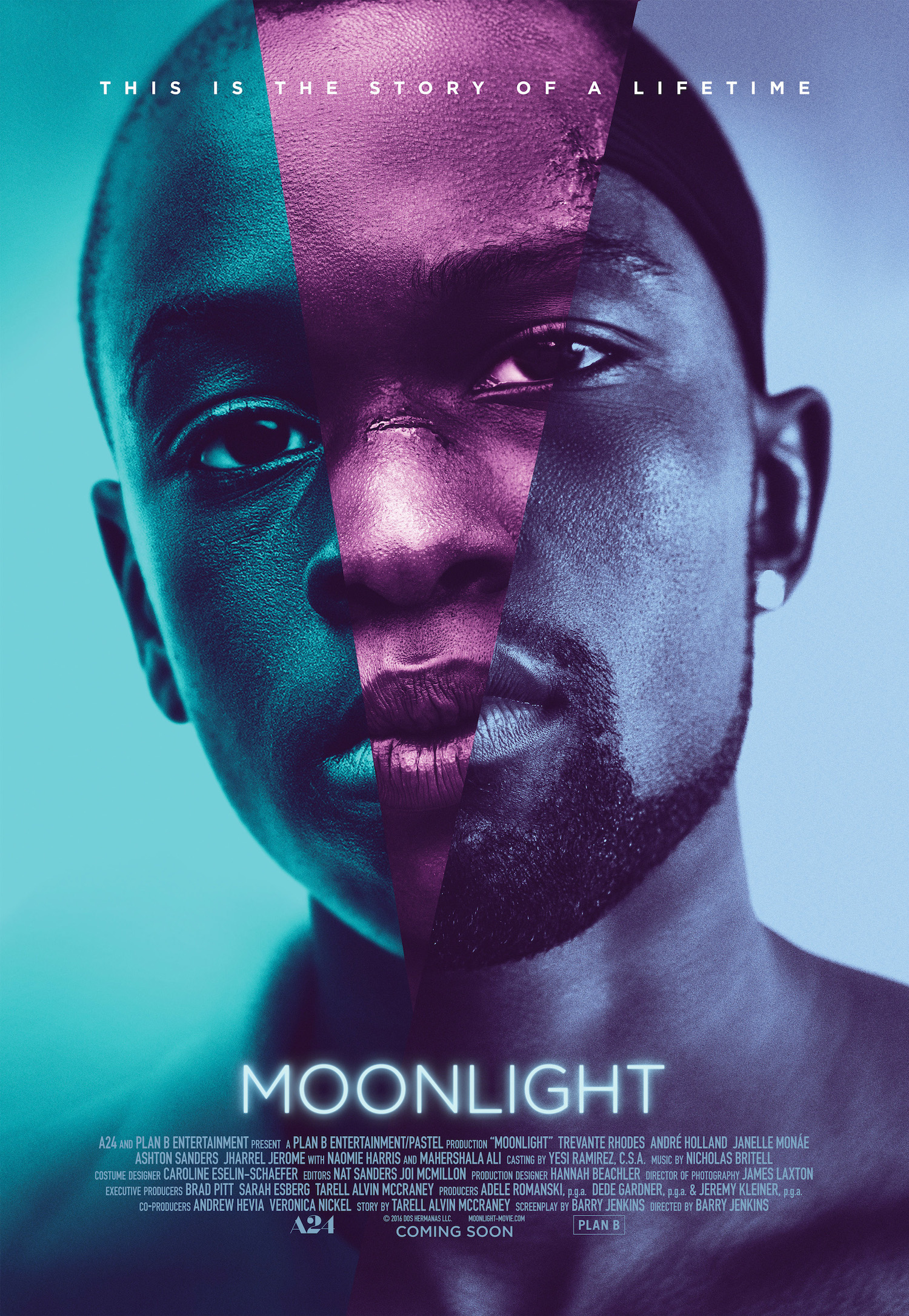

c/o pop-break.com

In a powerful cultural moment, around 400 students packed into the Goldsmith Family Cinema on Wednesday, Nov. 2 to see an exclusive, free screening of “Moonlight,” a cutting edge, low-budget film that chronicles the life of a gay black boy through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. The raw emotion of the film left many in the crowd audibly in tears at several points, and there was a discussion held afterward for those who wanted to talk about the broader implications of the film and the identities with which it wrestles.

Because of the intense anticipation surrounding the film, the cinema was packed by 7:40 p.m. for an 8 p.m. screening. This was quite remarkable given “Wesleyan Time,” where many students show up several minutes late to almost anything.

Many were surprised that the screening was free, but selling tickets would have created potential copyright issues with the film’s distributor, A24.

“Wesleyan Visiting Professor and alum David Laub is a marketing and acquisitions executive at the distributor A24,” said Scott Higgins, Chair of the Department of Film Studies. “He arranged the screening for us because he, rightly, saw this as an important contemporary film and powerful piece of art that speaks to current social concerns. The Film Series does not charge admission on Wednesday nights, and the distributor [A24] offered it to us so long as we did not advertise it off-campus. This was a terrific opportunity that we took advantage of.”

With the nearest theater showing the film over half an hour away in Madison, the early showing of “Moonlight” proved to be a seminal moment for members of the campus community, especially students of color who often don’t see themselves represented in major films.

“Especially because people have commented on the Film Department for being so white, a lot of people were going because like, ‘Oh, this is a non-white film,’ and not really understand how relevant the film is to people or how impactful it can be to people,” Elijah Jimenez ’18 said, who helped facilitate the discussion after the film. “We talked about the role of masculinity, the role of childhood and the removal of black childhood in some senses, and the sexualization of queer people in general.”

Unlike most Hollywood films, white people play a microscopic, if not non-existent, role in “Moonlight.” The only white characters come in the form of police officers who appear for fewer than 10 seconds. The rest of the characters in the film are either black or Latinx, with great exploration into colorism in the Cuban community in the film’s setting of Miami.

The hero, Chiron, played in succession by Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, and Trevonte Rhodes, starts the film as a small boy who is constantly bullied by his classmates. His cinematographic introduction is intense, with a shaking shot from the point of view of the kids chasing him shows a frantic blur, with Chiron’s only identifiable trait being an oscillating blue backpack. He eventually manages to hide from his tormentors, where he meets the film’s second-most poignant character, Juan (Mahershala Ali, of “House of Cards” and “Benjamin Button”).

Ali’s performance of Juan has drawn great critical acclaim, partially because of the performer’s own struggle with being a black actor in Hollywood.

“I was the black guy on the show, that was kind of it,” Ali told Logan Hill of The New York Times in an October profile. ““It felt like there was a diversity box being checked, and if you’re there to check a box, to some degree, then they’re not really going to write for you.”

Yet in “Moonlight,” Ali’s character plays a crucial role in the film’s examination of black masculinity. He gives the performance his all, portraying a complicated character who’s trying to do the right thing when that may be impossible. Ali also delivers some of the film’s most powerful lines, some of which turn into foundational motifs that carry more and more emotion with them as they steadily snowball through all three acts.

Though the film has a stellar cast, ranging from more familiar faces like Ali to many lesser known performers, perhaps the greatest acting feat of “Moonlight” is the tripartite performance of Chiron, an innocent boy whose confluence of black and queer identities make his life torturous. His perceived sexual orientation follows him like a rabid dog in his childhood and adolescence, with scores of his peers chasing after him to beat him up.

“Are you gonna tell him why the other boys beat his ass all the time?” Chiron’s mother, Paula (Naomie Harris) asks Juan, who cannot answer because he knows the ugly truth.

The aesthetics of “Moonlight” are phenomenal in their own right, but the film’s cultural lens is at the foundation of its beauty. Director and screenwriter Barry Jenkins had many difficult choices to make, all of which pay off to make “Moonlight,” not only a remarkable film, but an important historical document. There is no easy way to treat America’s perception of young black men coupled with its homophobia, not to mention its perception of there being greater homophobia within communities of color. There is no easy way to examine a complicated life that can be identifiable to both young black men and a broader audience. Nonetheless, Jenkins pulls it off, and does so masterfully.

As students began to slowly exit the theater, a much higher volume of conversation took place than most nights at the film series. Emotions were raw, people had questions, and some viewers felt uncomfortable. All of this means that “Moonlight” did its job. It got through to people, and more importantly, “Moonlight” proves that contrary to some people’s beliefs, there is no reason why a film cannot be daring and successful without a predominantly white cast.

“Moonlight” will be shown at the Madison theater in Madison, Conn. starting Thursday, Nov. 10. It is currently playing at select theaters in New York City and less than 100 others across the country.

Comments are closed