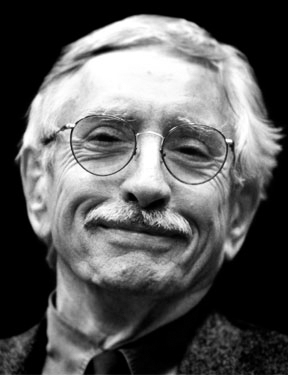

c/o goodmantheatre.org

Last Friday, Sept. 16, the great playwright Edward Albee died in his home in Montauk, N.Y. At 88 years old, he’d had a remarkably lengthy career, with his first play, “The Zoo Story,” premiering in Berlin in 1959. His Broadway debut, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf,” opened in 1962 and won a Tony award for Best Play; it was later adapted into a film directed by Mike Nichols.

I was fortunate enough to see a revival of “Virginia Woolf” when I was in tenth grade. The play follows an old couple, George and Martha (in this revival, played by Tracy Letts and Amy Morton), who return from a dull party, with Martha having invited over a young couple (Carrie Coon as Honey, and Madison Dirks as Nick) for a couple of drinks. The first few minutes of the play are relatively standard: The two couples make a few jokes, establish some tension within their relationships, etc. But rather than write a standard contemporary drama, Albee instead crafted a searing, intense, and horrifying drama. George and Martha are no normal couple. Their constant competition to out-insult each other quickly becomes aggressive and psychotic, bringing Nick and Honey down with them into their sick games. Their son, it seems, has been deeply scarred by their horrible behavior. The play continues down this spiraling path for three acts.

Along this path, many lies are told, relationships damaged, liquor drank, and horrifying truths revealed. It is obvious from the first few minutes that George and Martha are miserable together. By the second act, it is clear that they’re both pathological liars. But, it isn’t clear until the final moments just how intensely disturbed they are. In the third act, while playing one of their many “games” (which are just as disturbing as they sound), George and Martha tell the tale of the upbringing of their son. George has consistently told Martha not to mention him, but she, for the sake of annoying George, has ignored his requests. Not long after, George enters the living room, announcing that he has received a message saying their son had died in a car accident. Martha breaks down, screaming at him, “You can’t do that.”

Their son, it seems, is not real in the slightest; they are an infertile couple who has made up a son as part of a longstanding game between them. Their one rule is to never reveal their son to any outsiders, a rule that Martha breaks early in the play. Nick and Honey leave, and Martha and George, both in a state of terror, embrace each other. With the sun rising in the background, George sings a dumb joke from the party they had attended: “Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (riffing on “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf?”), to which Martha responds, “I am George, I am.”

As someone who didn’t know what to expect from the play, having never seen or read one of Albee’s plays, I was electrified. Never in my life had I experienced a play both so grounded in (seemingly) ordinary characters, and yet so vividly and passionately intense. It had the drama and grandeur of “Hamlet,” with the depressing meaninglessness of “Waiting for Godot.” It was psychologically scarring and deeply human. It had fundamentally changed my view of what theater could be; it was no longer mere entertainment, but something much more vivid.

In a sense, the entire play is about psychological imprisonment based on illusions, both in terms of the characters’ imprisonment and the audience’s imprisonment. George and Martha are trapped by their own emotions and delusional lies about their made-up son; Nick and Honey are entrapped by George and Martha, who try to drag them down into their sick games. The audience, by extension, is trapped within a dark theater, emotionally abused by the psychotic drama on stage. Theater may be a form of escapism, but in “Virginia Woolf,” the audience cannot escape the suffering and terror depicted on stage, all of which is, of course, nothing more than actors performing a script. The play is about the emotional suffering and imprisonment created by lies and delusions, but it simultaneously manages to imprison the audience through three acts of acted-out misery and suffering.

I was so blown away by the production that I ended up asking my grandparents for tickets to a second show as a Christmas present. Luckily enough, I was not only able to get tickets, but I was also able to get tickets for the production’s final performance.

The show started a few minutes late. While most shows start later than their set starting time, this show was delayed longer than most. I assumed that, this being their final curtain, the actors and staff were backstage waxing nostalgic, not quite ready to end their terrific show. Then, as most of the audience was already seated, an elderly man and his assistant strolled down the aisle next to me, sitting a few rows in front of me. Then, the lights finally dimmed, and the show began.

Yes, that man was indeed the great playwright Edward Albee himself.

In retrospect, given his recent passing, it would have made sense to introduce myself to Albee and tell him I was a fan of his work. But other millennials like me had already approached him, and he hardly seemed like he was in the mood to be spoken to. One can’t really blame him. This was, after all, probably the last time he would ever get to see one of his best plays performed.

In a 2013 interview, Albee spoke about his hopes for his legacy after his death.

“It’d be nice [if people remember me],” he said, rather stoically. “Although I’m not going to care much…Because I know I’m not going to be around to experience it.”

Considering how blisteringly intense his writing was, Albee was oddly humble. He wasn’t interested in fame or glory, but only in his writing. “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf,” regardless of whether or not Albee cares, will likely be remembered forever. I highly doubt anyone who sees it could ever forget it.