c/o www.rogerebert.com

The connection between dreams and waking life is very much at the core of the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Perhaps most famous for his film “Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives” (which won the Palme D’Or at Cannes in 2010, thus becoming the first Thai film to do so), Weerasethakul creates films with a strong sense of transcendent serenity, as if life were unfolding as a pleasant but hazy dream. The scenes drift quietly from one to the next like a rolling river, pulling the audience along in its sleepy current.

The feelings elicited from Weerasethakul’s films have often been linked to the practice of meditation. He was raised in the tradition of Thai Buddhism, and, as such, the practice of Vipassana meditation (focused on breathing and mindfulness) has been an integral part of his life and his filmmaking process. In fact, Weerasethakul focuses solely on meditating and writing when scripting his films. For him, the practice is no longer religious, but an exploration of the mind.

Weerasethakul once said, ‘To me, meditation is simply a profound way of tapping into the mysteriousness of the mind and how we remember things. It’s like if you don’t take a shower every day you will soon give out bad smells. I think it’s the same for the mind. When you meditate you readjust the system, and maybe it’s the same as why we dream—to clear something out.”

This exorcism-through-dream almost literally manifests itself in his newest film, “Cemetery of Splendour.” The film centers on a nurse named Jenjira, an older woman, who tends to several soldiers who have become afflicted with a mysterious sleeping sickness. She befriends one of the soldiers, named Itt, and a psychic medium, Keng, who can view the dreams of the men as they sleep. Through Keng’s reading of the sleeping men’s dreams, we learn that the town was built upon the location of a great palace and a former battleground. Long-dead kings are using the spirits of the soldiers to fight their battles in the afterlife. Though the soldiers wake for a time, they always return to their sleep and continue to fight, forever.

It is easy to see the metaphorical subtext of the film even without a great knowledge of Thailand; the film takes on a political subtext and a critical view of certain aspects of Thai culture and government. Weerasethakul has had a difficult relationship with his home country over the years, having struggled with censorship and a lack of interest in his films: the head of Thailand’s Ministry of Culture’s Cultural Surveillance once said, “Nobody goes to see films by Apichatpong. Thai people want to see comedy. We like a laugh.” While his films are structured too loosely to have a distinct moral or message, his intentions are clear.

“Cemetery of Splendour,” like many of Weerasethakul’s films, features touches of magical realism. In “Boonmee,” the magical elements were more exaggerated with many Thai folktales and superstitions of reincarnation, such as talking fish, creatures of the jungle, and more, incorporated into its narrative. Here, the magical realism and dream imagery is incorporated more subtly. Jenjira has a conversation with the two goddesses from her local temple, appearing as two beautiful but otherwise regular women. We see a distant memory of a creature in a lake, too far off to make out clearly. Perhaps the most striking and abstract element of magical realism comes three quarters of the way through the film, when a shot of the sky is interrupted by a massive amoeba that crawls across the lens.

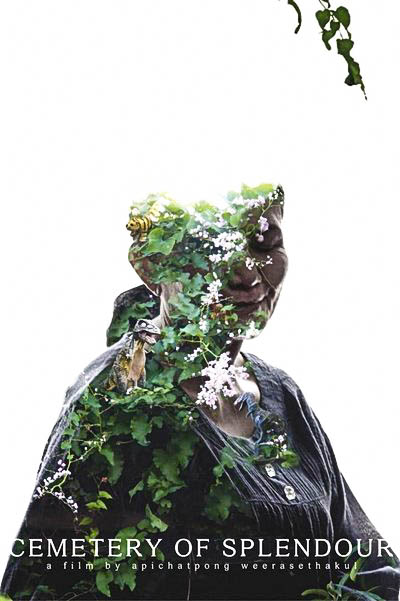

Other elements of the film, though not quite as magical, certainly match the strange, unpredictable logic of dreams. For example, the protagonist has one leg that is several inches shorter than the other. In one shot, people shuffle around on park benches for no apparent reason, and in another shot, statues of dinosaurs from a nearby theme park loom over a lake.

Perhaps the most notable of these dreamlike flourishes is the light machines at the hospital. The doctors can’t seem to find a cure for the soldier’s ailments, but have prescribed a unique form of treatment for the comatose men: light therapy. This appears in the form of L-shaped neon tubes over the men’s beds, which supposedly will give the men more pleasant dreams. The tubes bathe the hospital room with an eerie glow, slowly changing from one color to the next.

These light tubes serve as the visual centerpiece for the film. In one stunning sequence, an overhead shot of escalators in a mall fades over the course of several minutes to a shot of the neon tubes in the hospital room. Next we see that the town, somehow, became bathed in the light of the tubes. We see houses, streets, and men sleeping on sidewalks enveloped in the light as it slowly shifts from one color to the next.

The film does not have a progressive plot, but instead proceeds through a series of encounters. Progress comes in the form of the strengthened relationships between the main characters and the emotional awakening they experience through knowing each other. There is a sense of sorrow and tenderness in the friendship between Itt and Jenjira, as Itt’s inability to remain in the waking world and Jenjira’s inability to experience his dream world separates them. These worlds connect in a heartwarming scene where a sleeping Itt assumes Keng’s body and guides Jenjira around the great palace that once stood. The scene is shot from Jenjira’s side of the world, and where Itt describes towering halls and thrones of gold we see only forest and crumbling statues, and yet the descriptions are so vivid it is difficult not to be transported into the dream. The same could be said for the film as a whole.