Exley Science Center may have been the embodiment of 1970s architecture, but it also was an instance where the University severely mishandled their funds after gaining 400,000 shares of Xerox stock worth more than $56 million in May 1965. Adjusted for inflation, the value of the University’s Xerox stock would be worth $418,612,484 today. What is now the Exley Science Center cost $13 million upon its completion in 1971, which, while it may not seem like a lot compared to the University’s funds at the time, was originally estimated to only cost $5 million. The project represented a broader pattern of financial errors that came during the Edwin D. Ethrington administration, President Victor Butterfield’s successor.

Adjusted for inflation, Exley would have been more than $46 million over its estimated budget had it been constructed today. For the University in the late sixties and seventies, however, the boom the endowment received from Xerox stock seemed to be infinite. Historian David Potts dedicates an entire chapter to this phenomenon titled, “Hazards of New Fortune” in his book “Wesleyan University, 1910-1970: Academic Ambition and Middle-Class America.”

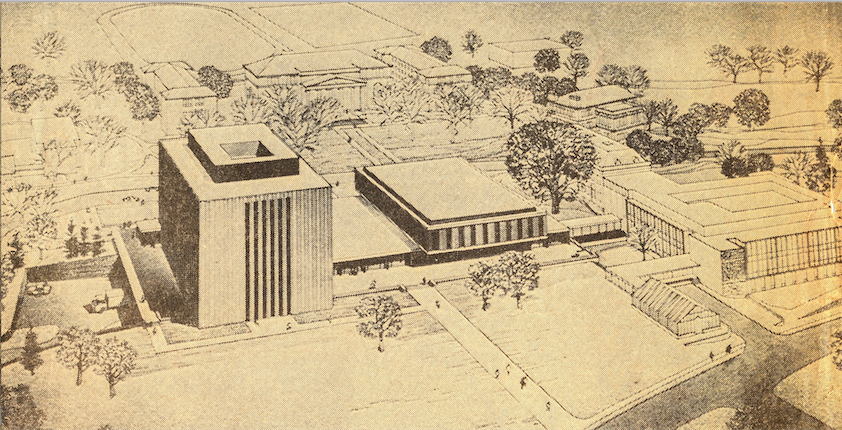

“With the endowment’s market value almost doubled overnight, from a level already comparable to those of Amherst and Williams, Wesleyan’s building program could now proceed in a brisk, ambitious fashion,” Potts writes. “The Lawn Avenue Residence Halls [now known as The Butterfield Dormitories, or “The Butts”], including commodious quarters for the College of Letters and the College of Social Studies, opened its first two units in 1965…. Construction of a three-unit science complex began in June 1965 and would give Wesleyan’s little university plans their first major asset.”

The vaulting ambition of the Butterfield administration was now manifesting itself in an even greater physical presence for the University. Throughout his book, Potts centers much of his work around the uniquely Wesleyan notion of the “little university,” an apparent oxymoron that alumni take pride in. It involves intimate contact with professors and also access to significant resources, small classes grappling with big ideas, and, by the seventies, a lot of money for a small school.

This ambition was manifested in Exley and Hall-Atwater. No small part of the manifestation of this ambition was in the modernist architecture of the Science Center, which makes spectators scratch their heads from the minute they go on a tour at Wesleyan. While the initial cost estimates were modest in relation to the endowment, the actual cost of construction of what is now Exley proved otherwise.

“Clothed in precast concrete panels with a brownstone aggregate surface, the library and tower would display decidedly modernist lines and scale,” Potts writes. “During the construction years, final costs for the new science facilities would escalate sharply beyond original calculations. The estimated $4 million for Hall-Atwater would rise to $5 million and the estimated $5 million for the library and tower [Science Library and Exley] would rise to $13 million.”

The same pattern was followed for the Center for the Arts (CFA), which was reduced in planning from fourteen buildings to eleven. Designed by Kevin Roche, a venerable architect who was informed by both classical and modern aesthetics, the CFA was marveled at during it’s construction by The New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable. She called the Stonehenge-esque arrangement of Indiana limestone structures a “subtle arrangement” of planes and masses that was “skillfully balanced,” creating artistic spaces that would “make larger universities green with envy.” Regardless of its merits, the CFA’s financial footprint grew eerily similar to that of the Science Center.

“Early planning estimates in 1965 and 1967 set the cost at $5 million,” Potts writes. “That figure would steadily swell, particularly from the groundbreaking in 1970 to the opening in 1973. The final cost would reach almost $13 million.”

These costs—along with a $4.2 million new central power plant to keep up with the rapidly growing campus, a $1.8 million hockey rink, and financial provisions for a new coaching position to bring the men’s hockey team from a club to varsity level sport in 1971—made the early 70s a time of seemingly never ending spending that ended up diminishing the endowment that was once boosted by Xerox.

The building projects represented just some of several ways that the school was trying to change and improve during this era. The “Vanguard Class” of African American students arrived in 1965, bringing with them a considerable degree of change to the University. This change brought about quick demographic and cultural changes to student life, and the University was far ahead of its rivals in experiencing these changes.

“The presence of African American students would increase from an average of two per entering class in the early sixties to an average of about thirty-seven from 1966 through 1969,” Potts writes. “Amherst and Williams would not begin to approach a comparable percentage level until the early seventies. By their senior year, the vanguard group and their successors would have the numbers and solidarity sufficient to press effectively for urgent attention to racial issues on campus.”

There has probably not been a greater time of change in the Unversity’s history then the late sixties and early seventies, where both the physical and demographic landscapes of the University transformed drastically. Although students still benefit from Exley and the CFA today, we would have far more resources available to us had we not recklessly spent out of our endowment during this time period. Schools like Williams, Amherst, Harvard, and Princeton have maintained high endowments while fundraising separately for capital projects.

The This Is Why campaign will have been one of the greatest periods of financial growth since the capital campaigns of the Butterfield Administration. Although much of our education here cannot be quantified into dollars and cents, it takes material resources to sustain our education and that of Wesleyan students to come. So the next time you and your friends make fun of a This Is Why advertisement, remember that we once had the highest endowment per student of any school in the country, and that we lost much of it with just a few poor financial decisions.

Leave a Reply