“Son of Saul” is not an easy film to watch. It can feel suffocating, even nauseating, while at other times unbearably tragic. The movie immerses the viewer in a storm of cruelty, sorrow, and inhumanity with a focus more singular than any in recent memory. And yet, it refrains from being indulgent and manages to find traces of beauty among the atrocities to which it bears witness.

The film follows Saul, a Sonderkommando, one of the Jews interned in Auschwitz charged with aiding in the disposal of bodies from the gas chambers under threat of death for noncompliance. Saul sees a boy who initially survives the chamber slowly die from the aftereffects of the poison. Saul then takes it upon himself to give the boy a proper burial in line with Jewish tradition, telling others that the boy is his son.

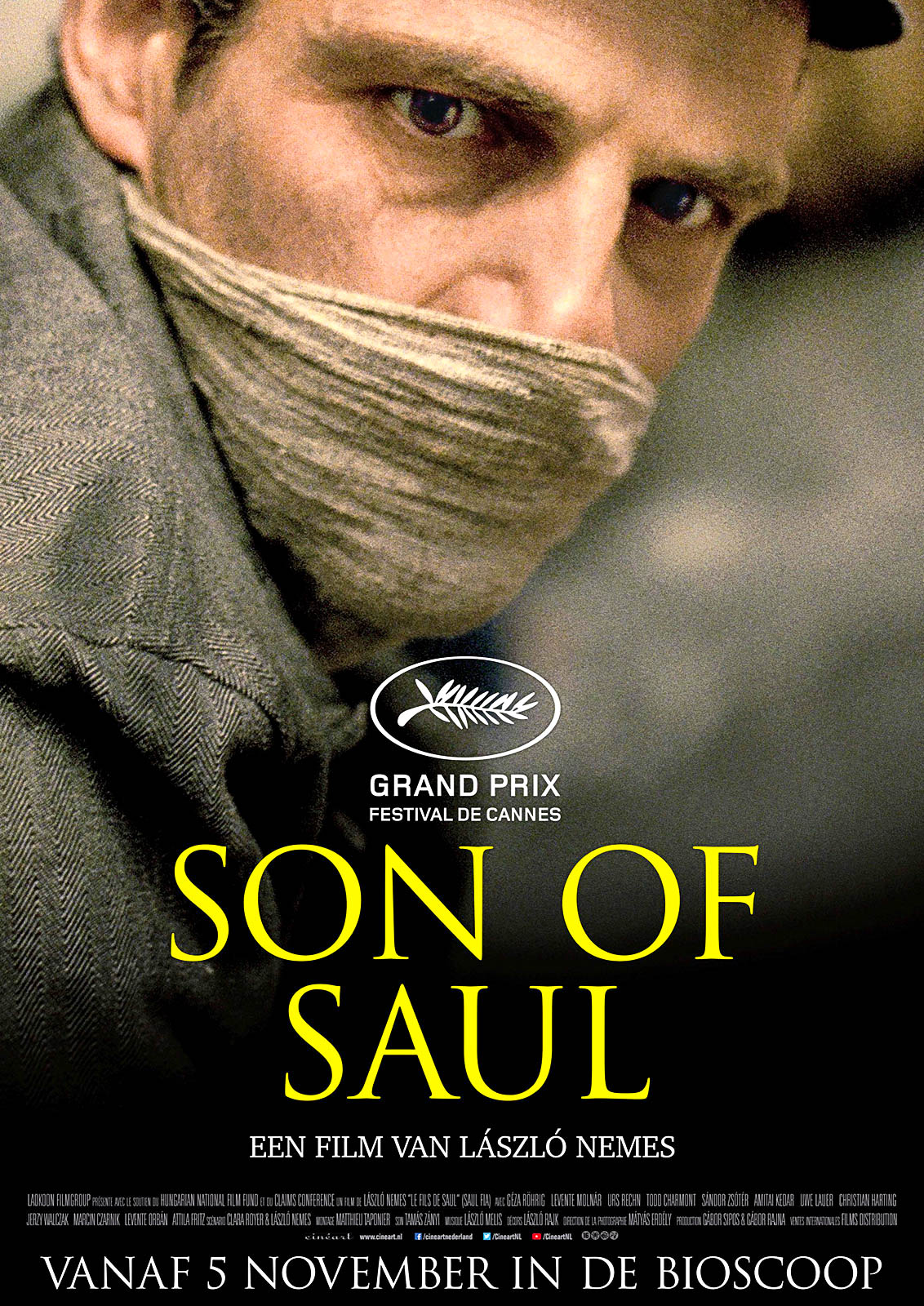

The film is, quite literally, centered on Saul. The camera remains in a close-up on Saul with shallow focus (where the background images are out of focus) for nearly the entire movie. Remarkably, László Némés is a first time director, though he acted as the great Hungarian auteur and master of the long-take Bela Tarr’s assistant for two years. The deftness and skill with which Némés directs is immensely impressive. His technical achievements alone are astonishing, but even more so in a film filled with such strong emotion and feeling. He is remarkably assured for a newcomer, unafraid to break from his stylistic patterns when it serves the story.

The effect of this highly limited focus is that we get only glimpses of the tragedy that surrounds Saul. The horror becomes almost peripheral, but its threat is constantly present, hovering around the edges and occasionally creeping in at times to show its hideous face front and center. The suggestion, however, is enough, and in many ways more powerful than showing the images of the Holocaust directly. But as a result of this tight focus, the film is often overwhelming. It feels as if our eyes are being pushed against the lens of a microscope and we are forced to fully share in this man’s experience, unable to look away or catch our breath.

This stylistic immediacy serves two main purposes. First, to show how numb these men have become to the death around them, merely doing what they need to move forward and get through their wretched task. Second, to avoid as much as possible the romanticization of such an unspeakable event, of which Hollywood and many Holocaust films have been accused.

The challenges of representing of the Holocaust are well documented. From Alain Resnais’s film “Night and Fog” and Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah” to Spielberg’s “Shindler’s List,” filmmakers have struggled with the weight of portraying the Holocaust in a responsible manner and have found wildly different ways to do so.

Early on, filmmakers and journalists were aware that the stories they were telling would largely define how the Holocaust would be remembered, and that eventually our memory of the events would shift until our vision of the Holocaust had moved away from the truth by unknown degrees. They wrestled with the burden of preserving its atrocities and the impossibility of total accuracy. “Son of Saul” is very aware of this problem and tackles its subject with nuance. Although it is troubling and difficult to call a film such as this beautiful, it is difficult to deny that “Son of Saul” possesses a certain aesthetic appeal despite the ugliness and brutality of its topic.

Yet for every dash of beauty and hope found in the story, there are fifty parts bleakness and savagery. Saul pursues his goal with a single-minded intensity at the expense of practical concerns, endangering the lives of those around him. He winds up caught up in a plot with the other Sonderkommandos, who have heard rumors that they are next for the gas chamber, to gather weaponry and explosives in a bid to escape the living hell they have found themselves in. Saul contributes to the effort, but seems to care very little about escape or helping those around him. His actions endanger the mission, and at a key point in the film, one of his fellow Kommandos says to him, “You value the dead over the living.” However, the film leaves it up to the viewer to interpret the morality of Saul’s choices. What are we to make of them? Is he justified in his quest? Moreover, is the narrative merely allegorical, and if so, what lies beneath?

Saul’s journey takes on a more universal significance when framed as an attempt to find meaning in the midst of unimaginable horror. His small act of tenderness in an extraordinarily brutal world feels like an act of rebellion not just against the Germans, but against the cruelty we visit upon each ourselves.

Overall, the film is a reaffirmation of life and an acknowledgement of the incomprehensibility of death that eschews easy answers in its existential discussion of human nature. “Son of Saul” may be hard to watch, but in many ways, it is essential to do so.