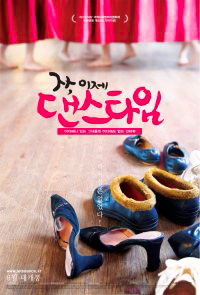

“Let’s Dance,” screened by the Korean Students Association (KSA) last Friday, April 1 follows Korean women who are tired of the shame and uncertainty surrounding abortion, and have decided to come forward and tell their stories. In South Korea, abortion is illegal. Many women with no other options are forced to find places where they can get secret and unsafe abortions.

The film opens with three women sitting on the floor, comparing how many abortions they have each had. They speak starkly and openly about their experiences in a surprising manner. They speak about how they had no other choice, and about how absolutely terrified they were. They compare horror stories about how they were completely exposed and tied to chairs, feeling out of it but still in pain because they weren’t given full anesthetic for their procedures. The women lapse into silence.

Filmmaker Jo Se-young uses a choppy, distorted, crackling television screen to transition to the next scene, shocking the viewer into paying closer attention. Each woman has a chance to tell her story, showing herself as a whole and complex person, and not allowing herself to be defined by the fact that she had an abortion. The scene switches from blurred face to blurred face, making it feel that it could be anyone’s story while simultaneously exposing how many women have had to suffer in silence.

“I wanted to talk about my experience with other people,” one woman stated after telling her story.

After she speaks, her face crystalizes and transitions into clarity. The camera flashes to each blurred woman, and each face changes from an anonymous haze into sharp clarity. Through showing themselves and their faces to the camera, they are saying that what they did was not wrong and that they should not have to hide any longer.

The women speak on various topics, but they overlap in disturbing and problematic ways. Many of the women seemed like they were coerced into sex by their significant others, who tried to convince them that they weren’t going to get pregnant if they had sex without a condom just this one time. Sex seems to be surrounded by a convoluted web of guilt and anxiety for women.

“One of the most jarring scenes in the movie was that the women were coerced into sex,” said Janet Shin ’18. “They were under the impression they would just be holding hands. I don’t know how to reconcile that. However, I do not want to impose my American perspective onto their experiences because I feel that that would be misguided.”

Women are pressured into being mothers by the society that surrounds them. The film shows a campaign by the Welfare Ministry to encourage women to have children by having spaces for them to relax with soothing music and foot massages. In Korea, when a baby is born, it is already considered to be one year-old. Since the common understanding in Korea is that the beginning of life is at conception, it can make the process of abortion shameful and full of guilt.

“It’s very intense to witness how so many Korean women have to carry the burden and responsibility of their own abortions,” said Shirley Fang ’18. “Their inner turmoil to make the right decision for themselves and, at the same time please society, just breaks my heart.”

One woman tells the camera about how when she was younger, her school made her watch birth and abortion videos. They were so awful she felt sick for days. After she watched the videos, they made her take a chastity candy which symbolized her promise to remain a virgin until marriage. This institutionalized process speaks to the culture of fear that surrounds the entire realm of sex, abortion, and pregnancy.

“To me, the film captured the essence of the widespread nature of the issue at hand, and also captured the way in which there is no one party to blame in Korea, government, men, doctors, etc., but rather a systematic failure on many different sides,” said Emma Johnson ’19. “One of the most striking elements was the lack of sex education, particularly among the men but even the women, though I don’t perceive that as a strictly ‘Korean’ problem but is in fact widespread around the world.”

Although the documentary does speak a little about the laws and legal processes that surround issues of abortion, it mainly focuses on the stories of the women. It lacks a political agenda and brings the issue into the concrete world rather than the hypothetical and abstract moral debates that usually surround abortion. It showcases the lives of normal women who lived through a horrible experience and want to share their stories.

“I want to acknowledge what happened and love the old me,” one woman said in the film, with tears running down her face. “That’s what made me want to do this interview.”

4/8-This article has been updated to clarify that the common notion in Korea that life begins at conception is separate from Korean culture. The original article stated, “Korean culture makes no secret of when it defines the beginning of life.”

4/24-This article has been updated to expand the first quotation of Janet Shin ’18 to provide context, adding a sentence about an “American perspective.”

Leave a Reply