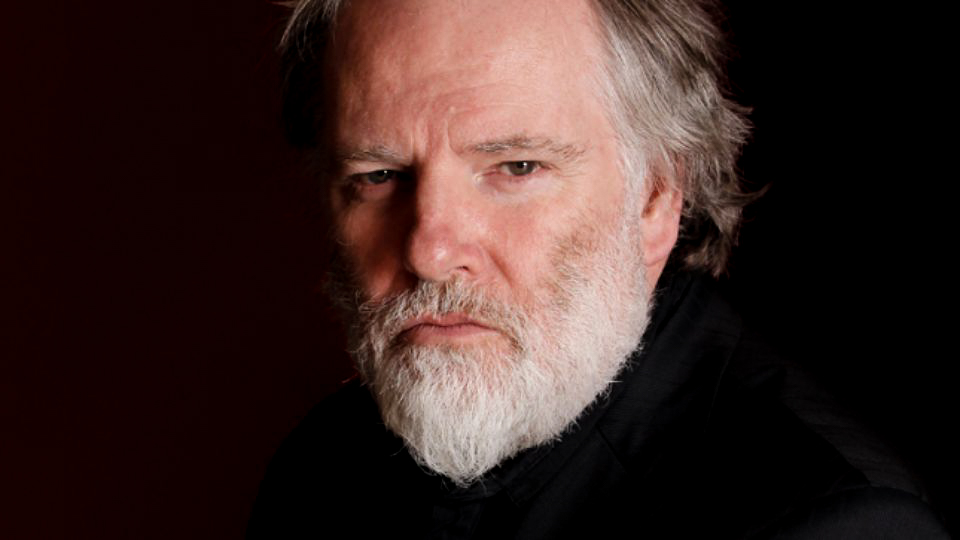

c/o avclub.com

Guy Maddin’s most recent cinematic psychosexual secretion is the deliriously entertaining “THE FORBIDDEN ROOM,” which screened at the Film Center this past semester. The project began as a series of adaptations of “lost” silent films—works that have been destroyed or lost to history, existing only as a title or a fragment of synopses.

Maddin grew up in Winnipeg, and from the tender, young age of 20, drew upon the combination of broodily pent-up family history and the forgotten pockets of silent and early sound cinema to produce darkly funny yet heartbreaking melodramas. Over time, his style has broadened and become more inclusive, taking on a wider range of artistic choices with regard to genre, performance, and subject matter. Having exported his pining, pawky, and pervy sensibilities out of Canada and across the globe, Maddin now teaches at Harvard University, and agreed to talk more about “THE FORBIDDEN ROOM” with The Argus over e-mail.

The Argus: “THE FORBIDDEN ROOM” is simultaneously very intellectually dense, with its baroque structure and narrative, and riotously silly and entertaining. How did the structure of the piece come about? Were you aware of this dichotomy while working on it?

Guy Maddin: When Evan Johnson, Bob Kotyk and I were writing the script, or, more accurately, scripts, for this project…we wanted to make sure each lost story was adapted with as much clarity as possible, because we knew they’d end up existing in endless combinations by the time viewers were let at them online as part of the material uploaded to our Seances interactive project. They not only needed to be clear, they needed to pay dreamy tribute to the idea of lost film, somehow, and we were especially proud of what we planned as the largest possible brow range in the humour department. Sure, we wanted some highbrow gags—who doesn’t, but we love our low brow crap too, and everything in between, if it amuses us. In fact, we don’t even know where our brows are at these days. My face is one big brow—one sitting fairly high on my tall forehead and another hanging pretty low, like a Robert Bork beard, and then a lot of matted hair in between. Us three writers got to looking like werewolves in the writers’ room, what with our stupid brows flourishing everywhere.

The structure of each story segment—there are 17 fragments of lost film adaptations in our feature—is compelling enough, with three acts, protagonist, antagonist, third act trouble, all that stuff from how-to-write-a-screenplay texts, but when we stuck them together into a feature, as we had to do in order to access the much larger feature film funds available from the state in Canada (internet interactive projects can access money, but only much smaller amounts) we knew we’d have to resort to something radical. We briefly considered making a documentary about lost film, but the very notion of that sent us swooning into long long depressive naps. All three of us had long been fans of John Ashbery’s favourite writer, the great French enigma Raymond Roussel. Roussel was a contemporary of that first wave of Surrealists, but was not interested in joining them. For one thing, he didn’t seem interested in the subconscious or in dreams in that Surrealist way. He had his own reasons for working the way he did, and no one quite ever divined those reasons. The way he worked? Well, in his long poem, “New Impressions of Africa,” he would start in at the beginning, like any other poet might, then quickly detour into a parenthetical aside, then within that first bracket, quickly detour into another parenthetical aside, one aside after another, until very many asides or detours or narrative levels had been introduced and then denied completion in this parenthetical way, until Roussel wrote his way into the very centre of the poem—some 80 pages long, I think?—and then slowly closed each parenthesis by finishing the long-forgotten line of the poem, written many pages earlier, closing all the ideas within all the parentheses—slam! Slam! Slam! Like so many doors!—Until the poem’s end, so that the reader can read the work from start to finish, or from beginning and end simultaneously, working his or her way toward the middle, or from the middle outward to the start and the finish.

Roussel uses this structure in our favourite work of his, “Documents to serve as an Outline,” a dense, gorgeously precise and puzzling prose piece involving many narratives nested within each other, Russian doll-style. No sooner are a few characters introduced and given a sentence or at most a paragraph, than Roussel is distracted by stories involving characters tangential to these, and we the readers are plunged, through these trapdoors of digression, into a lower depth, or inner concentricity, of narrative, and every ring of the Rousselian tree cross-section is a gorgeously crafted thing, and there is much pleasure in the precision and beauty for its own sake, and more in getting lost in the levels, and the most pleasure of all in pulling out from these delirious nestings and finding your bearings, remembering your depths. For us, the pleasure of making “THE FORBIDDEN ROOM,” and in watching it, lies in this pulling out. The movie has a basic three-act structure, with six narrative layers in the first act, then nine in the second, another nine in the third, then the sudden climaxing of all the stories and a whole lot more. Simplement! The trouble is, by the 100-minute mark there are still new stories starting up and the movie gives no indication of its intention to end, ever. Thankfully it does end, but this strange shape makes the 119-minute running time seem much more like 123 minutes, which is too bad, because it’s mostly a brisk affair.

All three of us are also enormous fans of “Mission Impossible IV: Ghost Protocol,” and its director, Brad Bird. Man, that thing rolls! And it’s much longer than our film. Yes, it has giant sandstorm set-pieces and scary fights on the glass exteriors of high rises, but we have some pretty woolly stuff ourselves. I think the two can be compared in spirit, except maybe the part where “Mission Impossible” is a Scientology allegory and our film is slightly more secular. I wish “Mission Impossible V” were as good.

The writing process was simple. We looked up all we could about…any lost film that interested us. We usually found next to nothing – just a poster, a one-sentence synopsis. Most bloodhounds have more of a sniff in their nostrils. So we sniff the air surrounding each title, almost paranormally, to get a hunch—often nothing more—of what the lost movie might have been about. Then we plugged that hunch into the 1927 screenwriting flow chart in book form, PLOTTO [An early screenwriting guide]—a magnificent aid. Ashbery once told me he used PLOTTO to write a poem. Well, we used it to write our scripts. I had a first edition of the book, and consulting it felt like flipping through the Dead Sea Scrolls. It’s amazing, and the goose bumps rose like golf balls upon our backs as the stories took shape. Sometimes our sweaters would fit us so lumpily at the end of the workday, so excited we were. We’d rub down each other’s back until it was smooth enough for us to present ourselves to loved ones back home.

A: It’s hard to keep track of the rush of imagery and fluxing color on the screen—how did the film’s style, which is rooted in ideas from early silent cinema but feels distinctly contemporary, come about? How do you feel “THE FORBIDDEN ROOM” stands in relation to your earlier work, in terms of shooting and cutting?

GM: I felt I was long overdue for a return to colour, since I had done nothing but monochrome work since 1992. I think I tried working in colour a few times recently but the lab kept sending me [black-and-white] stock anyway, or, if I did manage to shoot in colour the labs would catch my “mistake” and “correct” it for me by printing my colour footage on [black-and-white] stock. Anyway, this time we went digital and shot in raw colour. By the time Evan and his brother Galen got around to timing the video images we knew we had a feature to make. We wanted 17 different palettes for the movie, one for each movie within the movie. We started with a tribute to early Hollywood 2-strip Technicolor, where all skins, regardless of race, are more or less apricot, and everything else is aquamarine. The we used British and Soviet 2-strip palettes, which are different because those countries used different chemicals in their colour film stocks. That left us with 14 more palettes to go. That’s when Galen and Evan went rogue on chemistry, pretending the periodic table had many more elements, and much better ones for photographic baths, than it really does. We developed the attitude of housepaint companies, who create thousands of shades and as many evocative names for their chipbooks, in naming our own on-screen hues. Some combinations we used are as gorgeous and delicate as possible, like Moss Manse & Ruskin’s Thigh, which are extremely striking and pleasing together. My favourite happens to be Eisenhower White and Rock Hudson’s Nipple, this latter a truly delicate dusty rose. Soon we allowed third, fourth and even fifth colours into our palettes. We studied a lot of Douglas Sirk, who came from a painting background and whose colour films are incredibly expressionistic and exciting. All of this paintchip book’s wealth of variety was achieved in post.

The cutting was simply determined by the usual inner rhythms of each sequence. Our editor John Gurdebeke worked his ass off to get this movie of a million cuts done, but once he found the one and only rhythm and pace for the picture it was just a matter of his Herculean effort. I’m really proud of how it turned out and I think it’s the best conceived, shot, and edited film of ours – maybe only “Cowards Bend the Knee” comes close.

A: How did the mid-film “Final Derriere” sequence come about, with the music by Sparks and the performance by the man with the blanked- out face?

GM: Evan decided this lost Greek film, “Fist of a Cripple” (1931), needed to be condensed from its 20-minute running time, so we shot it down to a three-minute musical number for the feature. None of us on the team is a songwriter. Galen makes all our music by cutting up found public domain source matter and boiling it down into a stew or spread for our scores, but he doesn’t know how to write a song. So I asked my good friends, the brothers Ron and Russell Mael, if they would write something for us. We thought maybe we’d have someone else perform what they wrote, but within a few hours they sent us the finished song, freshly written just for us. The way it cuts together is more music video than musical number, but that’s going to happen if you decide to turn a narrative into a musical after you shoot it.

We decided to use the original Russell Mael vocal, but couldn’t afford to have Russell, who was two time zones away, shot for the sequence, so I shot my friend Darcy Fehr and Evan blobbed his face out until he looked exactly like Russell Mael, had Russell’s face been blobbed out. Simplement!

A: To bounce back in time, your first film, “Tales From the Gimli Hospital,” from 1988, is black and white and shot on 16 mm. I think first films are really interesting because, as the filmmakers’ options are so drastically curtailed, what ends up on screen tends to be this tangled core of what’s most important to them. What was the genesis of “Tales from the Gimli Hospital,” and how do you feel about the film now?

GM: I had such a great time shooting “Gimli,” but that was so long ago, and my obsessions were so occult. I believed nirvana could be found in a scratchy blanket of audio crackle, that the real frissons of cinema lay in the murky or even milky grey shadows supposed to pass for black, that intoxication came from scratches, bubbles and mildews in the emulsions, and that mannered and mythic tableau-like posturing verging on absolute stillness, except horizontally held stillness, supine actors in bed preferably, offered the great highs of all. I remember liking the atmosphere and feel of that movie, which translated for me a mundane and palpable history of the real Gimli into something richly mythic. It turned Gimli into a place I liked to look at. That’s all I remember. The rest is forgotten.

A: As of this moment, which painters, writers, filmmakers are most interesting to you? Is there something new or old you’ve recently discovered?

GM: I love Pere Portabella’s “Vampir Cuadecuc” (1971). It’s a documentary on the making of Jess Franco’s “Count Dracula” (1970). It’s such a revolutionary reinvention of the documentary, it makes me want to make essay films for the rest of my life. For that reason I also love Miguel Gomes, he really knows how to make a hybrid. And Ed Wood, who seems to have been fearless. I don’t care how afraid he was, his “Glen or Glenda” is the most original film of the 20th century.

A: Could you talk a bit about your relationship to myth and melodrama, and their importance in your work?

GM: Melodrama is the truth uninhibited. We all think of melodrama as something “over the top,” something grotesque, hammy and exaggerated, something no one with good taste could enjoy. But good melodrama can be great art. If the truth were exaggerated it would no longer be the truth, it would be a distortion of the truth. But good melodrama disinhibits the truth, allows it to show, allows repressed lusts, hatreds and murderous impulses to manifest themselves, revealing the secrets of each character, tying them together in plot coincidences that make for a tidy running time without distorting the honesty of any depicted relationships. That’s exciting to me.

Myths are the feelings I have whenever I default to my earliest models of the way the world works. As a child I built simple models of the world. I was revising them always because I realized I had constructed erroneous impressions and understandings, and almost every day, then as I aged, less and less often, I built on the ruins of these old discarded models my new models, until now, finally, as an adult, I find myself standing upon the spongy ruins of a thousand discarded models, as if I were a totem pole balanced upon a great mound of raked leaves. In times of stress, my feet search for security, and find only the crumbs of my very first impressions are at the base of any hope of standing upright. I fall down, of course. Those are my myths.

A: Could you talk a bit about the “Seances” project, and about your next undertaking?

GM: “Seances” is launching at the Tribeca Film Festival in April. Then it goes live online. It will enable anyone online to hold séances with lost cinema! We’ve uploaded a shitload of our lost movie adaptations into the interactive wireframe. It is my humble but desperate hope this interactive will redefine the way we think of cinema’s past and future! It should be just as reverential to filmic emulsions as “The Forbidden Room,” which is really just a two-hour trailer for “Seances,” but far more digitally addled, cockeyed. I hope it’s insane and elucidating. My favourite aspect of the séances project is that every time someone visits our interactive the site will produce a unique movie out of the material we created out of lost matter, and that once that unique film is screened once, for just one viewer, that film will be destroyed and never seen again. To be sure, the films will be collisions of randomly generated non sequiturs, but we have set it up so the chances are good – not 100% guaranteed, but good – that the viewing experience will be good, and sometimes great. But no matter how good or bad, that film will be destroyed. I want people to be amazed by the randomly produced greatness of a viewing experience, then experience a strong sense of loss in the knowledge that [the] viewing experience can never be had again. It’s time the Internet started losing things.