c/o slate.com

Murphy’s Law tells us that anything that can go wrong will. In reality, the so-called law is nonsense, a lousy epigram at best; Murphy’s Law assumes that objects outside of our control can react accordingly to our own fears about a situation, which is, of course, impossible. But in fiction, anything is possible. And in Hanya Yanagihara’s “A Little Life,” Murphy’s Law seems to be alive and well, especially in the case of its protagonist. Everything always seems slanted downhill, bound for failure no matter the circumstances. Even in its brightest moments, “A Little Life” assures the reader that doom is the endpoint—that in the end, it will all go badly—which, in my swath of gloomy books, made for one of the most depressing yet predictable stories I’ve read in recent time.

Contrary to the title, “A Little Life” has quite a lot of life—814 pages of it, in fact, split unevenly between four characters: Malcolm, JB, Willem, and Jude. The novel opens with this quartet in their 20s, all living in New York City after living together in college. In one of their first scenes as a group, we get a quick portrait of the members: Malcolm, the simple but sweet naif, a budding architect and craftsman; JB, the self-righteous and energetic artist, bound for fame and probably drug addiction; Willem, the pure man from Montana who wants nothing but happiness and an acting career; and finally, Jude, the parentless, almost impossibly brilliant law student who is plagued by his dark past, which he shuts away from his friends for most of the book.

At first, these characters meet together weekly, keeping their bond tight despite the growing obligations of adult life. As the quartet grows up, however, Malcolm and JB soon fade out to other NYC circles, which is unfortunate for a couple of reasons: first, that JB does actually become an artist-turned-drug-addict, though Yanagihara only chooses to chronicle one episode of his addiction before he gets treatment and quickly gets better; and second, the depiction of Malcolm and JB’s blackness, which includes such clever and thoughtful commentary as, “‘How’s life on the black planet?’ Willem asked JB now. ‘Black,’ said JB,” all of which wholly drops off in the second part of the novel. It is as though Yanagihara starts a discussion only to stop talking mid-conversation. This leaves us with Willem and Jude, but way more of Jude. These are the only two characters who stay friends well into their 40s as both of them become increasingly successful, Willem as an actor and Jude as a lawyer. In the end, after many years of turmoil, Willem and Jude end up together in a relationship, bound for what JB calls “lesbiandom”: For the last 200 pages, we follow Willem and Jude as they travel, cook, and pillow-talk, adding a dimension of love to their already intimate friendship.

As these characters move into the future, Yanagihara slowly reveals Jude’s past. The Murphy’s Law logic of the book solidifies in these episodes, where Jude’s childhood experiences worsen over time, from his early days in a monastery to his teenage years in a foster home. Yanagihara makes everything go wrong for Jude, both physically and mentally, and his early experiences begin to reflect those in his adult life—it begins, in a sick way, to make sense that Jude has a sadistic boyfriend before he enters a relationship with Willem, or that Jude’s self-harm steadily increases over the course of the majority of the book. In other words, the book is predictable, both in its smaller episodes and in its final conclusion, which I won’t reveal here, but should be clear for any attentive reader after the first 100 pages.

Coupled with its predictability is the sheer length of “A Little Life,” which is one of the longest books to come out in 2015, at over 800 pages. Many scenes seem to repeat with the same message, and the book could’ve been edited down quite a bit. I can’t count the number of times that Jude simply says “I’m sorry,” nor the number of times that someone confronts Jude about his secretiveness about his past. Because of its length, too, Yanagihara seems to have trouble with changing how certain characters think about both the world and themselves over time. Jude employs what the author calls “the logic of the sick,” a logic filled with self-doubt and blame that is thoroughly explored throughout the book. This logic never seems to waver in Yanagihara’s story, even though Yanagihara herself may want it to.

For example, in a flashback to his time at the foster home, Jude “had his first tantrum in years, and although the punishment here was the same, more or less, as it had been at the monastery, the release, the sense of flight it had once given him, was not: Now he was someone who knew better, whose screams would change nothing, and all his shouting did was bring him back to himself, so that everything, every hurt, every insult, felt sharper and brighter and stickier and more resonant than ever before.”

So what is it that actually changed in Jude’s mind? Is it that he simply got older? Yanagihara seems to think that the more words the better, and the more new imagery the better, as if these two will show how a character changes over time. In truth, Jude’s logic doesn’t change for most of the book; he is always self-loathing, and always blaming himself for the situations that befall him. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with the logic itself—it is symbolic of cyclical self-abuse, of the never-ending torment that trauma forces on its victim. What’s wrong is that Yanagihara tries to make it feel different over the course of the novel, putting the author and her characters in an awkward battle over stagnancy and change.

The most difficult aspect of this novel is not how Jude thinks about himself, but what happens to Jude. Jude’s sexual abuse and self-harm as a young boy is a tough read to get through, but again, after 800 pages of multiple episodes, even these traumatic and powerful subjects can feel contrived. In the end, many of Jude’s experiences of abuse—in their gratuitous repetition and, unfortunately, their desensitization—can only refer to themselves; each episode is so pronounced and so vividly explained that any sort of larger message on the human condition is cancelled out by the episode’s own detail. The most difficult scenes in this book are sort of like the most difficult scenes in a Tarantino movie, where you know for a fact that it’s going to be extremely and humiliatingly violent but you just have to get through it. Yanagihara’s slow reveal of Jude’s past, coupled with, again, Jude’s unfortunate luck in general, makes the reading experience even more grueling, as you always know that something terrible is coming, something that you cannot look forward to.

Some massive novels make up for their lack of editing with strong prose. “Infinite Jest,” for example, could’ve used a harsher editor, but it often doesn’t matter what the content of certain sentences is—you can just enjoy them for how they’re written, how they sound. “A Little Life” does not fall into this category, unfortunately. Yanagihara loves tacking on modifiers and coming up with far-fetched metaphors for the various demons inside Jude’s head, switching from coyotes to snakes to eels; I shouldn’t even mention when she describes the impact of a remembered memory as a “meaty, powerful smack.” The author is always searching for new ways to describe raw, human emotion, but often falls short of her target. The result is prose that desperately wants to shock and sadden, but often just ends up just leaving readers with a bad taste in their mouths.

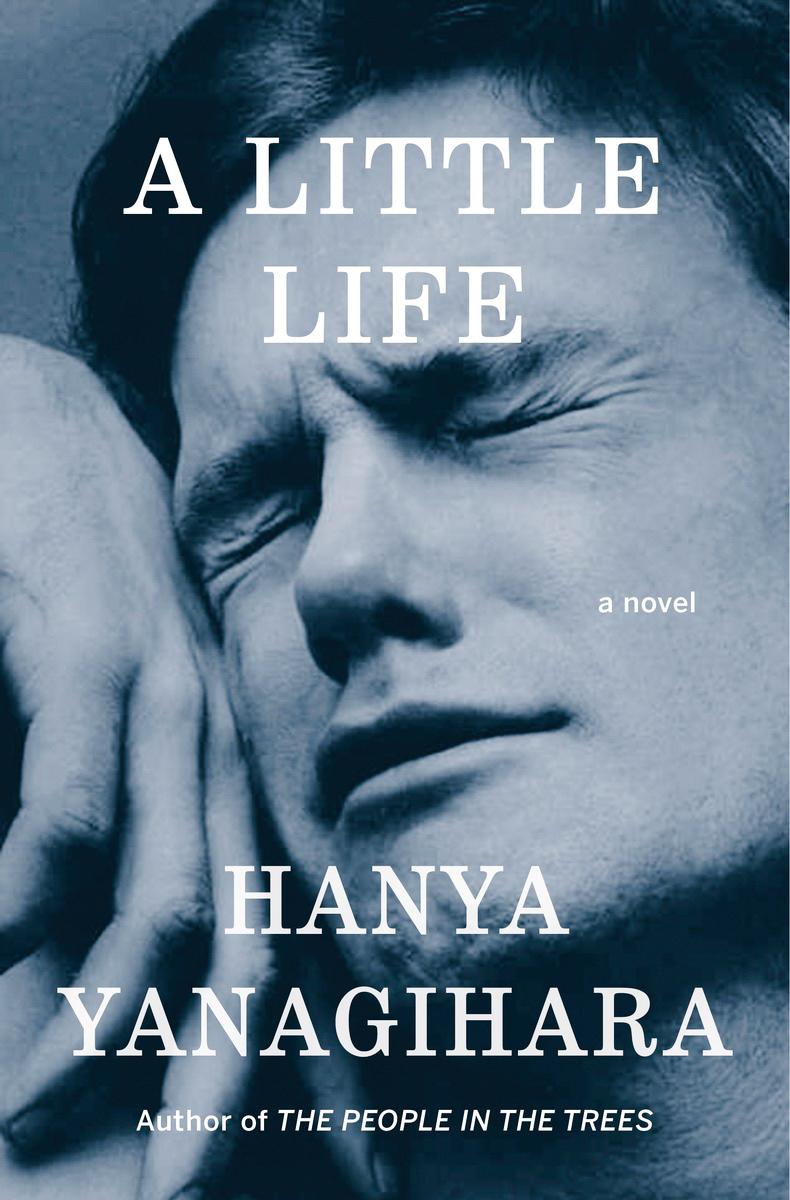

“A Little Life” won the Kirkus Prize, came close to winning the Man Booker, and was listed as one of the best books of the year by almost every major newspaper and journal in the United States. An obvious question then, is why this book has become so popular despite all my reservations. Is it that the cover is so appealing, with its weeping man and large block lettering? Or that people just tend to like huge books? A possible answer may come from how I’ve heard friends talk about this book, a novel that they felt “depressed” or “traumatized.” Besides the fact that it’s puzzling to say that you were traumatized by a book when that book’s main character has gone through more trauma than most, it is revealing to see how “A Little Life” readers explain their experience, as if they had just endured trauma themselves.

People seem to see Yanagihara’s novel as something to endure and fall victim to, as if the novel itself were an agonizing experience that they have successfully come out of after 800 pages. In truth, I don’t feel especially strong about this attitude in any which way – I mostly just don’t get it. If a reader acts as if they fell victim to a novel, then that assumes they had no agency in actually picking up the book and getting through it, which is just silly. The hype of “A Little Life,” if not just among my own friends and the few other reviews I’ve read, seems to come from some bizarre place in readers’ minds where victimization means validation and agency is considered passé. I didn’t feel victim to anything in Yanagihara’s novel, besides, perhaps, some clunky sentences and overwritten passages. But again, I was the one who chose to pick it up.

1 Comment

Cat lover

Your disdain for this novel perplexes me. It was not predictable. The predictable ending would have been Jude finally finding peace and overcoming his past.