Israeli-Palestinian writer Sayed Kashua initially planned to spend a year teaching Hebrew at the University of Illinois before returning to his apartment in Ramat Denya, a Jewish neighborhood in western Jerusalem. But on June 12, 2014, a few Palestinian men kidnapped, and later killed, three Israeli teenagers near an Israeli settlement. About two weeks later, three Israeli teenagers burned a Palestinian teenager to death. Kashua read comments from readers who threatened to break his legs and kidnap his children. His daughter, according to a profile of Kashua in The New Yorker, was attacked with water bottles for being Arab.

And so, in July, Kashua announced that his departure was no longer going to be temporary; instead, he was leaving the country for good.

“Twenty-five years of writing and knowing bitter criticisms from both sides, but last week I gave up,” he wrote in his weekly column for the left-leaning Israeli newspaper Haaretz. “Last week something inside me broke. When Jewish youth parade through the city shouting ‘Death to Arabs’ and attack Arabs only because they are Arabs, I understood that I lost my little war.”

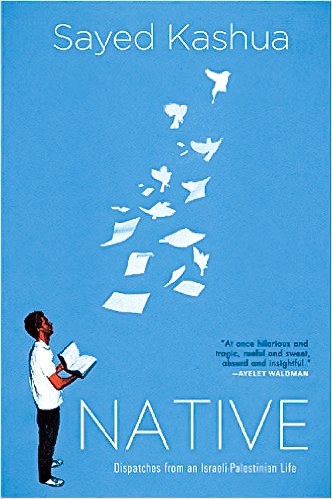

Kashua’s latest book, “Native: Dispatches from an Israeli-Palestinian Life,” is a collection of ten years of columns Kashua wrote for Haaretz. The stories are organized chronologically, from a letter to the editor Kashua’s wife wrote complaining about the factual accuracy of one of his columns to the last piece he wrote while living in Israel.

At their core, the columns are personal stories about Kashua, his wife, and their children. But barely beneath the surface, Kashua shows political motives. His stories reveal the bigotry around him and present to his Jewish audiences a depiction of an Arab world that is human and believable.

Kashua presents pictures of Palestinian life and Israeli bigotry to a largely Jewish audience. For over ten years, he has written a weekly column in Haaretz in Hebrew, his second language. In 2005, he created a show called “Arab Labor” that played on Channel 2, the most widely viewed channel in Israel, about an Arab journalist who writes for a Hebrew newspaper.

The columns in “Native” are frequently humorous, as Kashua writes of the absurdity of living life as a Palestinian in Israel. In “Holy Work,” he writes that he invited a Jewish housemaid to clean his apartment in order to relieve him of work. But, to his wife’s consternation, he took down any photos, books, or food that might reveal them to be Arab. When he finished, the walls were empty.

“That’s that,” he said. “This is what a Jewish home looks like.”

Kashua’s story is one of assimilation, and often other Arabs state their belief that he is abandoning his roots. He moves from an Arab neighborhood in eastern Jerusalem to a Jewish neighborhood in western Jerusalem. In “Pride and Prejudice” he tries to show his kids that he can rebel by playing a CD with Arabic songs to a security guard. But, he finds, there are no Arabic CDs in his entire car.

“I searched the pockets in the door and even in the trunk,” he wrote. “I couldn’t look my kids in the eye when I came up empty.”

Besides the tales of cultural abandonment, Kashua writes about the blatant racism that surrounds him in his Jewish neighborhood. Parents don’t allow their children to play with Kashua’s daughter. Fans at the end of a soccer game dance victoriously and cheer, “Death to Arabs.”

At least at the beginning, Kashua lends these scenes an air of hope. The people in his columns are generally good. Jewish friends and acquaintances react in horror when they discover some of the racism he faces.

But by the end—as the war gears back up in the summer of 2014—that hope seems to fade. In his final column from Israel, Kashua’s optimism has disappeared. An Arab citizen who desperately tried to assimilate into his own country through activities such as reading and writing in Hebrew, living in a Jewish neighborhood in Jerusalem, and hiding his CDs, his books, and his accent from unknowing spectators, Kashua is still not accepted by Palestinians or Israelis.

Many of these battles have stuck with Kashua even now that he lives in the United States. Less than four months after he arrived in Illinois, Phyllis M. Wise, then the chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, withdrew an offer of employment to a tenured professor, Steven Salaita, who had written a series of tweets that were critical of the Israeli government. Kashua, in response to Wise’s decision, wrote a column in Haaretz comparing the academic environment in Israel to the one in the United States.

“Again, just as in Israel, I find myself among Jews and Arabs,” he wrote. “And even though I’ve only been working at the university a short time, I have already learned that the battles in American academia about the Israeli-Palestinian arena are as fierce as the ones back home.”

But even as he holds, in America, many of the characteristics and battles he writes about in “Native,” he has left behind his hope. In “Native,” that hope is still inside Kashua—a remnant of a time when he could still hope for peace between Israel and Palestine—when, perhaps, peace was even a reasonable thing to hope for.

Leave a Reply