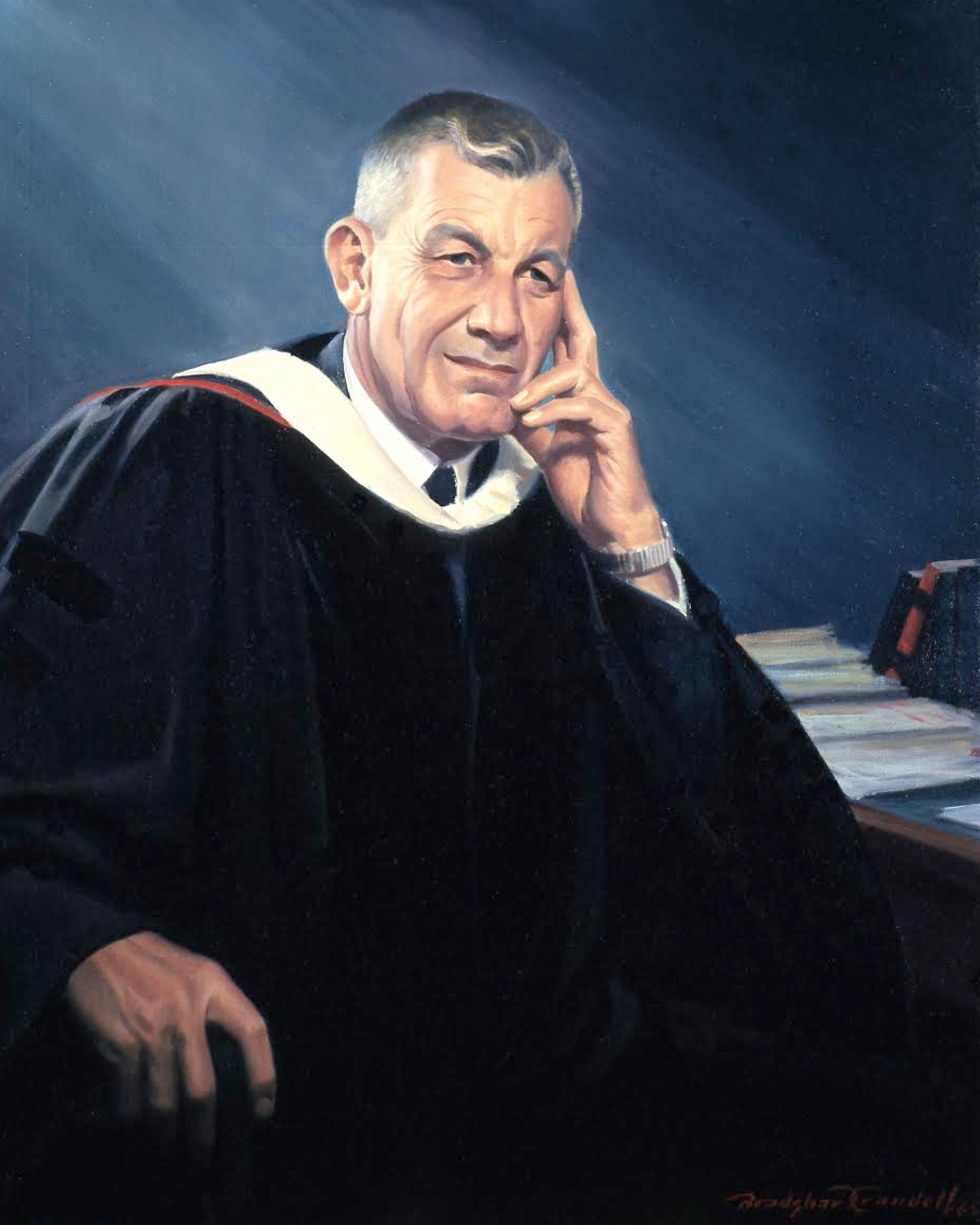

Known by most University students for the unfortunate shortening of the dormitory complex bearing his name (The Butts), President Victor Butterfield was Wesleyan’s longest serving and most influential president. If you see a building on campus today that is not North College, South College, Clark, Olin, or Usdan, it was most likely built or planned under Butterfield’s tenure as president, spanning from 1943 to 1967.

Saving Wesleyan from the brink of bankruptcy during World War II, Butterfield’s greatest work came in the post-war years, where he bolstered Wesleyan’s prestige with the addition of top-notch faculty from venerable institutions such as Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, and Princeton and quadrupled the school’s endowment in a little over a decade. A look into Olin Library’s Archives and Special Collections reveals a treasure trove of information surrounding Butterfield’s legacy. Perhaps the best point of departure is Butterfield’s 1955 annual report to the Board of Trustees, where Wesleyan’s progress under his guidance appears in his beautifully flowing prose.

President Butterfield’s report begins with a focus on Wesleyan’s growth in the post-war decade. Over the course of this decade, the permanent funds of the university doubled thanks to the generosity of many donors and the handsome bequest of George W. Davison, Class of 1892. Butterfield’s administration also boasted over 90 full-time faculty members compared to only about seventy for a student body that had not increased substantially in size. In addition, Wesleyan was investing $2,000 more than the cost of tuition in each student by the time of Butterfield’s address in 1956. At the time, tuition was $650, which translates to about $5,748 today given inflation. Therefore, Wesleyan’s $2,650 investment in its students back then would be about $23,436 today.

President Butterfield was keenly aware of his legacy, and in his writings he consistently posited the existence of a dualism between the free inquiry that takes place on campus coupled with the financial resources required that allow the former to flourish. In a letter to donors of the Alumni Fund late in his administration, Butterfield found that both free inquiry and financial stability are tied to tradition, writing, “[A]ll our current experimentation and innovation and all our hopes and dreams for the future are bound by our inheritance. We are evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Each generation receives, embraces and passes on the essence of the College’s life—its attitudes, its spirit, and its values. Tradition thus persists like the roots of a beech tree sprouting new trunks and branches, each with its own distinctive size and shape, but each with the essential qualities of the parent tree.”

Wesleyan historian David B. Potts dedicates significant space in his book “Wesleyan University, 1910-1970: Academic Ambition and Middle Class America” to President Butterfield, including the development of the campus under his administration. Starting in the 1950s, Butterfield began to pursue efforts to elevate the University’s facilities to attract the high caliber faculty that he had become known for. Butterfield partnered with prominent landscape architect Michael Rapuano, of the prominent New York City firm Clarke & Rapuano, who had been a classmate of Butterfield’s at Cornell where they were roommates and played together on the football team. From 1951 to 1967, Wesleyan retained Rapuano’s services not only for the college grounds, but also, as Potts clarifies, for advice on “architectural matters and on general plans for the buildings program.” His first project was landscaping for the now legendary Davison Art Center grounds.

More building was to come. But first, a capital campaign needed to be launched in order to secure the funds for greater improvements to the campus. This fundraising was an uphill battle for Butterfield, who was launching the University’s first capital campaign since the Centennial Fund was conducted between 1927 and 1931. On Butterfield’s first capital campaign, Potts writes, “the ‘first phase’ was to raise by 1954 the most immediately needed $2.5 million portion of an $8 million long-term goal. By June 1954 barely a million dollars had been given or pledged…. Despite a one-year suspension of the Alumni Fund and an intensive peer solicitation network, only 43 percent of the alumni contributed. Fewer than a hundred graduates gave a thousand dollars or more. The campaign quietly faded away.”

Nevertheless, enough money had been raised to build a dormitory for students who chose not to join a fraternity. The John Wesley Club, known now as Malcolm X House, was given two additional wings and improved common space to host events. The construction of the John E. Andrus Center for Public Affairs, known now simply as ‘the PAC,’ soon followed thanks to the efforts of Butterfield and Trustees like George Davison, who had sought for decades to expand programs for producing “intelligent, effective leadership in public affairs.” When ground was broken for the PAC, Potts notes that Butterfield was “pleased not only by the inclinations of social science faculty members to engage ethical questions but also by their willingness to move beyond ‘over-specialization,” with Butterfield also hailing the programs to be conducted in the PAC as “one of America’s ‘most successful enterprises’ in breaking down ‘the rigidity of departmentalization.’”

Butterfield’s spirit of breaking down “the rigidity of departmentalization” lives on today through the interdisciplinary College of Letters (COL) and College of Social Studies (CSS), which, despite their modest size, boast formidable alumni networks and garner prestige as some of the most rigorous undergraduate programs in American higher education. Although several of Butterfield’s other interdisciplinary colleges ultimately failed to stand the test of time like the COL and CSS have, the College of East Asian Studies and the College of the Environment prove that Butterfield was onto something in his pedagogical philosophy. President Butterfield planted the seeds of the University, and left it to us to cultivate the garden so that it could reach the full bloom Butterfield envisioned.

This article has been corrected to reflect that the University was not called “Wesleyan College” during its early years.