c/o thedissolve.com

“The Forbidden Room” is a delirious and overflowing movie, which exists to frustrate any attempts at summation. It’s an aesthetic of too much: too much pleasure, too much narrative, too many ideas, too silly, too campy, too sublime.

But let’s pull it apart. The scholar and author Umberto Eco says in an essay about “Casablanca” that the movie runs on “the power of Narrative in its natural state, without Art intervening to discipline it.” He continues, “Two clichés make us laugh. A hundred clichés move us. For we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, and celebrating a reunion.” If “Casablanca” is a hundred clichés having a cocktail party and a chat, “The Forbidden Room” is a billion clichés having a Roman bacchanal.

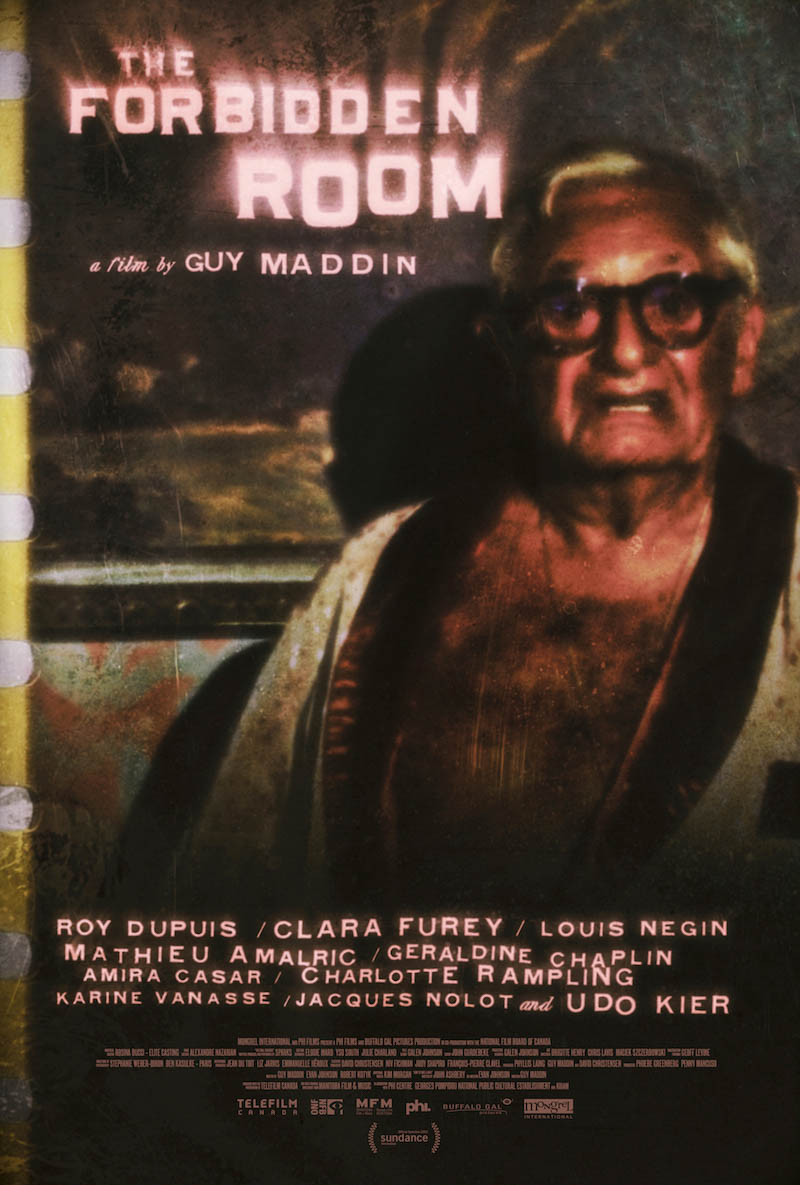

The film opens with decayed-looking, digitally treated footage of a paunchy, leering old man in a barely closed bathrobe telling us how to take a bath. The camera follows bathwater whirl-pooling down the drain, and suddenly we’re fathoms beneath the ocean, trapped in a hilariously rickety looking submarine. The crew is running out of air, but they can’t ascend to the surface because if they do, the “explosive jelly” they’re safeguarding will explode. These grizzled and hardy crew members, played by a variety of respected European art film actors, refer to themselves exclusively as “Jelly Boys.” The Jelly Boys urgently need to find the reclusive ship’s captain to inform him of the danger.

They’ve been surviving on flapjacks since, according to the film’s logic, the batter of the pancakes contains air bubbles, air bubbles the Jelly Boys need to survive. Suddenly, a lumberjack appears. Yes, you read that right: a lumberjack mysteriously appears in the submarine. He refers to himself as a saplingjack, as he is not a full-fledged lumberjack. The movie then slides into the saplingjack’s quest to rescue his ladylove, Margot, from a crew of bandits called the Red Wolves.

We subsequently enter Margot’s dream, in which she has amnesia and, finding herself in a creepy Caribbean nightclub, briefly sings about the menacing Jungle Vampire she has to avoid. Next, the billed singer, whose face has been digitally distorted and blurred out, starts singing a song called “The Final Derriere” by the glam rock band Sparks about a man who’s obsessed with derrieres and gets lobotomized in order to end his fixation.

And suddenly we’re on a volcanic island, watching a story about a “Squid Thief,” a gentleman who runs around and screams with a squid in his mouth before the mysterious woman who rescued Margot from being sacrificed to the lava-belching volcano accidentally kills him.

And so on and so on, narrative bleeding into narrative bleeding into narrative, doubling and tripling back on itself, until the movie has a nuclear meltdown, cutting from delirious climax to climax to climax, total narrative overload, until we’re watching smash cuts from kiss to kiss to kiss. This is the sort of movie that will cut from a fistfight on the wing of a plane to two men tumbling off the edge of a cliff, clutching each other and firing bedazzled pistols into each other’s faces, and next to lovers smashing zeppelins into each other.

The casting is appropriately outrageous. There’s Eurotrash art-king Udo Kier as “Count Yugh” and a murdered butler whose mustache comforts his lovely, blind wife (Maria de Medeiros, Bruce Willis’ ladylove in “Pulp Fiction”), not to mention Caroline Dhavernas of “Hannibal” as Gong, the woman who breaks all of her bones. And there’s Geraldine Chaplin, Charlie Chaplin’s daughter, who as “The Master Passion” whips the ass man from the Sparks song while wearing wraparound sunglasses and a big black hat.

The most obvious question about this movie is probably: How the hell did it get made? In many ways, it’s the superlative Guy Maddin movie. It sprung from a project he was working on in Paris called the “Séances” project, in which Maddin held a séance with actors and crew members and then, shooting over a day or so, resurrected his own version of a forgotten or lost silent film, often working from nothing more than a title or brief summary.

It was this process that snowballed into “The Forbidden Room,” with Maddin and writers Evan Johnson, George Tole, Bob Kotyk, and the poet John Ashbery all pitching in to work out the narrative’s intricate kinks. Large portions of the film were shot on live sound stages in Paris, open to public viewings. The movie pulls heavily on traditions of silent and early sound cinema, but it was shot with tiny digital cameras, initially as a project for the Internet, and the footage has been poked and prodded and composited into these fantastic, hyper-saturated images. “The Forbidden Room,” gleefully ridiculous as it is, is fiercely locked into the primal combination of image and hyperbolic emotion, which fueled cinema’s inception.

All of that being said, this is a review, and reviews are, nominally, here to tell us if a movie is good or bad, if we should watch it or shouldn’t. A certain type of thinker could easily call “The Forbidden Room” silly, overblown, too long, too indulgent. But then, what do we watch movies for? What do we want from our art and our entertainment? Art critic Dave Hickey attacks this question in a Bomb Magazine interview where he talks about hanging out in art museums as a kid. “I could walk in there every day and look at those big Bouchers, at Caravaggio, Velazquez, Fra Angelico, and they contained so much raw information that I could keep on looking, day after day….I want an image that I can keep looking at, some kind of sustained eloquence, an image that perpetually exceeds my ability to describe it.”

Do we watch for clear and rigid adherence to structure, or for well-crafted dialogue, or for well-drawn characters with “realistic” psychologies? Or, as Hickey suggests, do we simply want to be entertained?

“The Forbidden Room” is outrageously, powerfully entertaining. Its constantly shifting images and compounding narratives exceed our ability to describe it with words, and yet it engages us on a visceral, fundamentally pleasurable level. If the movie doesn’t at least pique your interest, I don’t know what cinema has to offer you.