Exposing the ardor of investigative journalism, “Spotlight” offers a thorough critique of the Catholic Church.

“Spotlight” is not only the best movie about journalism in recent memory, it is arguably the best movie of the year. Although still in limited release, “Spotlight” has captivated critics since its release in select cities over a month ago and continues to build steam in a time when movies have been losing millions of dollars upon release. Currently a favorite for Best Picture at the upcoming Academy Awards, the best quality of “Spotlight” is its captivating performances that somehow create tension in a story that most audience members already know the ending to.

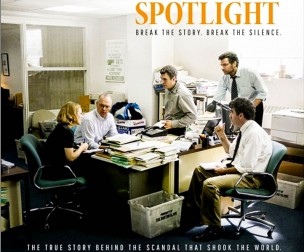

Mainly focusing on the Boston Globe’s exposing of the Catholic Church for covering up rampant sexual abuse against children by its priests in the early 2000s, “Spotlight” paints a more complicated picture of the Catholic Church than one would think. Led by Mark Ruffalo, Michael Keaton, and Rachel McAdams, who play investigative journalists on the Globe’s Spotlight Investigative Team, “Spotlight” begins at a vulnerable time for the Boston Globe. With the arrival of new Editor-in-Chief Martin Baron, played in full monotone and gravitas by Liev Schreiber, the Globe and its unique Spotlight team face the same cuts that Baron put in place during his time at The Miami Harold.

Worried that Spotlight’s hard hitting investigative work will fall by the wayside in a new era of journalism, Spotlight’s editor, Walter ‘Robby’ Robinson, played by Michael Keaton, agrees to take on a story about Catholic priests molesting children that Baron believes could have legs, but hardly anybody else does. One of the toughest aspects of pursuing and subsequently publishing this story in Boston is that over 60 percent of the Globe’s readers at the time were Catholic, as were most of the reporters covering the child molestation in the Catholic Church for the Globe and Spotlight. The embodiment of the criticism and skepticism that came with the Globe’s pursuit of the story is Editor Ben Bradlee Jr., played with much needed humor from John Slattery. Slattery played Roger Sterling on “Mad Men,” created by Matthew Weiner ’87. Bradlee is skeptical that the story goes beyond a “handful of bad apples,” which becomes a broader signifier of those who deny the epidemic of sexual abuse in the church as the film progresses. Nevertheless, the movie pursues the story and eventually begins to discover the Catholic Church’s coded language for child molesters.

A difficult feat for any film, “Spotlight” makes painstaking research come off the screen as vivid and tense storytelling by deploying an array of techniques that show how a team of reporters navigate through the bureaucracy of court documents and church directories. “Spotlight” makes research and reporting seem compelling by revealing the stories of the people reading the documents, not just the documents themselves. Furthermore, the people, whose traumatic stories live on through those documents, are depicted in moving interviews that are hard to watch without thinking of the horror that marked these children’s first sexual experience. One of the most compelling and underrated performances in “Spotlight” is by Michael Cyril Crieghton, who plays a victim of sexual abuse named Joe Crowley. In his devoted emotional portrayal of a sexual assault survivor, Creighton is able to put the audience in the shoes of a child whose entire adult life has been scarred by the predatory acts of a priest. Adding extra weight to one of the film’s key motifs, Creighton delivers one of the film’s most powerful lines when he talks about how he, “couldn’t say no to God,” when a priest sexually abused him.

Of all of the Spotlight reporters, Mark Ruffalo’s character gives the best portrayal of a tireless and intense reporter. Constantly sprinting between the Globe’s office, Boston Courthouses, and his run-down apartment where he rarely sleeps, Ruffalo’s Mike Rezendes shows the audience just what it takes to be a poorly paid reporter doing incredible amounts of work that seemingly lead to no payoff. Rezendes’ intensity comes through most vividly when he goes on a tirade against his editor, Robby Robinson, for perpetually delaying the story until the Globe has all of the facts. Evidence is incredibly hard to find given the Catholic Church’s influence in Boston, but it is critical in order to reveal the systematic cover up of sexual abuse by the archdiocese rather than a mere “handful of bad apples.” In his tirade, Ruffalo embodies the frustration of every reporter who has wanted his or her work to mean something and result in real change. The editor argues that until the story is published, all of the twelve-hour-plus days and endless trips to Boston Courthouses will mean nothing for the lives of the victims, but neither will the story itself until all of the facts are present.

Even if “Spotlight” doesn’t win Best Picture, it will still go down as one of the best movies about journalism ever, or at least what journalism should be. Everyone, regardless of their experience in journalism, has a bit of Mark Ruffalo’s character inside of themselves. There is a desire for truth and meaningful progress that “Spotlight” evokes in its viewers that will hopefully lead to more meaningful reporting in an era of page views, GIFs, and shares. To watch “Spotlight” is to yearn for the truth, even if you already know what it is.

Comments are closed