“Experimenter” sheds new light on Stanley Milgram's infamous experiments.

You walk into an experiment you signed up for, which was advertised as a study of how people learn. After picking out of a hat, you are assigned the role of “teacher,” and the man next to you “student,” which means that you’ll be “teaching” him word pairs and giving him brief electric shocks of increasing intensity as a punishment when he answers your questions wrong. You receive a brief shock yourself to get a taste of what you’re inflicting on the other man—it’s not pleasant, sure, but it doesn’t seem life-threatening or dangerous.

You walk into an experiment you signed up for, which was advertised as a study of how people learn. After picking out of a hat, you are assigned the role of “teacher,” and the man next to you “student,” which means that you’ll be “teaching” him word pairs and giving him brief electric shocks of increasing intensity as a punishment when he answers your questions wrong. You receive a brief shock yourself to get a taste of what you’re inflicting on the other man—it’s not pleasant, sure, but it doesn’t seem life-threatening or dangerous.

At the beginning, the man seems to have learned the word pairs well enough. But soon, he starts getting answers wrong, and you’re forced to give increasingly intense shocks—the highest is 450 volts—as the “learner” starts to protest and cry out, eventually begging to be released from his chair. The experimenter, however, insists that you continue the experiment and assures you that while the shocks may be painful, they are not dangerous.

This is an experiment not about learning but about obedience, carried about by Stanley Milgram in the 1960s at Yale, where he tested 40 participants and found an overall rate of 65 percent compliance with the experimenter. This means that 65 percent of participants believed they were giving 450-volt shocks to a participant that had, after begging to be released, eventually fallen silent and stopped responding to questions about the word pairs. (The “learner” was actually a confederate who was not receiving shocks and playing a tape recording of the protests). Milgram did the experiment with the Holocaust in mind, curious how such a massive population could carry out violence on such a large scale.

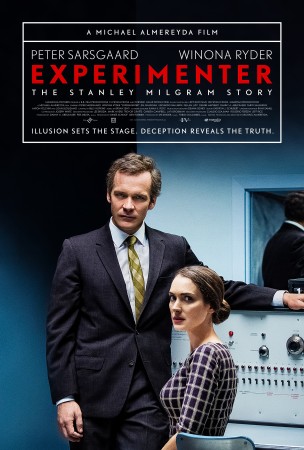

As a psychology student, I’ve been over this experiment a thousand times—heard it narrated by three different professors, seen it explored in a film Milgram made of the experiment, wrote it on flash cards, and answered multiple choice questions on it. But never have I seen the experiment as a vehicle by which to depict the life and career of Stanley Milgram himself, a man with a personal career and family who was deeply affected by these experiments. “Experimenter: The Stanley Milgram Story” did just this. Screened in Shanklin by the University’s Psychology Department on Wednesday, the film has what you might call an all-star cast: Peter Sarsgaard stars as a quietly rebellious and consistently mournful Milgram, and Winona Ryder plays his wife. Jim Gaffigan plays the actor appearing to be shocked by participants, and a cameo by Taryn Manning of “Orange is the New Black” as a participant in the experiment is thrown in. It’s written, directed, and produced by Michael Almereyda, who imbues the film with a bizarrely gloomy but somewhat playful quality.

“Experimenter” is narrated by Milgram, partially via his own voice and partially when his character turns towards the camera before, after, or in the middle of scenes, and, “House of Cards”-style, makes a commentary on the current scenario. His voiceover narrations focus more on the general scheme of his life, and he dictates events in a timeline-esque style: “Sasha goes back to school,” “I get a job at Harvard,” and the like. His narration transcends the limits of the scene itself, as if he’s a ghost reliving these moments of his life, moving in and out of them and picking out the important parts, discarding the ones that are less significant. In one scene toward the end, he walks into the hospital with his wife, and his voice dictates, “This was the year I died.”

However, major events aren’t always announced—while we do watch Milgram ask his future wife to move in, a scene sandwiched jarringly between cuts of the experiment itself, we only hear about “a wife he has to get home to,” or watch the pair walk into a building toting a baby, without any previous mention of marriage or children. The scenes are sometimes completely and deliberately false-looking—one, where he visits his mentor and former boss Solomon Asch, is enacted against what look like flat pictures of what the backgrounds would be. The portrayal seems completely constructed by Milgram himself, giving us only the parts he remembers and feels were important.

Throughout almost the entire film, scenes are washed with drab gray light, emphasizing Milgram’s pessimistic tone as well as the somewhat disturbing discoveries he makes, which seem to shock and depress even him. His other experiments, which are less well-known but equally fascinating and monumental, do not all focus on obedience—in one, called the Small World Project, he discovers that the average person has 5.5 degrees of separation between some billion other people in the United States. But the initial experiment seems to throw a shadow over all his subsequent work, constantly coming back to haunt him, whether through criticisms of the experiment’s ethics that threaten to ruin his career or a friend at a dinner party requesting that he carry them out in countries beyond the United States.

The film’s version of Milgram exudes a sort of “tortured artist” quality—but instead of an artist, he’s a tortured social psychologist. His work touches every part of his life: During the party at which he meets his wife and tells her about his career, it becomes clear that he’s analyzing the dynamics of the party itself. But instead of seeing the positive implications of his work, such as the possibilities it opens up for the prevention of violence carried out on a massive scale, he seems more haunted by it, both in the way it exposes the ease with which you can convince humans to carry out violence, and in the way it sticks with him throughout his entire career. At one point, he announces to his students that Kennedy has been shot, and one of them suggests that he’s probably carrying out an experiment on them. When he turns on the radio to prove it, they suspect it’s a false radio feed he recorded for the so-called experiment.

The sun seems to begin rising, though, at the end of the film. While people on a street look up towards the sky (one of Milgram’s experiments was to plant people looking up at the sky, which results in those surrounding to look up as well), Milgram’s voice narrates with a verbal shrug, “You could say we’re puppets”—a notion that much of his work seems to suggest. However, he points out that he believes we’re puppets with perception—that sometimes we can see the strings, and that this promises the possibility of liberation from the bleak results of his experiment. His gloom is countered by cautious hope, echoing the sentiment that knowledge truly is power. Milgram left behind an imperative to anyone who learns of his work: to find those strings and to break them, hopefully preventing some of the violence that haunts human history.