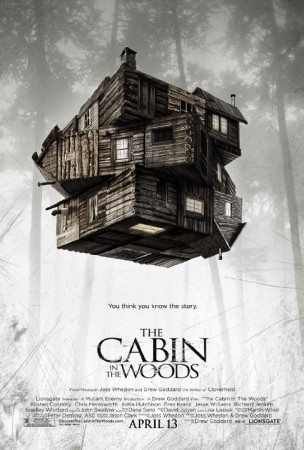

As part of their 2015 Halloween Horrors Week, the culture site The AV Club released a list of “The 25 Best Horror Movies Since 2000.” As a primer for those unfamiliar with the genre, the list was a strong showing, including recent critical darlings like “It Follows” and “The Babadook” alongside darker pulpier fare like 2005’s gruesome outback slasher “Wolf Creek,” and 2006’s Korean monster-piece “The Host.” Still, one entry proved disappointing: Drew Goddard’s 2012 meta-horror “Cabin in the Woods,” which the site chose to insert at the number fourteen slot. True, it’s only been three years since the film’s theatrical release. Regardless, it’s probably time we acknowledge that “Cabin in the Woods” is a bad movie.

Written by Goddard and Joss Whedon, “Cabin” presents itself as something of horror satire in line with Wes Craven’s “Scream,” which deconstructed the slasher genre nearly twenty years ago. Goddard’s film plops a collective of standard horror stereotypes—the jock, the stoner, the nerd, etc.—in the titular cabin and forces them to contend with a violent family of zombie cannibal rednecks, who attempt to pick off the protagonists one by one. From the beginning, however, it’s clear that things are not as they seem. Each character defies their appointed role, and proves wise to the standard mistakes of the genre’s normal cannon fodder. Furthermore, it seems that the whole scenario is being manipulated by a shadowy organization who appear strangely invested in the demise of these college students.

It’s not an unpromising setup. Unfortunately, the execution is severely lacking. In stark contrast to Craven’s “Scream” and other deconstructions such as the fantastic 2006 “Behind the Mask: the Rise of Leslie Vernon,” which turns the standard un-killable slasher into a tradition-conscious rookie, “Cabin in the Woods” is consistently smug and self-satisfied. Its means of subversion prove increasingly bulky and uninteresting, and rarely is the film ever close to frightening. Rather, the final product reads less like a love letter or a satire and more like a poorly edited Wikipedia page.

Perhaps this sounds a bit like defensiveness. Perhaps it is. But the horror genre has been ripe for subversion and unpacking since even before the days of “Scream,” when Wes Craven explored the idea of Freddy Krueger as a modern-day fairytale villain who has an impact well beyond celluloid in the daring if uneven “New Nightmare.” For, as much as horror is mired in cliche, it’s also a genre that has readily opened itself up to self-examination. Even the lackluster slasher revival that followed “Scream” often concerned itself with the strictures of storytelling and trope.

As opposed to “Cabin in the Woods,” however, these films always managed to understand the visceral mechanics of the genre in addition to the structural ones. At its best, when it relocates to the underground bunker of the manipulative institution behind the mayhem, “Cabin in the Woods” plays like nothing more proficient than a clipshow of better movies via a series of generic brand knockoff archetypes run amok. Still, even with a subterranean labyrinth overrun by homicidal clowns and “Chopping Mall”-style Kill Bots, the film never manages to illicit anything close to a scare. Strangely, for a film that so often seems to look down on the horror genre’s love of bloodletting (after all the central metaphor posits horror audiences as demanding some manner of yearly blood sacrifice), the climactic massacre feels frustratingly weightless. You’re more likely to feel the heft in “Friday the 13th Part VII’s” sleeping bag kill than in any of the blasé CGI slaughter of those last twenty minutes.

The degree to which the film relentlessly toots its own horn does little to help. Say what you will about the commentary that “Cabin” is making, but it’s certainly not new. But, what the film lacks in innovation it makes up for in ego. Not only does the film sport an ending that reads as a self-important diagnosis of the state of horror, but it rarely levels a single unique accusation. It has very little to say about the genre’s troubling tendency for misogyny or xenophobia, and a whole lot to say about how dumb it is that characters so often tend to split up. That the slasher genre in particular often resembles more of a production line for blood-drenched money shots than a cohesive narrative is something to which most writers and directors working within it would readily admit. That “Cabin in the Woods” has little to offer by way of meaningful alternative is something the film seems desperate to cloak with the increasingly baroque machinations that make up its central plot device.

This is all the more frustrating when one takes into account how poorly the film handles its own horror elements in the first half. In what appears to be a send-up of “The Evil Dead” crossed with “The Hills Have Eyes,” the film confronts its characters with a set of generic monsters that do little to prove the picture understands what made those films actually work. It’s a well known fact of writing that your character being bored is not an excuse for a boring story. Still, “Cabin” seems to think the best way to prove that reused horror elements need to be forgotten is by making them far more groan-inducing and toothless than they were to begin with.

Perhaps most troubling, however, is that the film’s cries of recycling make “Cabin” seem completely ignorant of the history and the makeup of the genre it lampoons. Horror has always been a genre where deviation percolates at the outskirts while the majority attempts to capitalize on the dying breaths of the previous trend. Furthermore, if “Cabin in the Woods” is meant to appeal to those buffs of the genre who will most recognize its limp citations of scarier films, it fails to realize that these are the people who are taking the time to explore the regions where newness is beginning to bud. If Goddard and Whedon really wanted the genre to evolve and transform, they should have released a flyer urging viewers to see a Ti West or Adam Wingard film, rather than complaining about the tropes that “Scream” had long put in their place. While filmmakers like West and Wingard and overlooked anthology pieces like “V/H/S” were languishing in obscurity, “Cabin” took up space without even tearing down the honchos of the genre that were then relevant. One might argue that “Cabin” was a reaction to some of the recent horror remakes with which studios like Platinum Dunes were flooding the market, but it failed to skewer the combination of mean-spirited escalation and inability to understand the core of the concepts that made those films feel lifeless. Instead, “Cabin” itself proved that it couldn’t see what made the core archetypes at the foundation of the genre feel vital to begin with, and stretched its misunderstanding to over 90 minutes and 30 million dollars.

An effective send-up of a genre needs a lot more to say than “genres often follow a certain set of rules,” a point which “Cabin” only seems to reach beyond in those last five minutes. When “Scream” premiered it spoke both to the rote violence of the slasher, but also to the escalating paranoia about violence in popular film that reached a fever pitch three years later in the wake of the Columbine Massacre. “Don’t you blame the movies, Sid!” serial killer Billy Loomis bellows at his disgusted girlfriend in the film’s finale; “Movies don’t create psychos. Movies make psychos more creative!” With that, Craven ensured that his picture would not simply be a diagnosis of its contemporaries and forebearers, but an attempt to restructure what came next. Frustratingly—especially for a writer as seemingly attuned to the cultural pulse as Whedon—“Cabin” has nowhere near those aspirations. It feels consistently limp and blinkered: too reliant on references to function on its own merits and yet still too blind to the actual makeup of the genre it’s interacting with. Three years earlier, “House of the Devil” approached the legacy of the possession film and revitalized it. Four years earlier, “The Strangers” (one of many pictures “Cabin” impotently cites) recharged the home invasion subgenre with quiet malice. How can Goddard and Whedon’s film be classified as a love letter when it can barely name the qualities or account for the goings-on of its sweetheart?

Ultimately, what’s most ironic is that “Cabin in the Woods” seemed wholly unaware that it was itself a recycling, an overdone restatement of films like “Scream,” “New Nightmare,” “Behind the Mask,” and even “Tucker and Dale vs. Evil.” Just like all the remakes with which it seemed so incensed, “Cabin” threw new money at old ideas, and confused winking with subversion and reinvention. In many ways, the core conceit of the film was right: mainstream horror does deserve better. If Goddard and Whedon truly believed that, however, they would have dumped their script in the shredder, and endorsed the auteurs who were already making better things happen. There’s very little that’s frightening about self-satisfaction.

Leave a Reply