A few scenes into “Crimson Peak,” Edith Cushing (Mia Wasikowska) defends her manuscript to a publisher by claiming that it is not a ghost story. Rather it merely contains ghosts, which are metaphoric windows to the past. This not so subtly prepares the viewer for what the next two hours contain: a gothic melodrama that just happens to occasionally contain ghosts. This melding of genres is a challenge even for the mind of Director Guillermo Del Toro, and while “Crimson Peak” may be one of his more inventive works, it is also one of his weakest.

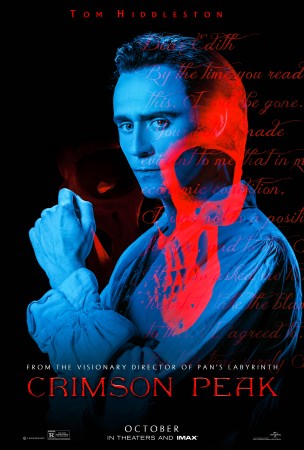

The film’s plot is essentially divided into halves. Edith, a resident of late 19th century Buffalo, falls in love with Sir Thomas Sharpe (Tom Hiddleston), the seemingly quintessential Victorian love interest. After her father dies under suspicious circumstances, Edith chooses to marry Thomas and join him and his sister (Jessica Chastain) in their dilapidated ancestral home of Crimson Peak in England. Once there, a devious plot is revealed as the Sharpes’ behavior becomes increasingly malevolent. Sometimes spooky ghosts appear.

Aesthetically, the film is breathtaking. Del Toro turns the Sharpe abode into the visual playground he’s always wanted. Moths, snow, and pervasive crimson muck make every frame worthwhile. Flowing costumes bring vibrant colors into the fray, and the ghosts themselves are fascinating to witness in their elegant spasms.

Even more impressive are the performances. Wasikowska is one of the few participants in the film who is able to fully balance the tones “Crimson Peak” is going for, and she does so with captivating humanity. Hiddleston, and Chastain are deeply enjoyable to watch as well. Hiddleston is able to provide a complex warmth to his relationship with Wasikowska, making their chemistry both believable, and disquieting. Chastain fully inhabits the melodramatic world, and takes on an aura of sinister brooding that would make a Disney villain blush. “That’s exactly what our mother told us in her last moment,” she whispers upon being called a monster, barely containing her icy glee as she stabs her next victim. In each shot she is fully entertaining, but is also fully in control of her unusually overblown performance. Less impressive is Charlie Hunnam, who still manages to give less of a stone-faced performance than usual.

But underneath the surface, there is a lack of substance to the electrifying style. The first half of the film (which takes place in Buffalo) drags before the film can fully hit its stride, or even a consistent pace. The true tragedy of “Crimson Peak” is that it can never find its balance of tone, or genre. Del Toro, who reached such precision in the synthesis of childhood fantasy, and horror in “Pan’s Labyrinth,” fails to reproduce a similar effect here. While at times the tension, and melodrama work in concert to create a captivating atmosphere, they are more often at odds with each other. The cast can only do so much with some truly terrible lines. The ghosts are inherently fantastical, but there is something more real to their horror, and suffering than the ridiculous heights the melodrama reaches. At one point, Chastain comments on the inevitable mortality of butterflies as we are given a microscopic view of ants eating their eyes. While the moment was, to some extent, unsettling as intended, the theater laughed more than it squirmed. In “Crimson Peak,” Del Toro’s two great narrative passions, horror, and character drama, detract from each other in a way they have not before. A climactic moment in which Chastain pushes Wasikowska off a ledge feels more like a punchline than a dramatic twist.

The rare moments in which fear is not overpowered by ridiculousness are when the ghosts are involved. On screen or off, they add a strong dose of horror, and anxiety to the narrative. The film’s climax also manages to use the amplified drama to its advantage, finally providing the heightened tension Del Toro is a master at creating.

For the music, Del Toro turns away from the bombastic sounds of Ramin Djwadi’s “Pacific Rim” score, and instead opts for the quieter intensity of composer Fernando Velázquez. It pays off. Velázquez shows impressive versatility, and restraint, offering sinister strings or a piano when needed, and at other times utilizing the full orchestra to increase tension. He’s able to smooth over the film’s tonal inconsistencies to some extent, but music can only do so much.

“Crimson Peak” may fail at its fundamental goals, but it remains a beautiful, and highly enjoyable film on the surface level. It also serves as a fascinating case study of a director firing on all cylinders, and yet still failing to execute the emotional experience they wish to provide. Last week Del Toro tweeted, “When 1 movie gets made, 3 get released: The one the audience wants. The one the studio sells. The one that was made. Sometimes they coincide.”

Sometimes they don’t.

Leave a Reply