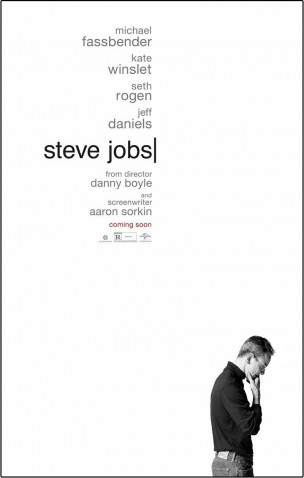

“Steve Jobs,” written by Aaron Sorkin and directed by Danny Boyle, is a bit of a mess. Part of this comes from the film’s ambition, which strives to condense the essence of its subject and Apple visionary into little more than three self-contained vignettes detailing the launch of the Macintosh computer in 1984, the NeXT educational computer in 1988, and the iMac a decade later. These sections are interspersed with a series of flashbacks detailing Jobs’ relationship with Apple’s ex-CEO John Scully (Jeff Daniels) and his ousting from the company after the failure of the original Macintosh. But, for the most part, Boyle and Sorkin keep the audience contained in time and space, weaving backstage in extended shots that call to mind “Birdman” melded with the writer’s own classic walk-and-talks.

Boyle, a distinctly kinetic filmmaker, proves relatively reserved here. “127 Hours” also found its protagonist restricted to a single setting, but there Boyle found ways to leap beyond the crevice in which James Franco’s Aron Ralston was trapped. In “Jobs,” he allows himself to remain pinned within the four walls of auditoriums and boardrooms. Beyond a few dazzling introductory montages that detail the year in which each scene takes place (and a wonderfully staged digression into the history of a failed Russian satellite), “Jobs” is a stationary film. Certainly, it thrashes against its constraints, but it also never feels the need to break too severely from its central gimmick. It’s tightly woven, singularly dedicated, and claustrophobic. The result is a sort of woozy chaos that, intentionally or not, seems to imitate just what it might be like to be inside its subject’s skull.

“Steve Jobs” primarily roots itself in Sorkin’s script and Michael Fassbender’s portrayal of the titular genius, whose malice, ego, and perfectionism are on full display in nearly every line of dialogue. While Sorkin never seems interested in going too far beyond the concept of Jobs as an asshole visionary, Fassbender manages to enliven that caricature in nearly every scene. He’s icy and magnetic, completely aware of how cruel he is in stark contrast to Sorkin’s imagining of the aloofness of Mark Zuckerberg in “The Social Network.” Though it is exceedingly easy to compare that film with “Jobs” (especially since David Fincher was originally slated to direct in Boyle’s place), the link ultimately proves somewhat superficial. Whereas “The Social Network” was mournful and paranoid, “Jobs” is exceedingly triumphant, if not always in tone then in the sort of grand gestures that defined the Apple brand under Jobs’ tenure. Even the failure of the Macintosh is painted in grandiose colors, a sort of Greek tragedy that pits Jobs’ impractical vision against the pragmatism of his mentor and the Apple board. Rather than leaning into his normal urge to deify men such as Jobs, however, Sorkin allows these scenes to bask in the petulance of the film’s central figure. When confronting Scully in a last minute board meeting, Fassbender’s Jobs rants with the wild impropriety of a vindictive child. As rain streaks the room’s large windows, Boyle’s camera tracks between a gesticulating Fassbender and a staid Daniels, who sits partly shrouded in darkness. While on a visual level the scene might seem designed to support Jobs’ vision in the face of unimaginative management, the rhythms of the performances tell a completely different story. Throughout the film, no more so than in this scene, “Jobs” shows how its subject’s megalomania backs him and those who care about him into unsavory corners, how he forces those very situations that destroy his relationships, often for no other reason than to make a point.

While the film is ultimately Fassbender’s rodeo, the supporting members of the cast do a fantastic job serving as a kind of Greek chorus to the Apple founder. Kate Winslet turns in a beautifully subtle performance as Joanna Hoffman, the brain behind much of Apple and NeXT’s marketing. Though viewers are initially tempted to focus solely on Winslet’s affected Polish accent, the work she does beneath it is mesmerizing. By turns shocked and bemused by her boss’s arrogance, she reminds him that she’s the only person able and willing to stand up to his vision and demand that he attend to his failures, most notably as a parent.

In addition to his professional history, the film explores his refusal to father his daughter Lisa, even as her mother is forced to go on welfare. If this is the thread that most often devolves into cliche, it is buoyed by Sorkin’s refusal to excuse Jobs’ absence. Still, the writer does a less impressive job humanizing Lisa’s mother Chrisann Brennan (Katherine Waterston), whose insistence that Jobs pay attention to their child is written in such broad strokes as to highlight her eccentricity over her remarkable endurance. Waterston does her best to add dimension to the character, but Sorkin’s script seems determined to reduce her to an unstable, if mistreated, hinderance to Jobs’ vision and his relationship with his daughter. When the picture does circle back to that relationship in its final scene, it is mired in a sentimentality that it had largely been able to avoid. That this is immediately followed by the only sequence in which the film could ever be deemed worshipful of its subject only adds to the weakness of that final interaction, iPod joke and all.

Much like in “The Social Network,” Sorkin does blessedly little to explain his subject’s flaws. Though the script does indulge the idea that the crude circumstances of Jobs’ adoption were partially responsible for his need for control, Fassbender plays the reveal almost as a joke, a dodge. When he and Daniels’ Scully debate his culpability in his first adoptive mother’s decision to return him to his birth parents after a month, Fassbender manipulates the information as though he sees it less as the root of his dysfunction, but rather a way to name that dysfunction. It’s a powerful character moment not simply because the anecdote is itself powerful and jarring. Rather, it succeeds because Fassbender turns what could have been an external explanation for a deeply entrenched set of behaviors into an internal function of those very behaviors. A lesser actor might have allowed the beat to read as awkwardly as it does on the page—a sort of editorial deus ex machina sent down from the spottily researched heavens to transfigure a visionary bastard into a merely troubled great man—but Fassbender works to complicate it in ways that avoid obviousness.

It’s moments such as these that make “Steve Jobs” worth seeing, small manipulations of iconography and tone that work against the current of the traditional biopic, and plainly reveal the seams of the work being done on screen. It’s rare to see a film that seems content to bloat and sag and run off the tracks in pursuit of such a codified Hollywood ideal—the scripting and reportage of an Important Life—much less one that is able to do so gracefully. On the surface, “Jobs” can feel like one of the products produced by its titular character: sleek, crisp, functional. Beneath that, however, is something far knottier, a film whose circuitry can reveal itself to be deliriously tangled and unstable when called upon. As a factual document, “Steve Jobs” has already come under heavy fire. Still, as a piece of filmmaking, it is perhaps the most fitting portrayal of the man that will be made: a work of cinema that simultaneously wants to live inside the strictures of a model well-understood, while recklessly dismantling it with gleeful abandon. Though it may not always “think different” as well as it assumes, “Steve Jobs,” somehow both wild and contained, never stops thinking.

Leave a Reply