It seems as though once a month, the Lifetime channel releases a new film about cyberbullying, each subsequent entry into the canon just a little more extreme than the last. Most follow a somewhat linear path: a teenager is made fun of online or via text, then either commits suicide or learns not to listen to the cruel digital jabs wafting in from his or her peer group. Still, despite the channel’s seeming obsession with bringing wider attention to the very real issue of online harassment, not one of these movies really seems to accomplish anything. At the end of the day, they all read like urban legends, certain as they are that technology is not just a vehicle for sadism but a sadistic force in and of itself. Over the years, these films have ranged from dramas to PSAs to horror movies. So Lifetime executives must be kicking themselves now that an actual horror movie has dealt with cyberbullying much better than any of their made-for-television cautionary schlock ever has.

This is not to say that “Unfriended,” directed by Levan Gabriadze and written by Nelson Greaves, is a fantastic or nuanced look at an insidious social issue. But, in contrast to those Lifetime PSAs that seem geared primarily toward parents still incredulous over sexting, “Unfriended” does manage to capture the bizarre claustrophobic terror of being trapped online with a seemingly endless cohort of abusers. It’s a picture that, despite succumbing to some intermittent silliness and underwriting, manages to be jarring in ways that it really should not be. It’s maybe the definition of a film that is better than it has any right to be. It plows forward without pretentions or the desire to really say much at all, but in the process stumbles upon a discomforting approximation of what it feels like to be hunted and toyed with while alone with your computer.

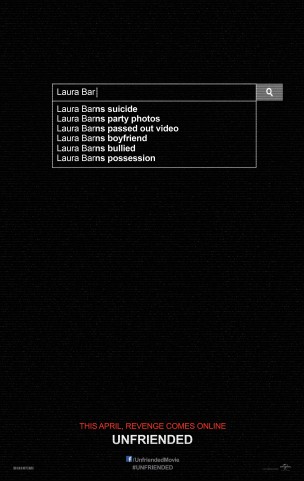

The premise of the film is relatively simple, drawing on the basic trappings of ghost stories and teen horror movies. Blaire (Shelley Hennig) is on her computer on the one-year anniversary of her friend Laura’s suicide. Following the distribution of a mortifying YouTube video, Laura was dogged by endless harassment. She eventually shot herself while another individual taped from a distance. This too was posted online.

After rewatching the video of her friend’s death, Blaire begins a video call with her boyfriend Mitch (Moses Jacob Storm) and three other friends. Their call, however, is soon interrupted by an anonymous individual who none of them are able to block. The new caller claims to be Laura and demands to know which of her friends was responsible for posting the original video of her online. If whoever it is refuses to turn themselves over, everyone dies.

Though the plot sounds like the pilot of “Pretty Little Liars” or the dreadful horror remake “Sorority Row,” “Unfriended” differentiates itself via one gimmick: the entire film is an unmoving shot of a computer screen, the story told through video and chat windows, online clips, and other social media. Though the idea seems destined to become tiresome quite quickly, Gabriadze somehow manages to keep it fresh throughout the entire film, moving windows around to create an unnerving digital collage of the familiar and welcoming made grotesque.

This is undoubtedly the film’s greatest strength and what allows it to escape the pitfalls of its generic story. “Unfriended” is uncannily in touch with not just the basic lingo and brands of the online world it wants to engage with but also with the small sensory details and textures that go along with those experiences. Though the picture does present the audience with a fair share of jump scares and a few scenes of disturbing violence, it’s at its most frightening when it simply relies on the familiar iconography of social media, curdling and perverting sounds and visuals to establish growing unease. Rather than presenting the audience with a visualization of Laura’s ghost, “Unfriended” simply offers the audience the blank profile template from Skype: that flat, white, sexless bust of a person. What was no doubt designed as a way to symbolize the familiar and the human is then turned into something spectral and sinister. Perhaps to a user setting up a profile on a site, that photo-stand-in encourages the adding of personal images or details. In the film, though, it offers the reverse: an individual once personal reduced to a vaguely human void.

“Unfriended” uses sound to brilliant effect, toying with the chimes from chat logs and inboxes to shatter silence or overwhelm the audience with the sudden cacophony of overlapping pings and screeches. It’s a fantastic simulation of what it feels like to dread being contacted-— a sound designed to say, “someone wants to talk to you,” remade into the promise of pain or wickedness. Anyone who has found themselves feeling trapped in the path of digital abuse can understand that terror: the promise that once you open that window there is so much more to come. In the same way that a film like “Jaws” might announce the approach of its titular character through the deepening and quickening horns of John Williams’ score, “Unfriended” anticipates each escalating bit of cruelty with that cheerful corporate pulse: like a doorbell that somehow implies exactly what’s waiting across the threshold. Before seeing the film, it seems absurd that one might think, “don’t open your chat log,” with the same fervency as, “don’t go into the water,” or, “don’t check out that noise in the attic.” The minor brilliance of “Unfriended,” though, is how well it manages to transpose the best rhythms and tropes of its genre onto the online canvas.

For years, horror films have had an unfortunate obsession with the Internet. Failures such as “Feardotcom” (2002) and “Smiley” (2012) have more than proven this. However, where past entries have treated the online sphere with strange awestruck confusion or Luddite-ish distrust, “Unfriended” engages with the space as a film might any other landscape. Gabriadze is not so much interested in uncovering the fundamental evil of social media as he is in twisting the familiarity of those interfaces and applications to recreate the sense of the comfortable turning vicious. More so than many other pictures attempting to say something about what it means to be online, “Unfriended” is fascinated by the minutiae, and how ultimately definitive of the experience those small sensory details can be. Like any good horror film, “Unfriended” recognizes that all it takes to create fear is to infect one small cell of a warm familiar world and watch the gleeful sickness spread.

Leave a Reply