Over the past few weeks, The Argus spoke to leaders and members of four activist groups that confront the Israel-Palestine conflict: Wesleyan United with Israel, J Street U, Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), and Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP). In doing so, we sought to understand the state of Israel-Palestine activism on campus, the tension that has surfaced in its past, the issues with which it deals in the present, and the conversations it hopes to continue in the future. Meet the key players here.

The Shifting Landscape

Last year, when Rebecca Sussman ’18 visited campus during WesFest, she struck up a conversation with a student about the conflict in the Middle East. When Sussman used the word “Zionist,” the atmosphere became tense.

“You can’t say that here,” Sussman remembers the student telling her. “It’s a dirty word.”

Sussman hopes that this will soon no longer be the case. This fall, she, along with first-year students Rachel Alpert, Elisa Greenberg, and Matthew Renetzky, reinstated Wesleyan United with Israel, a pro-Israel group that supports a two-state solution and opposes the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement. Tasked with building a new membership, they remain frustrated by perceptions about what it means to support Israel.

Renetzky emphasized that Wesleyan United with Israel is more complicated than right-wing stereotypes often suggest.

“I’m going to borrow a metaphor from Alan Elsner,” Renetzky said. “There’s a difference between being a fan and a cheerleader. As a cheerleader…you can be losing 50-3, and you’re still cheering the team on…. Or you can be a fan, who feels passionately about the team but who is still willing to criticize [them] and see them for what they are. We’re almost hyper-realistic. We’re acutely aware of every problematic thing, but that doesn’t mean we still can’t support this country.”

Maya Berkman ’16, a current leader of J Street U at Wesleyan and northeast regional co-chair for J Street U, pointed out that the differences among the four groups on campus concerned with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are not always as great as they seem.

“I think there’s a lot of overlap,” Berkman said. “The students who are engaged with this issue, or at least seriously engaged with this issue, [compose] a pretty small group of people, and you start to recognize the same faces at various events…. I think on such a small campus it’s problematic when we try to divide ourselves so definitely between the different groups.”

According to Berkman, J Street U is relatively centrist, a position that appeals to her because of its capacity for nuance. J Street, the parent organization of the college chapters, is a pro-Israel group that supports a two-state solution.

“I think having our political focus being the establishment of a two-state solution does put us kind of in the center in a way that’s unique, because we encompass students who fall to our right and our left,” she said.

To J Street U’s left stands the newly established campus chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), which, among other things, calls for an end to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem. Yael Horowitz ’17, a founding member, noted that although JVP has a strong relationship with Studens for Justice in Palestine (SJP) and a neutral one with J Street U, tension exists between JVP and Wesleyan United with Israel.

“That stems from deep ideological differences,” she said. “I think [Wesleyan United with Israel] also [has] problems with the way we operate. Making Jewish spaces political is a problem [for them], and I think us not turning away from politics and from the issue is the opposite of what they do in a lot of ways, because they’re trying to celebrate culture without turning towards politics. That’s an obvious point of tension.”

Moreover, Horowitz added that although the conflict in the Middle East is far removed geographically, it is closer than many people would like to believe.

“The occupation of Palestine is not happening at Wesleyan, but Wesleyan students are complicit in it, and are always in a lot of ways unaware of it,” she said.

Many choose ignorance in pursuit of comfort, said Horowitz, but JVP aims to be a source of education and discomfort, especially within Jewish spaces.

“I think success has to be measured in the amount of people that you reach and the amount of people who start actually thinking critically about it,” she said.

Still to the left of JVP is SJP, whose members declined to be interviewed for this article.

“We’ve decided we’re not going to do any direct interviews because our group has a lot of diverse opinions and we can’t reduce ourselves to one voice (even if that voice isn’t officially a spokesperson),” wrote SJP member Alice Markham-Cantor ’18 in an email to The Argus.

According to the national SJP website, the organization supports the BDS movement and denounces the Israeli occupation.

Boycotts, Protests, Vandalism

Last spring, the Wesleyan Student Assembly (WSA) passed a resolution in favor of joining the BDS movement, which, according to its website, campaigns globally to withhold support from Israel until it complies with international law and Palestinian rights. Horowitz believes that the hearings began necessary conversations on campus and, ultimately, to the establishment of a University chapter of JVP.

“It was pretty clear to me that there needed to be an organization that talked specifically about Jewish students’ relationship to this issue, because often times it’s harder for Jewish students to let go of things that they’ve been taught their whole life and realize the reality of the situation on the ground,” Horowitz said.

Passing the resolution was an important symbolic stance, but Horowitz has been disappointed by the WSA’s lack of enforcement of the ban.

“The passing of the resolution itself was pretty powerful, to say that the student body stands behind divestment,” she said. “The WSA is flawed as an organization because there’s no way to keep them accountable to the resolutions that they pass…and they know it. That’s been one of the challenges with divestment, is just getting people to follow through on things they commit to do.”

Although Berkman agreed with Horowitz that the proposition produced necessary dialogue on campus, she remarked that the discussions revealed a problematic dynamic.

“I think it was a big lesson to us at J Street and really eye-opening to understand the dynamics at that time,” she said. “It was also frustrating, because it was the end of the semester…and then it kind of dropped, and everyone leaves for break. I think you see that quite a bit on campus. These big issues rise up, there’s some sort of chaos around it, and the semester ends, and everyone goes home. Some people are left upset, while most people just forget.”

In November 2014, International House, Turath House, and the Bayit hosted the International Conflict Panel Discussion Series, attempting to continue that dialogue, among others. The first event in the series sought to involve members of Wesleyan United with Israel, J Street U, and SJP. However, Renetzky, the representative for Wes with Israel, was disappointed to learn that SJP had declined to participate.

“It was going to be awesome to show that these three groups can work together and talk about a really heated thing,” Renetzky said.

In March, SJP members elaborated on their decision in a Wespeak titled, “Israel’s Apartheid State,” in which they wrote:

“We believe that dialogue on this campus about Palestine/Israel should not be ‘normalizing’—meaning we should not accept Israeli state actions as ‘normal’ or appropriate.”

Horowitz commented on this issue of normalization.

“I think you can’t expect voices to be heard through dialogue, because that normalizes the occupation as a conflict as opposed to the occupation that is illegal of a land that doesn’t belong to Israel,” she said. “To expect to hear all of those voices when you sit down for dialogue isn’t going to happen.”

Instead, Horowitz proposes that people seek out these marginalized voices.

“People need to be educating themselves more to hear these voices, and going into spaces where they might be uncomfortable,” she said.

That panel was only one of a few incidents that contributed to unease between members of Wesleyan United wih Israel and SJP. In February, Wesleyan United with Israel hosted a free Israeli Late Night. Days before the event, an SJP member posted an article about Israel’s appropriation of Palestinian and North African cuisine to the Facebook event page.

“They also flyered outside our event saying, ‘The hummus is free, but Palestine isn’t,’” Sussman said.

According to Renetzky, posters that Wesleyan United with Israel had hung in Usdan to advertise for the event were vandalized. He was discouraged by the animosity that these attacks revealed.

“They crossed out ‘Israeli’ and wrote ‘Palestine,’” Renetzky said. “Then they crossed out ‘Israeli’ and wrote ‘Fascism.’”

Sussman was also upset by the vandalism, which she believes limited the group’s ability to express its aims.

“While we believe so vehemently that everyone should feel comfortable voicing their opinion…and I totally believe that SJP should exist…I just think it’s sad that they don’t seem to feel the same way, when I really consider that so important,” she said.

Alpert believes that the vandalism incident is suggestive of more widespread animosity towards Wesleyan United with Israel.

“The fact that we can’t hold an event celebrating the culture—just the culture; we were not defending any of Israel’s military actions—we think is problematic on this campus,” she said.

Horowitz explained that protesters handed out flyers because of the difficulty of disentangling Israeli culture from politics.

“You can’t separate Israeli culture from what’s happening there,” she said. “I think Wes with Israel is a political group, and to get people to come to celebrate the culture and not own up to the politics being espoused is not an honest way to talk about culture.”

The Wall as a Metaphor

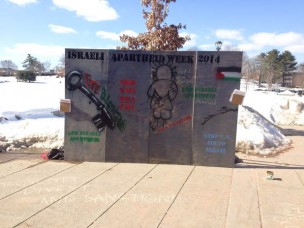

Israeli Apartheid Week is an annual, international series of events that, according to its website, aims to raise awareness of Israel’s apartheid policies toward Palestinians and to build support for the BDS movement. In early March, members of SJP collaborated on the aforementioned Wespeak, “Israel’s Apartheid State,” to explain its decision to erect a portable wall, which stood in various locations including Olin Library and Usdan.

“In the words of Wesleyan United with Israel, ‘You are going to hear a lot in the coming weeks. You are going to hear that Israel is an apartheid state,’” the Wespeak reads. “This accusation is part of the message of Apartheid Week, a university-based movement that seeks to raise awareness about Israel’s apartheid policies towards the Palestinians.”

SJP’s Wespeak referenced another Wespeak that the Wesleyan United with Israel founders had published two weeks prior, titled “Apartheid and Genocide in the Middle East,” in which they contested the usage of words such as “apartheid” and “genocide.”

“We think those words misrepresent the situation,” Greenberg said.

Renetzky was unsettled by the wall and the words spray-painted on it, which included “End Israeli apartheid” and “WALL WALL WALL.”

“I’m really upset by it,” he said. “‘Genocide’ is such a loaded word. There’s been genocide in Uganda; there’s been the Armenian genocide; there’s been the Holocaust. To call what’s happening in Israel genocide is wrong. It delegitimizes and minimizes so many terrible things that have happened in the world and are happening in the world.”

SJP’s Wespeak explains that its members chose to include the word “apartheid” intentionally.

“The word ‘apartheid’ does carry a lot of weight,” the article reads. “In the case of Israel, it represents many of the realities for Palestinians living under illegal Israeli occupation, and although the situation in Israel/Palestine is not identical to that of South African Apartheid, this vocabulary provides us with a means of understanding the occupation and the wars on Gaza.”

Renetzky, however, maintains that the portable wall does not tell the full story.

“They put up this big concrete wall in Usdan, in Olin, wherever,” he said. “They’ll tell you, ‘It’s this long, it’s this big, these are the 10 reasons that it’s oppressive.’ What they’re not going to tell you is that 90 percent of that wall is chain-link fence. It’s not all huge concrete barriers with watch towers. And what they’re especially not going to tell you why that wall is in place. In some areas, there were people from within the West Bank, snipers, who were shooting at Israeli citizens. So in response to these snipers, Israel built up a security, protection wall. So, wall goes down, who’s to say snipers don’t come back?”

Renetzky believes that not telling the full story allows SJP to more easily rally support more easily.

“It’s so easy to be like, ‘Sign this petition!’” he said. “‘It’s for human rights.’ But…my mother’s Israeli…and I have a lot of family who lives there as well. I hear the narrative of, ‘This is my life, this is my country, there are missiles being fired at me all the time, and we need these things.’”

According to Horowitz, however, the point of the wall is to generate horror and discomfort.

“The wall is a really powerful educational tool because it shocks people and it makes people uncomfortable in a way that is going to make them search for more information,” she said. “It is nothing more than a fact that [the] wall exists, and the realities of that wall exist, and so it’s really hard for people to disagree with the wall. It’s a representation of something that is happening in our world.”

Future Visions, Conversations

Despite the tension that has surfaced, leaders of the groups who were interviewed are optimistic about the degree of engagement on campus.

“I think that having [Wesleyan United with Israel] on campus enriches the dialogue even for people who don’t agree,” Greenberg said. “There are a lot of people who came up to us and said, ‘I’m part of J Street, and I don’t align with you politically, and I think this is great. And I think it’s great that you’re doing this.’”

For Greenberg, continued engagement is a goal in and of itself.

“I hope that people continue to engage with us, not necessarily that we change their political beliefs,” she said. “I engaged with a lot of different groups and formulated my beliefs, which was really cool. I think that going forward, we want people to know that we exist, that we are approachable, and we want dialogue. We want people who have pro-Israel beliefs to feel comfortable saying that, but we also want them to say, ‘But I don’t agree with this one thing [Israel] did.’”

University President Michael Roth said that he appreciates the diversity of opinions on campus, advocating for a high level of discourse among students.

“Oy vey!” Roth said. “I think that trying to understand the issues in that conflict, and how one might be able to have an impact on American policy or what goes on there, is a really good question to ask oneself. Raising the intellectual level of understanding about the issues of the occupation, of the dynamic of violence and war in the region, Israel’s security concerns, and human rights issues—there’s a whole range of things to think about, that people are politely and intellectually disagreeing about.”

Roth aims to foster an atmosphere in which students can engage with this issue safely and deeply.

“I see my role as president, as opposed to…just a citizen, is to help the dynamic of sometimes intense, sometimes conflictual conversation and debate, but also to make sure that people don’t feel threatened, that they have some protection if things get too intense, that they’re not going to be ostracized, and they’re certainly not physically at risk,” Roth said. “I’m proud of the community that people can debate vigorously, but stay in the world of discourse rather than violence.”

University Jewish Chaplain Rabbi David Leipziger Teva noted that this issue is especially contentious because it affects many students personally and ethically. Like Roth, he advocates for inclusivity and open-mindedness.

“We should all keep in mind that students who are active in the various Israel/Palestine groups on campus are often motivated by ethical values of justice and human rights as well as from personal identification with a geographical place that is close to their hearts and the hearts of their ancestors,” Teva said. “Our challenge is to create intellectually sophisticated conversations where students can be exposed to alternative political narratives without being labeled or disempowered.”

There might be no conclusion or resolution, but Berkman is confident that students are capable of participating in increasingly constructive conversations.

Leave a Reply