“It Follows,” the new horror film directed by David Robert Mitchell, opens on a quiet suburban street. It’s a rare instance of peace in a film dedicated to rupturing one symbol of comfort and intimacy after another, though it does not last long. Soon, the door to one of the houses bursts open and out runs a young girl, wheeling around terrified as if to check for something behind her. There is nothing that we can see, but she becomes more and more frantic, only quieting herself to assure a puzzled neighbor that everything is alright. Soon, she dashes back to her house, jumps in her father’s car, and speeds off, leaving whatever had been hunting her behind on that stretch of pavement. When we next see her, she is huddled on a beach at night, shivering in the sour strip of light provided by the car’s high beams. She answers a call from her father and tearfully apologizes.

Then, she waits. In the morning, she is dead in the sand, limbs twisted at grotesque angles.

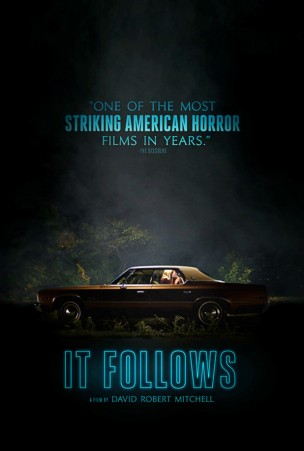

It’s a jarring and confident beginning for a film directed by a man whose only other feature-length project was a little seen coming of age drama released in 2010. Though fans of horror films—especially those from the 70s that Mitchell’s camera frequently cites—know that there’s something inherently insecure about suburban calm, “It Follows” manages to, over and over, find new registers of unease, tenderly establishing setting and character just to remind the audience to distrust that tenderness. It’s a sadistic give-and-take that the film engages in, but one that’s deeply rooted in the issues that Mitchell’s film seems most interested in investigating. Horror is about the perversion of those things that seem most dear or certain, and “It Follows” is a shining example of the impact available to directors who can do so well.

Combining trappings of both supernatural horror and the classic slasher film (as reshaped by John Carpenter in 1980’s “Halloween,” building off the experiments of films like “Peeping Tom,” “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” and “Black Christmas”), “It Follows” presents its audience with a simple premise that it proceeds to deepen and personalize without ever demystifying. The picture stars Maika Monroe (of Adam Wingard’s phenomenal “The Guest”) as Jay, a college student living in the suburbs of Detroit. One evening, Jay goes out to the movies with her new boyfriend, Hugh, who seems unusually jittery, something that Jay attributes to his growing impatience with their slowly materializing sex life. The next time they see each other, they have sex in Hugh’s car in the parking lot of a hulking abandoned factory. It’s tender, if clumsy, and in the moments following, Jay lies prone across the back seat of the vehicle, batting at the weeds and flowers that have poked through the fracturing tarmac. As Hugh steps outside, she explains how she once thought dating would be, laughing at the simplicity of her old notions with a sort of wistfulness. Next thing she knows, Hugh has climbed into the car next to her, where he proceeds to cover her mouth with a chloroform soaked rag.

Jay awakens strapped to a wheelchair inside the ruins of the factory, with Hugh nervously pacing behind her. He promises her that he has no plans to hurt her, but simply needs to explain something that he fears she would ignore under less extreme circumstances. He has been cursed, Hugh explains, and by having sex with Jay he has transferred the curse to her. Until she does the same to another she will be perpetually followed by an unknown entity, visible only to her. It will stalk her day and night, but always at a walking pace. It will take the form of those she loves, or strangers in a crowd, anything to get close to her. If it catches her, it will kill her, and then come back for Hugh, slowly moving back down the line to the originator. Wheeling Jay over to one of the blown out windows, Hugh points down to the lot outside where Jay can now see the figure of a naked woman, slowly walking towards the factory. Hugh reiterates, this is no joke. For the remainder of the film, Jay and her friends must contend with the Follower in its various iterations as it hunts Jay across the state. Toying with the glacial pace of the archetypal slasher, Mitchell imbues the creature with a strange existential grotesquerie: it may move slowly, but it will not stop. Unless you are willing to pass the fate onto someone else, this thing—whatever it is—will certainly outlast you.

Mitchell is painstaking in his dedication to the paranoia inherent to the premise. The permutations of the Follower are wickedly clever, moving as hungry, visceral symbols through the world of the film. The camera—which alternatingly creeps and charges through sets and landscapes—becomes one more tool to demarcate the incremental approach of the creature. In a particularly masterful scene, Mitchell crafts a panorama in the hallway of a school-building, tracking the ever-closer Follower with each rotation of the shot. Carefully juggling the washed-out palette of classic genre pictures with splashes of intense color, Mitchell creates a sense of wicked imbalance. The once energizing appeal of intimacy is now a marker of encroaching danger. Furthermore, unlike pictures such as “Species” or “Shivers,” which locate the terrors of sex in the effect it will have on the protagonist, “It Follows” pinpoints that anxiety in the figure of the partner, to whom sex will transfer the violence of the curse.

Much has been made of the film’s allegorical interest, and appropriately so. While sexuality is not a new interest of the horror genre (the slasher films Mitchell often references have long held that if you have sex, you die), the current landscape of sexual discourse is ostensibly much different than it has been at any other point. Coming out around the same time as campus-rape documentary “The Hunting Ground,” “It Follows” is keenly aware of how its set-up emulates the anxiety and outrage that comes with any real acknowledgment of sexual violence. At various points in the film, conversations among characters (and even the shape of the Follower itself) make reference to the possibilities of violation and exploitation. The image of Jay tied in her underwear to a wheelchair that has played in nearly every trailer is a conscious gesture toward this as well.

But while critics have argued over whether the film is an allegory for sexual assault or sexually transmitted diseases (and there are images in the film that can be read variously as either), it’s more likely that Mitchell isn’t interested in restricting his film to the one-to-one relation that can make or break allegorical genre films. At its core, “It Follows” is an investigation of trauma, both large and small. On the macro level, it presents its audience with a protagonist who, after a disturbing sexual encounter, is followed by a manifestation of that encounter that only she can see. Jay’s fear, so often inexplicable to her friends, seems to cast the Follower as PTSD given bodily form. Anticipating its approach, Jay demands that her friends stay over at her house, and at one point stares at her body in the mirror with a tangible self-hatred.

Less explicitly, though, “It Follows” also works to diagram the micro-traumas that come with growing up: the uncovering of lies told and responsibilities ignored; the realization that maybe you were let down without even knowing it. Much like in the films it references, Mitchell’s picture has a curious lack of adults. Whereas in lesser films, this omission just seems to be a facilitator of chaos, for Mitchell it is a central notion. Jay’s mother is glimpsed only once, sprawled out on her bed with a glass of wine, an empty bottle, and a still-lit cigarette adorning her dresser. When the Follower lays siege to her home, Jay begs her friends not to wake her mother. “She won’t believe me,” she explains. Later in the film, as Jay and company attempt to lure the creature away from their neighborhood, they reminisce about the geographic boundaries their parents imposed. “I wasn’t allowed to go past 8 Mile,” one recounts. “It Follows” presents a world of superficial and deeply rooted restrictions that both illuminate and obfuscate the dangers against which they are meant to protect.

“It Follows” is a terrifying thrill of a film: smart, funny, tender, and engaged with its characters and world in a way that few films of any genre are. It has a sense of history and context, but invokes both without suffocating the originality of its premise and vision. Packed with sharp and understated performances, chill-inducing and memorable set-pieces, and wickedly attuned direction from Mitchell, the film plows forward without sacrificing pacing or quality, satisfyingly fulfilling its generic obligations while reaching outside those confines to engage universal ideas. Though its ending flags a bit—as is often the case in supernatural horror films when the antagonizing force must be confronted—the few minor missteps are easily overwhelmed by the myriad pleasures the picture offers. “It Follows” is horror stripped to its bare bones; it is a dynamic, pitiless, gleeful beast of a movie. It reminds its viewer that the things that are frightening are so because of their elemental, indiscriminate existence. It reminds us that horror is human, even when it’s not.

Leave a Reply