When critics talk about the Mountain Goats, they usually cite those albums on which John Darnielle’s neo-folk outfit sounds most dour: The Sunset Tree’s taxonomy of child abuse and domestic terror, the disintegrating marriage dissected on Tallahassee, the encyclopedia of drug addiction that is We Shall All Be Healed. Even those records on which Darnielle appears most optimistic seem to draw on a deep well of unrest. Heretic Pride—which Pitchfork noted as one of the happier Mountain Goats records—takes its title from a track on which the singer’s ultimate triumph is being burned at the stake. On that same record, the song “Autoclave” presents the comforting fantasy of being “perched atop a throne of human skulls.” Triumph, it seems for Darnielle, is a lesion in and of itself.

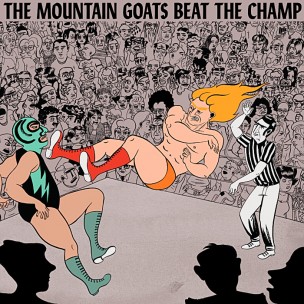

Beat the Champ, Darnielle and company’s latest album, may be puzzling to some. As a record focused entirely on professional wrestling (primarily in the 1970s and early 1980s), the LP might seem like an odd companion to other Mountain Goats works, which often combine harrowing intimacy with grand, almost mythological themes. But while potentially being the most idiosyncratic and most divisive of the band’s albums, Beat the Champ actually fits neatly into the Darnielle canon. The songwriter, who recently published a novel focused on the workings of a by-mail fantasy role playing game, has a somewhat well documented history of incorporating his niche interests into his music; it’s what gives the Mountain Goats’ folk its seemingly peculiar fascination with heavy metal. Furthermore, Beat the Champ is perhaps the best opportunity for Darnielle’s songwriting to bridge the gap between the personal and the universal, deftly translating themes of loss, frustration, identity, and justice into the vernacular of the wrestling ring in which he can then examine them under that world’s harsh, brutal, theatrical, and invigorating light.

In many ways, one doesn’t really need to know anything about professional wrestling to partake in the pleasures of Beat the Champ. At its core, the record seems certain that every posture and gesture and finishing move that shakes the ground inside the ropes is detectable in some form in the world most familiar to the average person. The record’s second single, “Heel Turn 2” may be the strongest example of this. Framed as the story of a heroic wrestling character making the performative shift to villainy, the track ultimately becomes a bitter ode to self-compromise and vindication akin to The Sunset Tree’s “Up the Wolves.” “Spent too much of my life/trying to play fair/Throw my better self overboard/Shoot him when he comes up for air,” Darnielle sings; “Come unhinged/Get revenge/I don’t wanna die in here.”

A good deal of the album digs into the roster of professional wrestling, juxtaposing the exploits of specific titans with Darnielle’s own past. On “The Legend of Chavo Guerrero,” Darnielle compares the career of the titular Mexican wrestler with the singer’s own troubled relationship with his father. Guerrero’s father trains him as a wrestler and offers him access to a family legacy; Darnielle’s intentionally cheers for the fighters his son despises. Those staged matches on TV become a personal struggle for Darnielle (“I need justice in my life/Here it comes”). Alternatively, the spoken-word “Stabbed to Death Outside San Juan” dramatizes the murder of the Bruiser Brody in a mercilessly textural first person (“When the blade hits the bone everybody hears it sing”), omitting Darnielle completely. Regardless of his own closeness to the subject, however, Darnielle showcases his characteristically fearless empathy, refusing to treat any experience as insignificant. Hell, “Unmasked!” turns the unmasking of a defeated fighter into a sort of spiritual flaying.

That Beat the Champ is able to, so unpretentiously, make meaning from what many might consider an exceptionally frivolous topic is a testament to the record’s total commitment and sincerity. Darnielle is keenly aware of the blood and sweat that makes the matches he loved so mesmerizing, and he treats the manufactured drama of the ring as something almost sacred. “Werewolf Gimmick,” a rollicking tempest of a track, makes the mere act of getting into character seem as consuming an experience as preparing for some sort of life or death combat. “Foreign Object,” an album highlight that produces a chorus equal to “hail Satan” from “The Best Ever Death Metal Band in Denton” in terms of bizarre emotional impact, is a jazzy horn-driven celebration of the boastful in-ring speech.

Moreso than many other lyricists, Darnielle seems to revel in the specificities of language, searching out and deploying casually arcane metaphors (“The sky goes dark and there I am/Climbing down the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram”), and savoring the weight of names and phrases. Even those references that feel obscure seem to carry a charge. The names of specific fighters gesture towards a mythological expanse—a gleeful spandex pantheon, if you will—and designations of signature moves become unabashedly onomatopoetic. At times, Darnielle’s refusal to explain anything leaves the listener feeling as though they’ve walked into a film midway through. For some, this might be frustrating. But Beat the Champ excels at making the disorientation fruitful. Soon, the nature of the details fade away and leave the listener to simply marvel at the sound and action; the violence, tenderness, and anxiety that somehow breeds investment even stripped of context.

Though it isn’t quite as accessible as previous Mountain Goats records, Beat the Champ is a masterful demonstration of the group’s versatility and Darnielle’s seemingly boundless creativity as a writer. Despite the insular subject matter, the album feels like one of the band’s most emotionally complete offerings, moving gracefully between tones and registers, carving out an immensely intricate universe within the confines of its restricted territory. It’s doubtful that Beat the Champ will transform any listeners into wrestling fans, but then again it doesn’t seem to care much about that. On one level, the LP seems to argue that Darnielle’s fandom is just one specific permutation of a set of fundamental cravings. Even at its most alien, the record feels a great deal like listening to a friend talk excitedly about an interest of theirs. Sure, the jargon may create a distance, but the shameless passion for the thing is more than enough to bridge that gap. I doubt I’ve ever watched an entire WWE special. But I would happily pay the cable fee just to have John Darnielle narrate one to me: heel turns, Tombstone Piledrivers, People’s Elbows, and all.

Leave a Reply