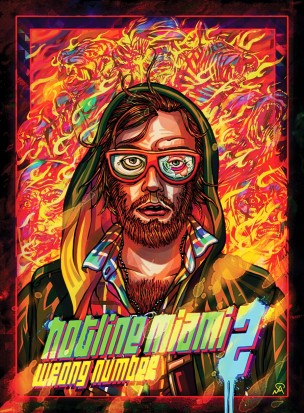

c/o iam8bit.com

The original “Hotline Miami” was a pretty strange game. Created by Dennaton Games, a two-man development team, it felt like someone took the collective filmography of Brian DePalma, Terry Gilliam, and David Lynch and distilled it all into an ultra-violent, 2D beat-em-up.

In the years since its release, the game became kind of a hero within the indie game movement, earning rave reviews and high sales, and with the open ending of the original, a sequel was in high demand. In pure technical terms, “Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number” succeeds in building upon the achievements of its predecessor. However, one can’t play the game without noticing that its creators seem intent on raising a question that’s both provocative, and a little problematic, about video games as an artistic medium.

The original “Hotline Miami” told a hallucinatory neo-noir story about a masked vigilante brutally taking out Russian mobsters at the behest of a mysterious group of benefactors. “Wrong Number” is a little more ambitious with its storytelling, putting the player in the role of 12 protagonists as the narrative jumps back and forth in a weird alternate timeline. The Fans, a group of four bored slackers, provide the main drive of the story as they attempt to copy the vigilante killings of the original game. Other sections will put the player in control of a detective, a journalist, a mafia hitman, a soldier during an American-Soviet conflict, and an actor starring in a shlocky ’80s slasher movie recreating the original game. These plotlines all intersect and interrupt each other in a way that’s messy, but nevertheless incredibly satisfying.

Regardless of which character one plays as, the concept of every level is the same: the floor is full of armed thugs who want you dead, so it’s kill or be killed. Much like its predecessor, “Wrong Number” is unforgiving in its difficulty. This is a game where a single bullet or strike with a baseball bat can take you out, meaning that gameplay requires a mix of stealth and split-second improvisation. Each level will mean dozens of deaths, but then the game just restarts, keeping things at a tight pace. Eventually when, after countless failed attempts, one memorizes the enemy patterns and figures out the perfect weapon combination to take down the last thug, the sense of achievement is monumental.

One of the ways “Wrong Number” outdoes its predecessor is in the variety of ways a potential problem can be tackled. If you’re playing as the Fans, for example, you can choose to play as Corey, who’s dodge ability leads to dynamic flowing gameplay, or Tony, whose lethal punches require a more careful approach. The levels starring the Journalist, who is non-lethal in his methods, require much more care and finesse. Meanwhile, the levels you play simultaneously control the twins Alex and Ash, respectively equipped with a gun and a chainsaw, invite pure balls-to-the-wall insanity.

As you might have guessed, “Wrong Number” is a very violent game. Even though the top-down perspective uses a pixelated, super-low detail style, there’s definitely a moment of shock when the player realizes the takedown for a fallen enemy may require literally stomping their head in. That said, the shock of the blood and gore is dimmed a bit by the bright flash of the game’s ’80s neon style. It’s so dedicated to its retro mystique that the pause menu even subjects the screen to the same scrambly lines you used to get when you paused a VHS cassette. The aesthetic is also aided by the game’s soundtrack, a collection of pulsing synth-heavy beats that would be well at home within a Carpenter flick, or just about anything staring Kurt Russell or Dolph Lundgren.

And yet, as much as the game achieves technically, one can’t in good conscience recommend it without acknowledging the elephant in the room. Before its release, the game received a lot of criticism and was even refused classification in Australia due to its depiction of sexual violence.

The scene in question occurs during the first level of the game. With no sense of context you fight your way through a room full of people. Then, without any control from the player, your character begins to sexually assault a woman, before a director off screen yells “cut,” and everyone stops what they were doing. It turns out that the segment you’ve just played was only a series of actors, acting in a movie loosely based off the events of the previous game. And yet, in spite of this twist, you can’t undo what you’ve experienced.

To be fair, this choice of opening does serve a purpose. “Wrong Number” is a game that likes to question where the player will draw the line in a pixelated setting, usually by constantly making them cross that line. The game is totally aware of the fact that—by virtue of its heavily pixelated aesthetic and the abstraction that it suggests—it merely needs to dress its AI characters in white suits and tell you that they’re mobsters for you to feel like the game’s brutal acts are justifiable. The moments when the characters act outside of the players’ control, however, the game usually succeeds in completely stripping them of their allegiances. As gaming progresses into the current generation and slowly reaches a stage where it could be considered an art form, it is important to consider the issue of limits that “Wrong Number” makes us confront. Personally, though, I don’t think they needed to go to such nasty lengths to make a point.

Play the game, think about what it has to say, but take the option of skipping the opening scene.