There are a number of ways we experience celebrity deaths. Sometimes we find ourselves fiercely personally moved by the loss, as I was last year with Philip Seymour Hoffman and this summer with Robin Williams. Perhaps this is because their work or their personae were deeply ingrained in us over the years. If we buy that art can shape who we are, than in those cases it feels like we’re losing a part of ourselves. In other cases, the mourning seems to come from a place of respect more than anything else, an understanding of the role the deceased played in culture, perhaps an implicit unspoken understanding that this person might have played the deep, piercing, definitive role in someone else’s life that they never played in ours. For years, I greatly admired the work of Mike Nichols (director of “The Graduate,” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf”), but when he passed in November, the hurt felt somewhat removed: a melancholy knowing that a family had lost someone whom they loved, and that cinema had lost a great and lively voice.

On Friday, when I awoke to hear that Leonard Nimoy had passed away in his home in Bel-Air, I experienced something between the two. Nimoy was a towering cultural figure whose work as Mr. Spock in Gene Roddenberry’s original “Star Trek” television series and its cinematic extensions made him one of the most widely recognizable icons of science fiction. As Nimoy grew older, he alternated between shunning and accepting the import of the role, publishing two separate autobiographies: “I Am Not Spock” (1975) and “I Am Spock” (1995). Later in life, Nimoy made appearances in both of J.J. Abrams’ rebooted “Trek” films (as an older version of the character he originated) and as a regular on “Fringe” (a twisting, at times marvelous television show co-created by Abrams, Alex Kurtzman, and Roberto Orci) as Dr. William Bell. Both of those roles were haunted by his work as Spock, as though Abrams was dedicated to somehow capturing and repurposing the sonorous dignity that Nimoy had emanated alongside William Shatner and crew. Whereas in most situations this might seem lazy or cheap, Nimoy made it work. Even as he ran through some of Abrams’ more ponderous dialogue opposite Zachary Quinto, he seemed joyous and generous. It was thrilling to see him, though he was never reclusive, and it seemed like he was thrilled to be there, even as he coached Chris Pine through the droning guidelines of time travel, buried under furs in a space somewhere off in unimaginable distance.

I cannot claim to have been a “Star Trek” devotee, nor a longtime fan. As a child, I was all Star Wars, all the time, and I don’t think I even figured out what “Trek” was until late in elementary school. After that, I would watch it casually when it was on, but never obsessively. I enjoyed the show and its quirky old-school progressiveness. I laughed at the of-the-time effects. But I was never wholly enthralled, not in the way that some of my friends were. Still, somehow, when Nimoy passed away at 83 this weekend, I found myself startlingly broken up. It was inexplicable, but it somehow felt right.

To reduce Nimoy to Mr. Spock would be unfair. It’s clearly something that he spent time hoping to avoid. In addition to his television and film work, Nimoy wrote poetry and undertook photography projects; two of his series, “The Full Body Project” and “Secret Selves,” are rapturous in their compassion for and celebration of their subjects. He also released a number of albums, some of which touched on his “Star Trek” work, but many of which explored new terrain. Still, in all of the obituaries I have read, and in all of my own musings, I find the current returning to that one role. It’s been especially strange, since I most likely watched “Fringe” more religiously than I did “Trek” for a period. But there was something about how Nimoy punctured the cultural consciousness during those three years (and in the five films to follow) that has made that performance endure.

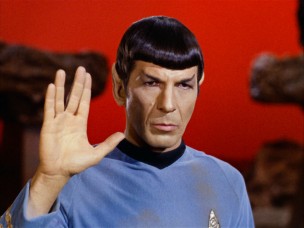

Part of me believes that it was simply a symmetry of actor and part, that Nimoy already embodied much of the solemn, dutiful manner of his Vulcan stand-in to the degree that it was all too easy to transpose one onto the other after the fact. Perhaps that’s the case, but that seems far too detached. Ultimately, it seems that Nimoy was never less than the warm and generous man he showed himself to be in interviews and in the musings of his Twitter feed, someone whose big-heartedness so filled his work on “Star Trek” that it’s hard not to want to revisit that moment when we first met Nimoy. Much in the way that you remember the first time you spoke to a friend or the first time you kissed a partner, it’s hard not to get a little giddy about the first time you heard that Vulcan mantra and saw that characteristic finger spread.

There was something so unabashedly open and shamelessly connective about Nimoy and his work. Watching it for the first time, I remembered feeling as though what I was seeing was somehow both more and less than fantasy. Of course, reading about the show’s history, it’s easy to see how the program took on the present issues of the day, using the futurist-liberal bent of its ideology to speak out on things like racism, classism, and gender politics.

More so than all of that, though, I found myself struck by how little artifice the show seemed to put up. Shatner’s bluster, George Takei’s energy, it all felt unrehearsed. Going back to watch episodes over the past few days has been hard, but also fulfilling. Seeing Nimoy so alive and so comfortable on the screen is cathartic. Watching how he brings the world around him to life is magical. I won’t be the first person to end my remembrance on a quote. Rather than “Live long and prosper,” though, I look to my personal favorite piece of Trek lore, which Nimoy characteristically brought out of the realm of fantasy and into my cynical heart: “Of all the souls I have encountered in my travels, his was the most human.”

Leave a Reply