J.C. Chandor’s “A Most Violent Year” opens on a highway robbery: a young man torn from the cab of an oil tanker, as he’s stopped just past a toll on the 59th Street Bridge. The scene does not sneak up on the audience. In the man’s mirror, we see the two cars halt in front. We see their doors swing open and their drivers spin out, hardly trying to conceal the weapons that they brandish. Julian, the driver of the truck, has a boyish face, ringed with curly black hair that fades into uneven stubble on his cheeks and chin, and when the butt of a pistol shatters the passenger window of his cab, his eyes bug with confused terror. He is beaten viciously and left on the road, writhing on the barren tarmac as the supports of the bridge rise up behind him.

Like nearly everything else in “A Most Violent Year,” there’s a stark beauty to this scene. Intercut with slow panning shots of the fuel oil terminal on the East River pimpled with rusting tankers and serpentine pipes, it sets the stage for all that’s to come. It makes promises that Chandor will deftly fulfill, and it introduces us to the kind of story about to be told. Whether or not that’s clear in those opening moments, by the end of “Year,” it seems as though everything in orbit was created in the tumult of the first five minutes.

This is not to say that the latest from Chandor (who directed “Margin Call” and last year’s “All is Lost”) is an especially violent film, no matter what its title would suggest. “A Most Violent Year” is certainly a brutal film—filled with harsh acts and nary a sympathetic character—but rarely does it feel excessive or even especially sadistic. Rather the whole film seems to exist in the moments leading up to, and following, the attacks that propel much of the action, even as many of those assaults play out explicitly on the screen. There is a late afternoon pallor to each and every shot, something autumnal and forlorn. As characters edge across lots and industrial parks dusted with snow, the film threatens to snuff the light out of the world at any moment. Even in well-lit, comfortable rooms, the oranges and yellows of Chandor’s pallet seem impossibly tenuous, like the brightest points of a sunset that seem to already be fading just as they erupt into view.

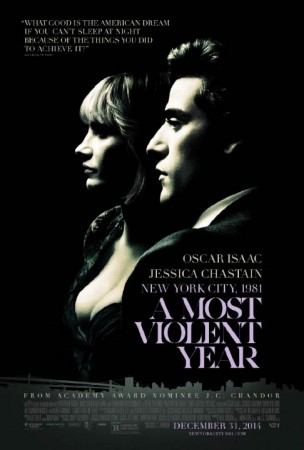

It’s the perfect aesthetic for a film such as this, which moves deliberately through a story that, at first glance, might seem less than thrilling. Manhattan and its surrounding boroughs in 1981 are in the grips of a seemingly inexhaustible wave of violent crime. Abel Morales (played by Oscar Isaac in yet another understated and earth-shattering performance), the owner of Standard Oil, suffers a series of muggings of his drivers. A truck bearing roughly $6,000 of product is stopped, the driver assaulted, the oil stolen. The truck will later be found completely drained, with no way to tell who was responsible. Abel’s wife Anna (a devastating Jessica Chastain, who threatens to steal a good portion of Isaac’s scenes through sheer force of will) believes that this violence will soon be targeted at the Morales family itself, and urges Abel to fight back. The head of the Teamsters demands that Abel arm his drivers, or they will quit. Compounding this, Morales has 30 days to acquire $1.5 million to close a business deal on the East River oil terminal, and a D.A. (David Oyelowo) has just informed him that charges are being brought against Standard.

A story of business ethics in the oil business may not be the easiest to sell, but to “A Most Violent Year’s” credit, Chandor never acts as though he should have to. Instead, he lets the picture unfold, moving gracefully from scene to scene with incredible precision and letting the film grow before the camera. The film’s script does a magnificent job of preserving order among the many characters and plot threads, assuring that the story never stumbles over itself, and even in the moments when the pace slows, “Year” never drags. It’s a fantastically tight movie, drawing tension and momentum from every corner of the shot every line of dialogue. In offices and cars, Chandor seizes on the smallest details: the radio, haunted with the promise of further reports of violence against drivers, for example, or Abel’s long runs through the woods and down by shipping yards.

Many critics compared Chandor’s film to the work of Sidney Lumet, and the comparison is undeniably apt. Isaac’s performance recalls the quiet intensity of Pacino in “Serpico,” and Chandor’s attention to environment and texture invokes a similar New York to the one that fueled many of Lumet’s best pictures. But, even more than stylistic concerns, it’s the themes of Lumet’s filmmaking that seem to most fuel the more powerful aspects of “A Most Violent Year.” For Chandor, New York is an organism designed to produce a certain sense of Americanism, that then spills out of the city into the surrounding terrain. As a disciple of that spirit, Abel Morales prides himself on his hard work, his clear conscience, and his refusal to bow to pressure. Even as the world around him curdles to reveal the fantasy of those beliefs, he holds to the sense that something, somewhere has destined his success and has promised him his oil terminal with its view of the Manhattan skyline. So, when Morales goes to confront the sister of an assaulted driver, demanding that she turn her brother in to the police or when he snarls at Chastain, accusing her of undermining his hard work and endangering their family, the performances are tinged with something especially haunting, drawn out by the world of the film. “I promised myself I’d never become a gangster,” Abel intones. But like Lumet might, Chandor takes little time to bask in that sort of integrity. Has Morales even succeeded, he asks, or is that sort of hope and purity just impossible in the American struggle to survive?

This is not a new idea, and it isn’t even especially rare for 2014’s films. In many ways, Bennett Miller’s “Foxcatcher” wrestled with similar themes: the sense of American prosperity and failure in the 1980s; the integrity of the American Dream. But where Miller’s film is content to live out its runtime in halls decorated with flags and eagles and the gunnery of wars long won, “A Most Violent Year” holds back. We never really spend any time in Manhattan proper, nor do we ever get to see those things that Abel is so certain of. Whereas Miller’s characters have the chance to wear the American colors as they train to represent their country in the Olympics, Chandor’s are left to fight for the rusted metal and deep black crude that they’ve staked their fortunes on. These are the tokens of prosperity that Abel Morales and his family have to defend.

“A Most Violent Year” manages to be a great number of things, each with more grace and conviction than some films that simply settle for one. It is a gangster film devoid of gangsters. It is an American fable stripped of its morals. It is a character study, and a crime drama, and a business procedural. There is so much for the movie to present to viewers that even after two separate screenings I am still unpacking much of the picture’s nature. Had it been released earlier, it is nice to think that Chandor’s film would be a frontrunner for Best Picture. Unostentatious, diligent, powerful, and lucid, it would most certainly deserve it.

Leave a Reply