Over winter break, the weather outside was frightful. For the Features editors, however, these books were so delightful. Take a page out of our book and buy (or check out) these titles.

“i will never be beautiful enough to make us beautiful together” by Mira Gonzalez (2013)

Sharp and insightful, Gonzalez’s debut poetry collection describes feelings of alienation, depression, social anxiety, and self-loathing. Centered on the theme of loneliness, the collection precisely conveys the experience of being a young person in the Internet age. Gonzalez earnestly recounts uncomfortable sexual encounters, confesses to Adderall and Ambien binges, and wonders if porn stars feel sad. Gonzalez’s strongest poems are those in which she positions herself as an observer. In “untitled 5,” Gonzalez watches people interacting with one another at a party. “I wonder if anyone feels more lonely now than they felt an hour ago/when they were alone in their rooms looking at things on the Internet,” she writes. Funny, fresh, and articulate, Gonzalez’s impressions of her world resonate. Though at the collection’s core is a sense of inescapable isolation, readers will emerge from “i will never be beautiful enough to make us beautiful together” feeling a strong connection to the poet. —Rebecca Brill

“Humiliation” by Wayne Koestenbaum (2011)

Part cultural criticism and part memoir, “Humiliation” unpacks the universal experience of shame, exploring it from a range of historical, literary, and autobiographical angles. At the beginning of the book, Koestenbaum imagines humiliation as an “infernal waltz,” a triad consisting of a victim, an abuser, and a witness. As Koestenbaum works to convey the singular sensation of being humiliated, he applies this theory to instances including the abuse of young Michael Jackson by his father, Annie Leibovitz’s photography of Susan Sontag’s corpse, and his own sexual mortification in adolescence. Koestenbaum’s nuanced portrait of humiliation is striking in that it directly addresses a feeling that people tend to avoid. “Humiliation” spares readers no discomfort; in fact, reading it is an exercise in humiliation in and of itself. Readers become witnesses to a sequence of moments, each more shameful and cringe-inducing than the next. Koestenbaum’s examples, especially those derived from his own life (“Sitting beside a playwright, I began ejaculating, and at just that instant an urban planner walked into the room”), are painful to read, yet capture the human condition so perfectly that they are impossible to resist. —Rebecca Brill

“Anastasia’s Chosen Career” by Lois Lowry (1987)

Lowry, a genius by any account, published “Anastasia’s Chosen Career” in 1987 as part of the Anastasia Krupnik series, about a hyper-intelligent, often-bewildered pre-teen girl who lives in Cambridge, Mass., with her poet father, artist mother, and precocious younger brother Sam. In this installment of the “Anastasia” series, Anastasia receives a special assignment for her seventh-grade winter break: choose a career and interview someone in the field of said chosen career. It’s a no-brainer for the bookish, practical, Anastasia, obviously a future bookstore owner. But when she sees an advertisement for modeling classes, Anastasia realizes that even bookstore owners need a dose of confidence, glamor, and elegance. Throughout the week, Anastasia and her cohort of “models”—the silent, beautiful Helen Margaret; the sassy, confident Henrietta; the galoshes-wearing, nose-drop-inserting Robert Giannini—unearth their inner divas. Will Anastasia still want to be a bookstore owner after she learns to walk like a giraffe? —Jenny Davis

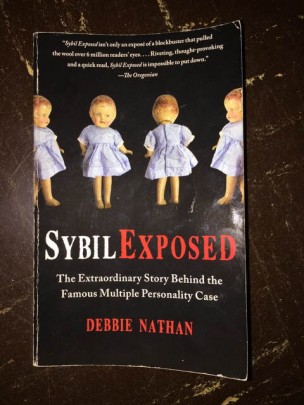

“Sybil Exposed” by Debbie Nathan (2011)

“Sybil,” the famous multiple personality case and the inspiration for a 1970s book and movie of the same name, was based on Shirley Mason, a shy, dreamy girl from rural Minnesota who grew up in the 1930s. After a series of nervous episodes, Mason was treated by Dr. Cornelia Wilbur, who went on to diagnose her with multiple personality disorder, publicize the disease, and spur the diagnoses of thousands of other patients, mostly women, throughout the 1960s and 1970s. “Sybil Exposed” focuses on the three women who created the “Sybil” franchise: Shirley Mason, Cornelia Wilbur, and Flora Schreiber, who penned “Sybil,” which was first passed off as a biography. In getting to the bottom of the “Sybil” story, author Nathan dwells on Wilbur’s unconventional, often unethical, practices, including the use of hallucinogenic barbiturates during therapy sessions. Nathan also addresses the possibility of Wilbur’s planting false memories in Shirley, aka Sybil. Nathan’s tale raises the question: Does what is now known as dissociative identity disorder (DID) exist at all? —Jenny Davis

“The Argonauts” by Maggie Nelson (2015)

In this experimental memoir to be published in May, Maggie Nelson ’94 offers rich insight into issues of femininity in today’s world. Rooted in feminist theory (scholars Judith Butler and Eve Sedgwick are among Nelson’s most cited sources), “The Argonauts” sheds light onto the complexities of sexuality, gender, language, and identity, even as it conveys the inherent limitations of such categorizations. The memoir revolves around Nelson’s relationship with the gender-fluid artist Harry Dodge. With wisdom, humor, and grace, she discusses the joys and challenges of raising a non-traditional family and her frustrations with cultural understandings of motherhood and marriage. Keep your eyes peeled for Wes-specific Easter eggs in this one, including a reference to chalking from the practice’s heyday. —Rebecca Brill

“My Name is Red” by Orhan Pamuk, trans. Erdag Göknar (2001)

During the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire experienced newfound influences from France and Venice, and as a result, art underwent a dramatic transformation. Embracing European realism, Turkish artists began to use shading and write their signatures on their work. Many Muslims were irate, declaring the new art an affront to their religion. Using a different character or piece of artwork as the narrator for each chapter—one chapter is “written” by a fake gold coin—Pamuk writes of an artist, Elegant Effendi, who has been murdered for his European-style painting. The novel enters with the dead Effendi speaking: “I am nothing but a corpse now, a body at the bottom of a well.” From there, the reader embarks on a quest to find the murderer, and to think about art: What is its purpose? Are great works really eternal? Why does style change? —Max Lee

“Inherent Vice” by Thomas Pynchon (2009)

Doc Sportello, a private investigator who spends more time smoking pot and imagining himself with women (whom he fails to pick up in real life) than he does actually investigating, is in charge of intercepting an alleged plan to capture the fortune of a real estate mogul, Mickey Wolfmann. From there, Pynchon takes the reader through a series of seemingly isolated twists and turns that in fact are not isolated at all: Every small thing is part of a larger conspiracy. Near the end, Pynchon tries to make the book about something bigger, too, in defining “inherent vice.” But the novel doesn’t seem interested; the joy comes from watching the scenes and the asides, often hilarious, occasionally painful. —Max Lee

“Old School” by Tobias Wolff (2003)

Although “Old School” has neither bewildered-looking teens nor creepy dolls on the cover, and thus is not generally my type of pleasure reading, it proved itself worthy of my undivided attention. Told in the frank, hilarious style of J.D. Salinger, “Old School” is the story of a boy who doesn’t quite fit in at his preppy New England boarding school. The year is 1960, and the school has invited a series of illustrious writers (including not-yet-dead Robert Frost and Ayn Rand, whose visit is nothing short of side-splitting) for whose attention the boys compete. The visits culminate with Ernest Hemingway, and our protagonist is desperate to win his audience; it’s a shame that practically everyone in this boarding school is a wannabe writer. The unnamed narrator (kind of a cliché, actually, but the device works in Wolff’s case) lifts a story from a literary magazine published by a girls’ boarding school and wins the competition to meet Hemingway. Will he be found out? Of course. Does he have any chance left of becoming a writer? You’ll see. —Jenny Davis

Leave a Reply