When I was 10 years old, I began my first summer as a saxophonist in the Renbrook Summer Adventure Jazz Band. The sax player who sat next to me was at least six years my senior and taunted me mercilessly every day. “You’re not gonna play a solo today? You’re not? Come on! That’s weak.” To prove him wrong, I spent days working on a short solo that I can still play today. Now, I am no great musician, but that doesn’t change the fact that this early torment was quite formative for me. Which is why I was floored by Damien Chazelle’s “Whiplash.”

In “Whiplash,” drummer Andrew Neyman (Miles Teller) finds himself in the premier jazz ensemble at the best music school in the country. The band’s conductor, Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons), is a perfectionist (verging on psychopath) who will do whatever it takes to get the exact sound he wants out of his band. Neyman pushes himself beyond his limits to be the drummer Fletcher wants.

It seems like a textbook inspirational teacher story à la “Dead Poet’s Society” and “Stand and Deliver,” but “Whiplash” does so much more. Chazelle’s film isn’t inspirational; it is pulverizing, from start to finish.

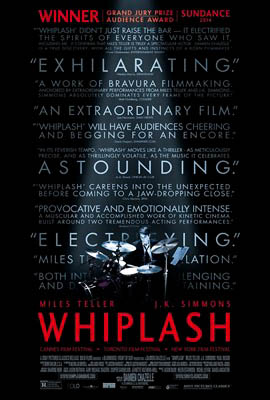

The film won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance this year, a decidedly earned accolade. The first scene alone is a masterpiece. The screen is black, and a slow snare beat fills in the space. The tempo picks up, faster, faster, faster, and the black gives way to a hallway shot of Teller playing the drums. Everything but Teller and the drum kit are pitch black. Suddenly he stops, and Simmons appears. His black shirt, pants, and blazer render only his expressive face visible. What follows is a brutal session that is as enthralling as it is intense. And the film only ramps up from there.

Critics have praised Simmons’s Fletcher as a force of nature, a monster that the film refuses to condemn. But he is so much more than that. Fletcher is disgusting, disturbing, magnetic, torturous. In his rehearsal room, Simmons hurls racist, homophobic, and generally repugnant insults like they are ammunition. Yet at the drop of a hat, he becomes a friendly jazz fan, the kind of person who ends all of his sentences with “man” and cries when hearing the music of a talented, deceased former student. When Fletcher plays piano in a jazz quartet, his sensitivity and joy counterbalance the horrible and horrifying things he says and does. In 2014, cinema has not given us a monster more fascinating.

There’s not enough that can be said about Simmons’s performance, but Teller, who was excellent in last year’s “The Spectacular Now,” is just as incredible. Neyman’s obsessive need to push himself to become “one of the greats,” as he puts it, is all-consuming. There’s an earnestness and authenticity to the early moments that Neyman shares with his father (Paul Reiser) and to his brief love interest (Melissa Benoist), making the toxicity and intensity of what happens later much more powerful. The charm of Teller’s character belies barely contained rage. Just as the film won’t condemn its antagonist, neither will it praise its protagonist.

“Whiplash” is a fast-paced thriller masquerading as a music-drama. It’s a small-scale story told with huge stakes, knockout punches, and two of the year’s best performances. Watching it, I couldn’t help feeling like I was 10 years old again, sitting in my house, trying to show that older musician what I was capable of doing. Perhaps beauty requires brutality.

Leave a Reply