Despite a world of flashbacks and flash-forwards, "Lost" didn't lose itself in convolution.

Ten years ago ABC aired a pilot with a murderous smoke monster, a polar bear, and a lot of characters being very confused. That pilot was “Lost,” and it was so expensive that the executive who green-lighted it was subsequently fired. Six seasons later, it had become a behemoth of network television that was incredibly divisive amongst its viewers.

“Lost” premiered on Sept. 22, 2004, opening with the crash of Oceanic Flight 815 on an uncharted island. As the show uncovered the lives of the survivors before, during, and long after the crash, it quickly became apparent that all was not as it seemed. The Island was not entirely natural.

At its peak, the show boasted nearly 22 million viewers, a bombshell in favor of serialized television that triggered a push away from the procedural drama. Networks have since sought to find the next “Lost,” but none have really been successful. That’s not to say other shows haven’t successfully borrowed practices from “Lost”: flashbacks and flash-forwards in television have increased greatly in frequency the decade since.

The show’s tone, especially in its early seasons, was rooted in these flashbacks. Depending on which character the episode focused on, the genre could vary wildly. We could follow the past of a con artist, a reluctant Korean mafia enforcer, or a sad doctor who just wants to make things better. Ultimately each episode would switch between these flashbacks and the plot on the Island, furthering the mysteries and the characters solving them.

Though the show’s influence on television has been quite notable, its legacy has been marred by the memory of its later seasons. The convoluted time travel, its unyielding mythology, and its controversial ending have left bittersweet memories for some viewers.

However, “Lost” never got too convoluted. There was enough logic to the show’s world to keep suspension of disbelief. In fact, much of “Lost”’s appeal stems from its complex mysteries and questions that only lead to more questions.

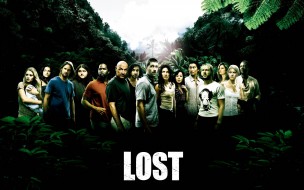

The underlying factor of “Lost’s” success comes less from its crazed setting and more from the strength of the cast that inhabited that world. When the show began, it boasted a record-sized ensemble. Of course, that cast included a few bad eggs (who the creators quickly killed off in creatively brutal ways), but also a surprising number of standouts.

Fascinatingly, fans (including myself) gravitated toward the ensemble characters more than the leads. Ben, the conniving and monstrous antagonist, is much more fun to watch than Jack, the series’ lead. Juliet, the often-unlikeable, confused double/triple agent, is much more engaging than Kate the outlaw. And then there’s Locke, the man of faith; Charlie, the drug addict guitarist; Hurley, the lovable lottery winner; Sun, an unhappy wife; and Desmond, the enigma. I could keep going. Several of the cast members (Michael Emerson, Terry O’Quinn, and Yunjin Kim, to name a few) took characters who could have easily fallen flat and instead made us want to watch them. And each of these characters had arcs that drastically changed as the series progressed and ensured we remained invested.

The early seasons eased us into the mysteries, and, in the beginning, there were only a few. “Is that a smoke monster?” “What the hell is that hatch doing there?” “Others?”

It was only after ensuring we fell in love with these characters that the show sank deeper into the maze. Many of the shows that have tried to copy “Lost”’s success and were quickly canceled have failed to realize this. The cast is more important than the mysteries. Fans who weren’t alienated by the mythos stayed because they loved to see these characters be just as confused as we were. And we got caught up in the mysteries because of them, not the other way around.

A common misconception is that J. J. Abrams ran the series. Though he was heavily involved in the series’ creation and helped with a few episodes, he actually had little influence after the pilot. Damon Lindelof (who has moved on to “The Leftovers”) and Carleton Cuse (who has now taken up residence at “Bates Motel”) made up the duumvirate for the show’s run.

Another part of “Lost” that isn’t discussed enough is its music. Michael Giacchino (who scored “Up” and all of Abrams’ movies until “Star Wars”) delivered my favorite soundtrack in television. He masterfully wove together motifs for each character, and when he wanted you to be emotional, you cried.

The show used popular music well. Season three opens to a semi-cheerful montage set to Petula Clark’s “Downtown,” which abruptly ends as characters look up to see a plane breaking apart overhead. The music is one of the reasons “Lost” is able to offer some of the best episode openings and closings in recent memory.

But then there’s the ending. Everyone talks about it. Yes, it’s not the show’s brightest moment. The “answers” given to some of the bigger questions seem shoehorned and lazy. Many questions aren’t answered at all. But the ending still works because, yet again, it all comes down to the characters. The final scene, amplified as usual by its soundtrack, offers an immensely satisfying conclusion to the show’s ensemble. It works, even in its vagueness. The final scene is, in a way, inevitable.

Ultimately “Lost” will be remembered in pop culture for becoming certifiably insane and having an unsatisfying conclusion. But there’s so much more to it than that. “Lost” was generally able to juggle a large array of interesting philosophical and thematic elements with its eclectic cast. And in a way it was network TV’s swan song. No network show has reached the benchmark of “Lost”, as AMC and HBO have taken the throne for quality television. And that in and of itself is a powerful legacy.