Annual Constitution Day Lecture Addresses Student First Amendment Rights

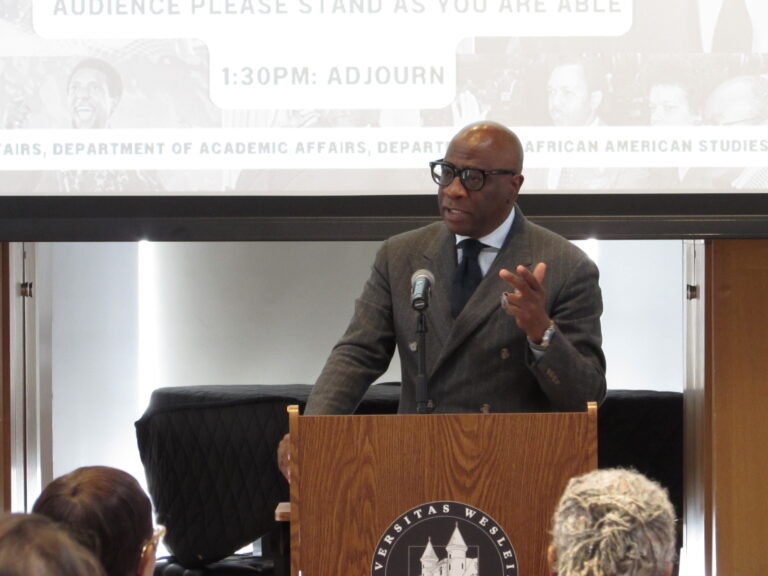

In honor of Constitution Day on Wednesday, Sept. 17, University of Texas at Austin School of Law Distinguished Teaching Professor David Rabban ’71 gave a lecture at Olin Library titled “Free Speech, Academic Freedom, and the American University.” The Friends of the Wesleyan Library sponsored the lecture, with Library Assistant Jennifer Hadley spearheading the event’s organization.

The talk centered on the First Amendment rights of students, professors, and universities as institutions. Rabban led the audience through the history of legal cases on free speech and academic freedom from the 1950s.

Rabban addressed the hotbed issues surrounding the First Amendment today. He allotted a significant amount of time to the recent case of Professor Steven Salaita’s lack of consideration for a job at the University of Illinois following several anti-Israel posts on his Twitter account.

Furthermore, Rabban covered the constitutional validity of university-implemented “speech codes,” student and professorial expressions of political affiliations, and the extent to which the university as an institution may control when First Amendment rights apply to its students.

In an interview with The Argus, Rabban explained why he chose this particular subject for a Constitution Day lecture.

“I thought that Wesleyan students would have interest in free speech topics,” Rabban said. “I wanted to recognize how many important cases dealing with First Amendment issues have arisen in American universities. The university has been an important place for Constitutional debate and litigation. I also thought that the notion of First Amendment freedom as differentiated from the First Amendment in general might be an interesting topic for the audience to think about.”

Rabban began his talk with a staggering list of cases in which the First Amendment rights of a student, professor, or university were the subjects of major legal contention. In this historical dialogue, he alluded to specific legal cases, including state legislatures compelling universities to include discussions of creation science in classroom settings, whether or not universities can refuse to reappoint a professor fired on the grounds that he was a communist, and a university’s right to fire a professor on the grounds of specific works that ze published.

Rabban emphasized that the First Amendment to the Constitution applies only to state action.

“I think that many Americans believe that the First Amendment protects citizens against private action as well as state action,” Rabban said. “But this common belief is incorrect. Private violations on speech do not violate constitutional rights. Translated into the university context, private universities, including their faculty and students, as well as public universities, are protected against the government. Wesleyan, as well as the University of Connecticut, can obtain relief from legislation that violates the First Amendment.”

Rabban explained that when university trustees or administrators take action against faculty or students, the First Amendment applies only at state universities. Therefore, Rabban pointed out that faculty and students at the University cannot make First Amendment claims against the University and the Board of Trustees. Rabban further acknowledged that this formal constitutional distinction does not always apply in practice because private universities can voluntarily accept the limitations that the First Amendment imposes on public universities.

“Judges themselves have frequently acknowledged that decisions surrounding First Amendment rights at universities have not effectively addressed the meaning of First Amendment academic freedom, or differentiated it well from general First Amendment rights and free speech,” Rabban said.

Following this comment, Rabban proposed that a distinctive First Amendment right of academic freedom should apply only to professional and educational speech. He cited as grounds for this argument the 1950 Declaration of Principles by the American Association of University Professors, which, in his opinion, remains the most influential discussion of academic freedom in the United States.

Hadley noted that she was pleased with the turnout to the lecture and following Q&A session.

“Our hope is to open up a dialogue on constitutional issues, and in this case, academic freedom is very pertinent to things that have been going on not just at Wesleyan but in the larger world,” Hadley said. “So we like to have that mix of people in the audience, and help raise Wesleyan’s profile in the community as well.”

Aobo Dong ’15 added that the lecture inspired him to expand Rabban’s discussion of the First Amendment to the recent controversy regarding former University Librarian Pat Tully’s dismissal from the University.

“The legal protection of administrators and professors is very interesting because it made me think about how the professor can become an administrator and take on other protections with his or her speech or rights,” Dong said. “It’s very interesting to discover this from a legal perspective. I wonder if the point of contention was about legal issues at all, or whether they have the right to fire someone who expressed an educational comment or had held some different working style or different personality.”

Christian Hosam ’15 expressed further interest in the topic, stating that he would have enjoyed a discussion of on-campus issues in the Q&A session.

“I wish someone would have asked about chalking, because there’s an interesting aspect of student academic freedom not being protected,” Hosam said. “Students do not have a specific distinction in academic freedom. I was also interested in his comments on the Steven Salaita case. I think it’s a fascinating and complex case, looking at what academic freedom is going to look like versus what it looks like now. As someone who is following it closely, I hoped he would have been given insight into how it would have been handled.”

YES, I was there, and David gave an inspiring lecture.