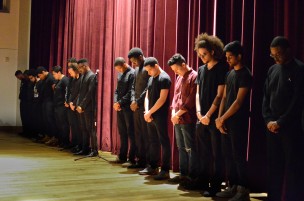

Students, faculty, and prefrosh alike filled Beckham Hall to capacity on April 16 for the annual Invisible Men (IM) Showcase: two hours of powerful performances, films, and speeches from the University’s men-of-color student group. A staple of WesFest programming, the Invisible Men Showcase has grown in scale and production value over the past four years, as IM has evolved from a group mainly centered around the showcase to a broader support group and networking platform for students who identify as men of color.

Jalen Alexander ’14, one of IM’s current chairs along with Rilwan Babajide ’16 and Nkosi Archibald ’16, said the group has evolved dramatically during his time here.

“For my first two years here…what the group focused on was the show,” Alexander said. “What we found was that a lot of [prospective] students would come see the Invisible Men show, say, ‘Oh, there’s so many men of color, they’re active, they’re involved, they’re vocal, they’re expressive,’ but then they would come in the fall and they wouldn’t see our faces…. In my time here, we’ve gone from a group of five or six students focused on organizing the show to a group of 30 consistent students…and now we’re visible year-round.”

Recently created IM programs include the formal event Get Fresh, Men of Color Talks that bring faculty and staff members to talk with students, and a Master Class series that invites successful alumni who identify as men of color to discuss their career paths and provide networking opportunities to current students.

The depth and variety of this year’s showcase programming offered evidence of this broader organizational growth. This year’s IM board members chose “Sankofa,” a Ghanaian term that translates to “reach back and get it,” as the showcase’s theme. Previous years’ themes have included “Insecurities,” “Progression,” and “Momentum;” “Sankofa” was selected to represent the act of reaching into a collective past and applying its lessons to the future.

“Especially with all of the increased waves of student activism happening on campus, we wanted to reach back into the Wesleyan past, because we have a very rich political past,” said Shane Bernard ’14, a member of IM and a performer in this year’s showcase. “We want to show the underclassmen what the students can achieve once they get together in unity.”

A unity of purpose and effort was certainly on display at the showcase, which featured spoken-word poems by Rhys Langston ’16 and Hazem Fahmy ’17, musical performances by Abhimanyu Janamanchi ’17 and Donovan Brady ’16, and a scintillating dance performance by the group Suya 2.0, along with film presentations and reflections throughout. Aaron Veerasuntharam ’14, a member of Invisible Men in attendance, said the show was a success on all fronts.

“I found the whole show really moving and well executed given that there were so many moving parts,” Veerasuntharam said. “I was actually moved to tears during one of the reflections, as were many of the people around me.”

Perhaps the most collaborative effort of this year’s showcase was a film based on the Fisk Takeover of 1969, a hugely important event in Wesleyan activist history. Facing what they felt was institutionalized marginalization and discrimination, members of Wesleyan’s first admitted class of African American students took over Fisk Hall and presented to the administration a set of demands. Successful demands that were met included the creation of Malcolm X House and the Center for African American Studies; The takeover shaped Wesleyan’s identity as a progressive, activist school, and is the University’s strongest connection to the triumphs of the Civil Rights Movement.

The film combined archival footage of civil rights leaders with staged reenactments of the event itself. Directed by Noah Korman ’15 and produced by Bernard and Armani White ’15, the film was an “institutional Sankofa,” as described by Maurice Hill ’14. Korman reflected on the inception of the film’s concept.

“We were just listing things that we could be doing. ‘What if we made a movie about this, what if we made a movie about this? What if we made a movie about the Fisk takeover?’” Korman said. “Everyone in the room was like, ‘Are you really being real about this?’ Because we had just been yelling things at that point. ‘Are you doing this?’ ‘We’re doing this.’ It was a light bulb moment.”

Shot and edited in a time frame of three weeks, the film involved the participation of dozens of members of Wesleyan’s student of color community, as well as the support of faculty members. Because of the subject matter, Bernard said the research process leading up to the film’s production was particularly intense and in-depth.

“When we first started telling the professors that we wanted to do it, they were kind of wary about historical reenactments,” Bernard said. “That only propelled us to work harder. We came back early during spring break and spent time in the archives in Olin digging up information about it. We did phone interviews with members of the vanguard class to get more details about who was where, who played what part in the takeover.”

The filmmakers emphasized the astonishingly quick turnaround from concern around the project’s ambitious production schedule to widespread communal support.

“People aren’t gonna just follow behind something blindly,” White said. “Once they saw the glass of clear water, they took a sip.”

Another high-profile aspect of the showcase was the cypher collaboration with the Rap Assembly at Wesleyan (RAW), which featured live performances from Izzy Coleman ’15, Derrick Holman ’16, and Patrick Stout ’17, as well as a longer rap video modeled off the annual BET Hip Hop Awards Cypher. Additionally, RAW invited Elvee, a local rapper from Middletown, to perform a song with his hype man.

“Elvee was definitely straight hip-hop,” Coleman said. “I feel like a lot of people had strong reactions, whether it was one way or another, but primarily because they had never seen something like that before at Wesleyan, in Beckham of all places. But yeah, it was dope, it was real. It was refreshing.”

The standout event of the night was the final set of Sankofa reflections by Alexander, Bernard, and Hill. Sprinkled throughout the night’s programs were speeches by IM members that touched on the theme of Sankofa and what it personally meant to them. The final speeches were particularly moving to audience members, as they addressed the challenges of living outside of normative gender and sexuality binaries as a student of color at Wesleyan.

“We want to actively create a space where the people in our community could feel safe sharing their experiences, and we wanted to highlight the diversity within our group,” Bernard said. “We’re not a monolithic group; we come from various backgrounds and identities, and the more people who affirm those identities amongst the collective, the stronger we become. Maybe someone else has the same conflicts I had, and by affirming my identity, I’ll help other people feel more courageous to affirm their identities, too. We’re trying to actively become a space that’s not just accepting of all racial identities, but all gender and sexual orientation identities, too.”

Hill said that the overwhelmingly positive response to the speeches was completely unexpected.

“We decided to do our performance about a week before the show. It was pretty spur-of-the-moment,” Hill said. “It was not only for someone else, but it was for us, our stories that we really wanted to express…. We’ve gotten a lot of ‘thank yous.’ Whenever someone tells me that the show was amazing, I don’t know what to say besides, ‘Thank you.’ It was just honesty, it was sharing a part of ourselves.”

Coleman mentioned that the final speeches reflected a large part of what IM is striving to build toward as it continues to expand its programming and support opportunities.

“Last year we wrote a constitution,” Coleman said. “We revisited our goals. We wanted to expand to include more “masculinities,” as it were…. Even if you have a male body, there’s a certain way to ‘be male’ that’s privileged; if you don’t leverage your maleness in a certain way, it becomes an issue. We want to explore that, destabilize that, and just open it up. There’s so many ways to inhabit this body as a man of color.”

-

MaggieCaroline