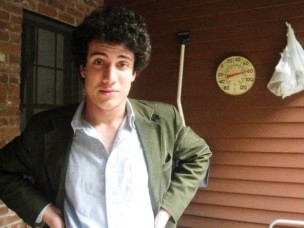

Josh Krugman ’14 and I met on a breezy spring day on the steps of Olin. Barefoot and dressed in blue overalls and two jackets, with a beard and beret to boot, Krugman seemed to be lightly dusted all over with a layer of soil. All of this has the effect of making him look like a root vegetable farmer with a beatnik bent. Indeed, Krugman is a farmer, a poet, and an activist. I sat down with The Argus’s newest WesCeleb to talk about his work in all of these fields (literal and metaphorical), as well as his plans for an upcoming bicycle trip from Vermont to Peru.

The Argus: Why do you think you should be a WesCeleb?

Josh Krugman: I’m not sure that I should be a WesCeleb. But I walk around barefoot a lot, so that might be something that catches people’s eyes.

A: Why do you walk around barefoot so often?

JK: I walk around barefoot because I like the feeling of the ground under my feet. When you wear shoes, every step is the same or very similar. When you walk barefoot there’s all kinds of variety to the textures and temperatures and colors of what’s under your feet.

A: What are some circumstances in which you would not walk barefoot?

JK: When you’re in Usdan.

A: They don’t let you?

JK: They don’t let you.

A: So, what kind of things are you involved with around campus?

JK: I’ve been involved with [Long Lane] Farm for three or so years. And that’s something that has made life meaningful here. The physical work and also the community around the farm.

A: So why is farming important for you?

JK: Farming is work that I love. It gives me happiness to be out in the field interacting with the plants and the whole ecosystem that the farm is a part of. It also makes me happy to be able to give good food to people… I’m also a poet, and you can work a long time on a poem and there are probably relatively few people in the world at large that will be able to relate to it, and that’s sort of a given. But with a carrot or a tomato or something like that, if you make a good carrot, you make friends pretty easily.

A: Are you involved in more things on campus besides the farm? Or off campus?

JK: I’ve been involved with activist stuff a lot here. The farm is definitely an activist project. It’s pro-democracy. We structure ourselves non-hierarchically, we are very inclusive to the Wesleyan community and other communities, and we try to give people the tools to grow their own food. It’s part of the Fair Food movement and the Food Justice movement. I’ve also been involved with divestment campaigns, and [I’ve been involved with] labor stuff here.

A: Are you working on a thesis?

JK: I’m not working on a thesis. I’m a fellow at the think tank at the College of the Environment, where I’m working on an essay about nonhierarchical structures. So I’m working with other students and scholars to create collaborative work around the issue of the commons. My specific contribution is based on my work at Long Lane Farm and on my work with Food Not Bombs.

A: You seem like you have a lot of investment in improving the local community and the Wesleyan community in particular. What are your hopes for future Wesleyan?

JK: My hope for a future Wesleyan would be that it’s able to help people learn without exploiting other people. And I mean people in the broadest sense, including non-human people. Because I think a lot of what happens here happens on the backs of workers and on the backs of communities that engage in insufficiently remunerated production to create the kind of excess wealth that allows for this sort of plush social and material environment. And I don’t think that’s right. And I don’t think that good learning necessarily depends on that kind of excess. So I don’t know what Wesleyan physically looks like, but I hope that it would probably look pretty different.

But I hope that the kinds of movements that are gathering momentum on campus and off campus now will be movements for local autonomy and sovereignty. And the movements for local autonomy and sovereignty in food, which is what I have experience with, can sort of create that kind of transformation in terms of educational autonomy and educational sovereignty. [I hope that] people can get the education they need without having to exploit others.

A: Do you have any post-graduation plans yet?

JK: Yeah. I’m going to work at the Bread and Puppet Circus Theater Company in Vermont this summer. And then I’m going to get on a bike with a few friends and go down to Peru.

A: What do you mean, “get on a bike and go down to Peru”? Like, ride your bike from Vermont to Peru?

JK: Yeah.

A: Tell me more about that.

JK: Well, I spent a year in Peru before I came here, but I did it kind of the “dirty capitalist” way of getting on a plane. And it was wonderful and I made a lot of friends there. And I wasn’t a very dirty capitalist while I was there, but the to-and-from was embarrassing. So, I always wanted to go back, but I also wanted to go back slower and see what was in between and not just do that absurd hopscotch. So my idea is to bike and go from farm to farm and town to town and not give myself a date to get back and work my way down. So by contributing, helping work on people’s farms, I’ll get a little food and sort of make it that way. And the people who are also interested in going are Will Wiebe, who’s a senior, and Meggie McGuire, who graduated a couple of years ago, and Sam King, who’s a UMass student.

A: Is there a question that you wish that I’d asked? Or that you hope people ask about you?

JK: Something that I’ve neglected to mention is animal rights stuff. Something that I would like to see Wesleyan do is to think long and hard as a whole community about whether we’re really comfortable about what we do with the animals in the laboratories here. Because I don’t think people really know what happens in the labs.

A: Can you tell me a little bit about what you know of what happens?

JK: For example, birds having their vocal cords removed in order for somebody to study how they raise their young without the ability to speak seems to me to be particularly cruel… I think it’s easy for us to say, “Well, some animals will just have to be sacrificed for science so that humans can be healthier. We have to solve human disease issues and anything that will help us to do that is justified.”

But when you look at the specific cases, the specific finch that has its vocal cords removed and has to continue living its life and has to continue trying to teach its young what to do and how to speak without being able to speak, it becomes much more difficult to justify on the level of the specifics. In terms of an intellectual methodology, that’s something that I’m interested in. And I think that’s powerful for a broad range of discussions. It has ethical implications in terms of doing justice to specific subjects, and it also has political implications when we think about generalization as sort of akin to vertical hierarchy in terms of political forms. We have this idea of nested levels of bureaucracy or administration overseeing ever more general spheres of life. And we make sort of parallel intellectual moves; we assume that all the diverse facts of the world should be able to be unified into ever more general systems. But I think there’s political power at the base, and there’s also some really good intellectual and ethical power there as well.

A: What was your background before Wesleyan? Did it influence your activism and ideas here?

JK: I grew up in the Pioneer Valley of Massachusetts, and I went to a Waldorf School, where education happens through the arts. And there’s not a distinction made between fine arts and practical arts. So we learned to sew and knit and crochet and care for animals and plants and do woodworking. We also learned sculpture and painting and dance and music and stuff like that. And all that was tied into the so-called academic part of the curriculum in terms of history and math and botany and whatever. We were always painting the plants that we studied in botany and dancing the chemical reactions we learned in chemistry.

And then I went to Deerfield Academy, which is an old New England prep school. That was an excellent place to learn to think and write, and it was very challenging academically. And I was challenged by the political and ethical outlooks of the students which were very alien to me. The sort of affluent, conservative section of the population was something I didn’t even know existed before. But having to explain what I thought to people with whom I had very little in common was very healthy and helped me form who I am and what I think.

I was one of the few Jews and it made me have to be the Jew in every situation where a Jew was relevant. So I had to figure out what a Jewish identity was. And I knew I was on the left but didn’t really know where that was. So I formed an identity, and it turned out to be different than the one I have now, I was more of a Marxist, because I was like, oh, that’s a leftist thing, I’m going to be a Marxist.

And Marx is great, but I ended up being able to appreciate Marxist analysis without being a Marxist later. And if you can’t tell, my thinking now is more influenced by anarchism as far as more practical approach to social and political problems goes.

Leave a Reply