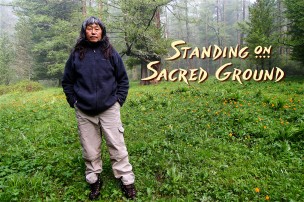

In the early 1980s, Christopher McLeod was a 25-year-old man with a history degree from Yale and an inkling that he wanted to make films. On March 1 and 2, he will arrive on campus to present “Standing on Sacred Ground,” a series of four documentaries that follows eight indigenous communities from Russia to California (“Pilgrims and Tourists”), Papua New Guinea to Canada (“Profit and Loss”), Ethiopia to Peru (“Fire and Ice”), and Australia to Hawaii (“Islands of Sanctuary”).

In the early 1980s, Christopher McLeod was a 25-year-old man with a history degree from Yale and an inkling that he wanted to make films. On March 1 and 2, he will arrive on campus to present “Standing on Sacred Ground,” a series of four documentaries that follows eight indigenous communities from Russia to California (“Pilgrims and Tourists”), Papua New Guinea to Canada (“Profit and Loss”), Ethiopia to Peru (“Fire and Ice”), and Australia to Hawaii (“Islands of Sanctuary”).

A discussion panel and question and answer session will follow each screening. Experts such as Donna Augustine, a Traditional Knowledge Keeper of the Mi’kmaq tribe; Angelo Baca, a Hopi/Navajo filmmaker; and Nikolai Tsyrempilov, a visiting scholar from the Institute of Mongolian, Buddhist, and Tibetan Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences will join Christopher McLeod for an in-depth discussion.

Assistant Professor of Religion, Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies Justine Quijada organized the series and believes these panels will enrich McLeod’s films by providing additional perspectives.

“Between these visitors, faculty and students, I am expecting a lively conversation, and I hope that everyone will join us,” Quijada said.

McLeod’s work has taken him all over the world, but his interest in indigenous communities started with those of the American Southwest, when he was a journalism graduate student at UC Berkeley. Upon learning about the Hopi and the Navajo’s concerns about coal strip mining and uranium mining, McLeod was compelled to do more than observe.

“I went out and made a film,” McLeod said. “I watched machines dig up coal and learned how uranium mines had caused birth defects and lung cancer. Amidst the physical pollution, I kept hearing from everyone—young, old, the elders—that [the communities] had this different kind of relationship with the land that they’d lived on for thousands of years.”

McLeod was struck by that worldview and compelled by the native people’s experience of place, which is tied up in spirituality and which they feel is threatened by corporate capitalism.

“The American Indian leaders were realizing that public education was crucial to their survival,” McLeod said. “They had a sense of wanting to warn this violent, destructive, insane materialistic culture that we’re going of a cliff.”

McLeod believes film to be an effective way of issuing that warning, as well as exposing audiences to the communities he interacts with firsthand, because it evokes a range of textured experience.

“There’s lots of films where a white male anthropologist will lead you through and explain everything—a Western formula that’s dying now, happily,” McLeod said. “The other option is to let the people speak for themselves.”

Letting people speak for themselves is precisely what McLeod has done, and he has found that doing so is powerful enough to bridge cultural gaps.

“We go into a community, and we become part of the scene,” McLeod said. “We get to know people, have fun with them, ask them to do what they do; we try to become invisible. It’s magic, but it works.”

Because partnering with indigenous communities to tell stories is McLeod’s lifework, traveling is a family affair. Miles McLeod ’17, the filmmaker’s son, has accompanied his father to filming in places such as Peru and Russia—and, most prominently, Northern California, where the younger McLeod has been enveloped in Wintu culture since a young age. He has also witnessed the harrowing devastation inflicted upon indigenous lands near and far.

“With the Wintu, it’s the land that’s very barren,” Miles said. “In Russia it’s devastation of a different type. It’s more spiritual degradation. You see a prayer ribbon tied to a tree, and then you see that people have tied their socks or candy wrappers to it. You see massive hanging trees with trash of people thinking they were making offerings. We went with a shaman and a chief from North America, and they had to leave because it was too heavy for them to see their culture disrespected like that.”

Firsthand experience, especially of the Wintu ceremonies, has strongly resonated with Miles.

“Going to a place and meeting these people makes them become part of my fight,” he said. “I’m connected to them.”

Miles McLeod is undecided about what shape his advocacy, or his academic studies, will take, but he’s certain that it will involve the indigenous people to whom his father has devoted his career.

“Words detract from the experience [of traveling],” he said. “Siberia was a cosmic conglomeration of culture. For me, I’ve always seen traveling as a way to learn about the world, not gain something for myself—even though I do gain knowledge. Being [Christopher McLeod’s] son, I’ve had the chance to meet all these different kinds of activists. It gives me something to aspire to.”

Quijada agrees that McLeod’s films provide boundless opportunities for exploration and education, both academic and political.

“The Wesleyan community has a deep interest in both human rights and environmental ethics, so it made perfect sense to screen these films here,” Quijada said. “The struggles of indigenous communities to protect their sacred sites are compelling stories in and of themselves, but they are also extremely thought-provoking. From a theoretical perspective, sacred sites offer an excellent example from which to examine the problems and gaps in current ideas about human rights, as well as providing a way to rethink how we relate to the environment.”

Christopher McLeod agrees that conversation is key to experiencing the films.

“The concept of sacred places can be very foreign and very unfamiliar,” he said. “It’s not something that we have a real language to discuss. Audiences are really moved by the films, by both the beauty and sense of spiritual connection to nature that everybody craves, and also real feelings of disgust and shame over how violent our culture can be.”

On the heels of conversation is political activism, which McLeod anticipates will manifest in different ways for audience members—and even for himself.

“Every story has ongoing current, political policy angles,” he said. “It’s a big planet, and these stories are out there, but they’re not really in our backyards. I’ve been struggling with what I can do to help turn around the destruction and create a sustainable world.”

McLeod finds the indigenous communities he has filmed to be the best guides to sustainability, as these communities have lived for thousands of years on the land whose destruction now seems imminent.

“Part of the vision for the future needs to include the concept of the sacredness and the aliveness of the natural world,” McLeod said. “Many people don’t have that experience because we’ve denied it, and gone down a different path where the earth is a dead machine. The indigenous people are trying to tell us that it’s alive.”

Comments are closed