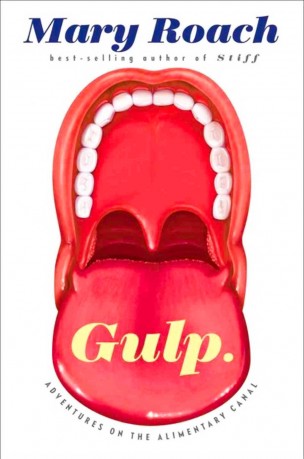

Had it been written by anybody else, “Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal” might have been an awfully disgusting account. Luckily for the reader, though, “Gulp” was written by Mary Roach ’81, who has no qualms about getting down and dirty—and Roach’s step-by-step chronicling of the digestive tract does, indeed, get dirty.

In the book, which is told in 17 sections, Roach works her way down the alimentary canal in a journey that includes sampling dog food in St. Louis, Mo.; consulting experts about oral processing and saliva in the Netherlands; chatting with rectal smugglers at a California state prison; and contemplating a colon with a 28-inch circumference in Philadelphia.

Roach is not, in other words, a passive reporter. “Gulp” is part popular science and part MythBusters. Roach is unflinchingly curious about the inner workings of the human digestive tract, and she is never shy to probe the experts she interviews along the way. She also doesn’t hesitate to look into obscure accounts to address her questions: Why is the least common form of bulimia chewing food and spitting it out? Why doesn’t the stomach digest itself? Is it possible to “reverse eat” (that is, suck up food from the rectum, absorb the nutrients, and vomit up feces)? Did Elvis die from constipation?

Roach’s experts add flavor to the tale. The first professional we meet is Sue Langstaff, a bona fide wine- and oil-sniffer with a nose as sensitive as a dog’s, who guides Roach through an afternoon of oil tasting (during which Roach hilariously struggles to identify the many variations of oils before her). “Nose Job,” the first section of the book, addresses the role of smell in tasting food, and Roach raises fascinating observations about the difficulty of finding names for smells. Langstaff, meanwhile, describes scents as though they are paintings, thanks to her mega-nose and the Harley Davidson she rides to catch more whiffs of the air.

Humor is indeed an essential ingredient in every part of the journey from the nose to the rectum, and Roach applies it liberally. Even her footnotes avoid being dull. The note that corresponds to the word “uvula,” appearing when Roach visits an oral processing lab, states, “Its full medical name, and my pen name should I ever branch out and write romance novels, is palatine uvula.”

Another funny footnote corresponds to Roach’s description of a feud between Horace Fletcher (the nineteenth-century proponent of the extreme chewing, or “Fletcherizing,” of food so that it is not swallowed as a solid but slides down the throat by default) and John Harvey Kellogg (the nutrition expert of the same era who valued whole grains and brought notoriety to granola). Here, Roach’s footnote points to the men’s rivalry over preferred excretion.

“The two parted ways over feces,” Roach informs us. “Kellogg’s healthful ideal was four loose logs a day; Fletcher’s was a few dry balls once a week. It got personal. ‘His tongue was heavily coated and his breath was highly malodorous,’ sniped Kellogg.”

Her asides are likewise hilarious. When Roach journeys to a California prison notorious for its “hoopers” (prisoners who smuggle in drugs, razor blades, and the occasional iPhone in their rectums) for an interview with an inmate, she first briefly consults a contraband interdiction officer who shows her a collection of bags and boxes containing hooped (rectally smuggled) items. One prisoner, she learns, was caught with two boxes of staples, a pencil sharpener, sharpener blades, and three jumbo binder rings stored in his rectum.

“He became known as ‘OD,’ for ‘Office Depot,’” Roach reports.

In California prison, there’s also the harrowing moment in which Roach discovers the nature of her prisoner interviewee’s crime just moments before meeting with him: he is a murderer.

“I glance down at my list of questions, which includes ‘Might hooping be a form of what the Journal of Homosexuality calls ‘masked anal manipulation’?’” Roach writes, and her readers’ hearts begin to pound alongside hers.

As with most of Roach’s interview subjects, though, her prisoner turns out to be a lovely gentleman who is remorseful of a murder he committed decades ago. He’s also surprisingly adept at explaining the physics of rectal smuggling, a feat that has even Roach wincing.

Much of the charm of “Gulp” is its author’s eternal curiosity and her fearlessness in the pursuit of knowledge. She will truly ask anything, and for that she is often rewarded with peace of mind. For example, when flatulence-expert gastroenterologists Michael Levitt and Julie Furne inform her that hydrogen sulfide, found in gas, is fatal in confined spaces, Roach is up-front about her concern.

“When it’s cold, I tell Furne, I sometimes sleep with my head under the covers,” Roach writes. “Winter is brussels-sprout season, and they’re Ed’s [Roach’s husband’s] favorite side dish.”

Furne assures Roach that the air inside her comforter makes her flatulent husband’s emissions harmless. Roach is relieved, though we aren’t sure what Ed’s opinion about the matter is.

With Roach as our expert rower, our gondola ride along the alimentary canal is scenic but rarely graphic, and it’s always entertaining—she proves to be a cheery, personable tour guide. And the (figurative) cherry on top: perhaps her curiosity about bolus formation was cultivated in a Wesleyan dining hall.

Leave a Reply