Walking around the University’s campus, students rarely see a cohesive group of buildings. They instead see a hodgepodge of materials and designs, an accumulation of houses, halls, and dormitories that, since Wesleyan’s founding in 1831, have slowly been added to the University’s campus.

Walking around the University’s campus, students rarely see a cohesive group of buildings. They instead see a hodgepodge of materials and designs, an accumulation of houses, halls, and dormitories that, since Wesleyan’s founding in 1831, have slowly been added to the University’s campus.

The Center for the Arts looks nothing like Exley Science Center, despite having both been completed in the 1970s. Both of these appear alien after passing through College Row. Contrasted with almost any other building on campus, a single structure seems randomly plopped down from another time and place. And, to an extent, it was: each building is a product of the time during which and the architect by whom it was constructed.

Nevertheless, within the school’s architecture, order does exist. A closer look into the origins, designs, and organization of certain buildings on campus reveals more than a decade of growth fueled by the creative contributions of a single man: Henry Bacon.

Bacon was an architect for the New York City firm of McKim, Mead, and White in 1906 when Stephen Henry Olin, a Wesleyan trustee and son of an earlier University president, began looking for someone to design the fraternity house for Phi Nu Theta, more commonly known as Eclectic.

According to Chair of Art and Art History Joseph Siry, Bacon was one of the preeminent neoclassical architects in the United States. With his firm, he helped design the 1893 World’s Fair Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which included a display of neoclassical architecture that influenced the design of public buildings around the country.

Before then, in 1884, he studied architecture for a year at the University of Illinois before moving to Boston to study and work with his older brother, an architect and archaeologist. Bacon won a two-year traveling scholarship in 1889 to go to Europe, where he studied classical architecture sites in Greece and Italy.

Bacon was particularly partial to the Parthenon, so when Olin wanted “an economical building that would nevertheless have a classical aura” for Wesleyan’s campus, Bacon came highly recommended. Although Bacon’s style meshed with the look Wesleyan was already developing, the sheer number of his designs for Wesleyan, including the Skull and Serpent Tomb (1914), Van Vleck Observatory (1914), Clark Hall (1915-1916), Hall Laboratory (1926), and Olin Library (1925-1929), solidified the era as his own.

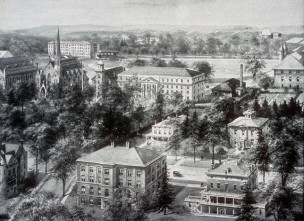

Wesleyan’s architecture had gone through various stylistic phases by the time Bacon arrived. When Wesleyan was founded in 1831, it took over the preexisting structures of North College and South College, which had both been built in 1824. They, along with the rest of the structures along College Row–including the ’92 Theater (1866) and Judd Hall (1869)–were constructed from Portland brownstone, which came readily available from a nearby quarry.

In the early 20th century, brick replaced brownstone as the major building material for American college campuses. But earlier, a Greek revival had also swept through the school, a phase visible in Russell House (1828-1830) and Alsop House (1838), home to the Davison Art Center. Both trends lent themselves to the designing of Eclectic years later.

“If I look along High Street between Russell House and Eclectic, I’m seeing some consistency of vocabulary across town,” Siry said.

That classical vocabulary ties together all of Bacon’s work. According to Siry, Bacon preferred the Greek Doric order, which, as in the Parthenon, features smooth columns with simple square bases. It was seen as more masculine than the spiraling Ionic order or the ornate Corinthian order apparent in Russell House, and as such, it became incorporated into not only Eclectic but also Clark Hall and The Tomb. The house also differentiates itself from the previously constructed fraternity houses of Psi Upsilon (1894) and Chi Psi (1904), now 200 Church, because of its horizontal rather than rounded entrance.

Eclectic in particular holds a special place in architectural history. Over Homecoming/Family Weekend, it received a dedication as a National and State Historic Building from the National Register of Historic Places and the State of Connecticut Historic Registries, mostly because of its significance in the career of Henry Bacon. After finishing Eclectic, Bacon won the national contest to design the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., in 1911. Bacon used much of the same classical vocabulary in his visions of both buildings.

“Of all the things he did before the Lincoln Memorial, [Eclectic] was one of the closest in form,” Siry said. “It’s the preceding essay.”

The elements of Bacon’s designs that appealed to Olin also appealed to the Lincoln Memorial committee.

“I think that was what was so striking to people at that time, that his stylistic voice resonated with people’s expectations for the public function of that memorial,” Siry said.

The strength and restraint implicit in the Doric order, displayed prominently in the many white columns of the memorial, matched up with how Americans perceived the figure of Abraham Lincoln. Bacon’s design, Siry said, was the “national definitive resolution” of the process of cultivating Lincoln’s memory.

At the same time, designing that memorial also became the defining moment in Bacon’s national legacy.

“It was really his contribution to the Lincoln Memorial that gave him his immortality,” Siry said. “Because it’s really about him; it’s about Lincoln, nominally, but it’s really Bacon’s persona as a designer that registers in that building.”

Locally, however, Bacon’s memory persists in his contributions to Wesleyan. In 1914, he worked with Olin to develop a plan for the campus that helped to shape the University for the years to come. Bacon envisioned a collection of buildings around Andrus Field, and although many were never constructed, he did sketch out the group of buildings that would become Clark Hall, Olin Library, and the Public Affairs Center, which at the time was called Harriman Hall.

Bacon died in 1924, before he could see his designs for Olin Library or Hall Laboratory (now Hall-Atwater) carried through. But in the time he spent here, Bacon contributed significantly to the campus experience. His designs, products of his education and the period in which he created them, continue to define the look and feel of Wesleyan University.

Leave a Reply