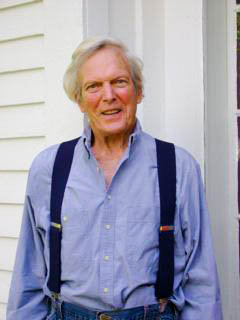

At his memorial service, professors, friends, and family remembered Professor of Letters, Emeritus Franklin Reeve as a man with an excitement for learning, an ability to spur discussion, and a wit faster than a speeding bullet.

“He had this impish and consistent desire to undermine whatever you thought you knew and to force you to think outside the box,” Professor of German and Letters, Emeritus Herbert Arnold said.

Franklin D’Olier Reeve passed away on June 28 at the age of 84 after devoting nearly half of his life to teaching at the University, first as a professor and chair of the Russian Department from 1962 to 1966, and then as a professor in the College of Letters until 2002.

Reeve’s former colleagues, as well as his friends and family, filled the seats at the reception, held at Russell House on Friday, Sept. 20. Several shared their memories of him, and others read aloud Reeve’s own words, including a passage he had written in Russian.

Arnold, who taught a colloquium alongside Reeve, remembers the course as a new and exciting learning experience for both him and the students, especially since the two professors often “fundamentally disagreed” on their interpretations of the material.

“It was a ping pong of ideas going back and forth, and students’ heads [would be] swiveling,” Arnold said. “That was quite deliberate, and Frank was smiling about it.”

At the memorial, Professor of Letters Emeritus Paul Schwaber read aloud a tribute to his former colleague that also appeared on President Michael Roth’s blog.

“I remember Frank Reeve as a tall, extremely handsome man,” Schwaber said. “He smiled ruefully and spoke very rapidly, as if barely able to control his rush of thought or questions.”

Reeve’s notable features and charisma were passed on to his son, actor Christopher Reeve, famous for his role as Superman in the 1978 motion picture. The two so closely resembled one another that Professor of Physics, Emeritus Bill Trousdale recalls mistaking Christopher for his father at a book signing.

“Gee, Franklin, you are looking young!” Trousdale recalled nearly saying to the movie star.

Christopher Reeve may have also inherited his father’s talent for the arts: Franklin Reeve acted professionally shortly after graduating from Princeton and before pursing a master’s degree in Russian at Columbia.

However, Frank ultimately decided to give up acting upon realizing that it would impede his ability to write poetry.

“For the first time I discovered what happens when a person really acts: the self disappears; you entirely, inside and out, become the character,” he once wrote.

Many would agree that this sacrifice was worthwhile: poetry was yet another area in which Franklin Reeve excelled. Reeve wrote 10 volumes of poetry, and he was the recipient of the New England Poetry Club’s Golden Rose Award and various other awards.

Over his lifetime, Reeve wrote a total of six novels, five books of criticism, eight Russian translations, and five plays. Most famously, he acted as an interpreter for Robert Frost on a visit to Soviet leader Nikita S. Khrushchev in 1962, during which Frost served as a cultural ambassador on behalf of the United States.

“Widely learned, he was polylingual, witty, keen with pun and irony,” Schwaber said. “There were few things he seemed not to know.”

That which Reeve did not know, he tried earnestly to learn with great confidence. John Basinger, Professor Emeritus of Theater and Sign Language at Three Rivers Community College and husband of Professor of Film Studies Jeanine Basinger, recalls Reeve’s attempts to study sign language.

“He was willing to just flub it up,” John Basinger said.

Though Reeve may have given off the impression of being “all-knowing,” John Basinger noted that even he was sometimes prone to ad-libbing.

“Anyone who yammers as much as me is going to do a bit of humbuggery,” he said.

Reeve often liked to improvise his lectures and think on his feet, and he relished the opportunity for spur-of-the-moment remarks.

“A certain amount of that was just keeping fingers crossed, but [Reeve] was unafraid of that,” John Basinger said.

It is likely that Reeve’s talent with improvisation and knack for communicating as an actor and poet helped him develop into the skilled lecturer that captivated so many students and faculty.

“I always admired him,” Trousdale said. “He was a combination of forceful and generous. If you kept talking to him about something, you never came away thinking, ‘Oh, that was a stupid idea.’ He wasn’t about putting someone down, but instead tried to engage them.”

In an interview with the New York Quarterly, Reeve once credited poet and critic R. P. Blackmur for developing his passion for poetry after taking the professor’s creative writing class at Princeton.

“My whole life changed when I went to college,” he said.

As his son Brock Reeve suggested during the memorial service, Frank’s time at Wesleyan might have influenced his life just as dramatically as his time at Princeton initially did.

“My father had several chapters of his life, but the theme that runs through these chapters is this place that is Wesleyan,” who is now Executive Director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute. “Wesleyan provided a rich, flexible environment that allowed my father to explore his interests, passions, and abilities in multiple ways.”

It is a huge loss for the Wesleyan community that Franklin Reeve is no longer with us, but he continues to live on through the words he has left behind. One poem in particular, entitled “Home in Wartime” and published in October 2002, may offer some advice for how we should cope with his passing:

If I die first, gather the lost years

with the late September apples. At sunset ghost me

beside you on the steps to watch

the tangerine-lavender clouds turn gray.

Leave a Reply