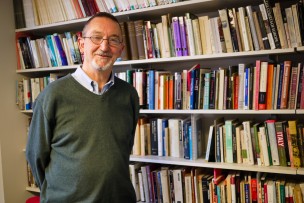

Visiting Professor of History Professor Tony Day is currently teaching a course on Modern Southeast Asia, the syllabus of which includes traditional historical and analytical texts, a range of documentaries, films, poetry, and historical fiction. He sat down with The Argus in his office (which he shares with Professor Laurie Nussdorfer in the Public Affairs Center) to discuss books, the merits of being a visiting professor, and his experiences in Southeast Asia.

The Argus: What are you currently reading?

Tony Day: At the moment, I’m reading “The Book of Salt,” by Monique Truong, a novel about a Vietnamese cook who works for Gertrude Stein in Paris; “Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War,” a book about jazz artists during the Cold War; and “River of Smoke” by Amitav Ghosh, his second novel about the opium trade in Southeast Asia and China.

“The Book of Salt” sits in my car and I’m reading it one bit at a time while I wait for my 13-year-old son to get out of school or finish his umpteenth soccer practice of the week. I’m very interested in Vietnam (I’ve compared Indonesian and Vietnamese literature in a couple of publications) and have been learning Vietnamese for several years.

“Satchmo Blows Up the World,” by Penny von Eschen, is a wonderful study of how black jazz musicians sold “America” to the world during the Cold War at a time when African Americans were fighting for their own basic rights at home. I’m working on a book that compares writers, painters, filmmakers, and musicians in Asia, Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the U.S. during the Cold War.

I’m reading Ghosh’s book because it’s a wonderful historical novel (I always have students read novels when I teach them history), but mainly because I’m mentoring a student in CSS who is writing a senior essay on the Opium War, which is treated in the novel. My student is trying to “displace” the Opium War from its hallowed location in British imperial and Chinese national history. Ghosh’s take on the war is entirely from an Indian perspective.

A: So do you always read three books at once?

TD: I have a lot of interests, so that happens quite often. You have to understand what reading means to an academic like myself. I dip into books, put them down, cogitate on a page here, a chapter there. A year later I might read the whole book and find entirely new things to think and say about it.

A: How many books would you say that you read in a year? Or in a semester?

TD: When I teach a course, I like to learn more about the subject, catch up with the latest work, etc. If I’m teaching a subject I’ve never taught before, like Modern China, which I taught for the first time four years ago at Wesleyan, the sky’s the limit. So, to answer your question, 20-30 new books a semester is not unusual for me, plus renewed acquaintances with old friends.

A: You’re currently housed in Professor Laurie Nussdorfer’s office, so this isn’t really your bookshelf, but what’s your bookshelf at home like?

TD: Well, my wife, son, and I live in a very small apartment in Calhoun College, one of the residential colleges at Yale. It’s a nice apartment, but we don’t have a lot of space for books, so what I have set up in the living room at the moment is a working bookshelf on Southeast Asia, which is what I’m teaching at Wesleyan this semester. In the bedroom we keep a bookshelf of general literature; it starts with the poems of John Ashbury and ends with novels by Emile Zola. The rest of my books live in a storage room in the basement of Calhoun. From left to right, there are bookcases with books on Southeast Asian history, Chinese history, Indonesian history, Asian literature, Asian film and theater, Dutch and Dutch colonial East Indies literature (with a shelf devoted to Sir Walter Scott, a major influence on Dutch literature in the 19th century), imperialism and the cold war, postcolonial and postmodern theory, Indonesian literature, and world literature. These are the subjects and disciplinary areas that I draw on for my own work. My wife often goes to the Calhoun gym, but I keep in shape carrying books up and down four flights of stairs to and from our apartment, depending on what I’m teaching or writing on at the moment.

A: What’s it like to be a visiting professor, and to be one at Wesleyan for five years?

TD: It’s absolutely delightful; it’s a perfect life for me. It really allows me to do what I really enjoy doing, which is teaching, and it is also a great way to balance my personal and academic life, especially since my wife is a full-time professor at Yale. I get to teach, but also take care of my son.

A: Although you’ve mainly taught courses on China at Wesleyan, from what I understand your area of academic focus is Southeast Asia and, more specifically, Indonesia. How did you develop this interest?

TD: I went to college during the 1960s, but until my junior year I was pretty oblivious to what was going on in the world. I majored in English History and Literature in Harvard and wrote my senior thesis on Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” and Thomas Kyd’s “The Spanish Tragedy.” It was the American War in Vietnam that motivated me to start learning about Southeast Asia. When I graduated from college, I joined the Peace Corps and taught English and elementary school teaching methods in a teacher-training college on the island of Mindoro in the Philippines. In those days, Mindoro was an isolated place, best known for its mountain people, the Mangyans (about whom the Yale anthropologist Harold Conklin has written many wonderful studies). After two years studying Tagalog and learning about what Filipinos thought about America (a complicated subject!), I applied to several graduate programs, and was accepted to the history department at Cornell, which has a very strong program in Southeast Asian studies. Since I had spent two years in the Philippines, I decided to study another part of Southeast Asia—Indonesia. I finished my Ph.D. in 1981. By that time, I was also teaching courses on Southeast Asia as well as Asian and cross-cultural theater and performance at the University of Sydney, Australia.

A: You must have traveled a lot in Southeast Asia. What would you say is your favorite thing about the region, outside of academic interests?

TD: I love to travel in Asia. Talking to people on the road is always wonderful, particularly if you speak a local language (I know Indonesian and Javanese; I’m currently reviving my Tagolog and learning Vietnamese. Next on my list: Thai). I love living in the tropics. A lot has changed since I went to Southeast Asia forty years ago. I’m not all that wild about traffic jams in Jakarta and Bangkok. In the old days, you’d get on a bus in the Bontoc province of the Philippines or in Surakarta, Central Java, and literally fly through the night, not entirely certain how long the trip would take or whether you’d ever arrive in one piece. In the meantime there were people to talk to, clove cigarettes to share, and lots of pigs and chickens to commiserate with.

A: So what would you say is your favorite cuisine?

TD: I would have to say Javanese food. The best meal I’ve ever had—and I’ve had many, many good meals in Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia—was actually at a bus station at the eastern tip of Java, while we were waiting to go to Bali. We sat, tired and sweaty after one of those “flights” through the night from Central Java, at a small roadside food stall, enveloped in fumes from assorted snorting buses. It was a menu prix fixe: bee’s larvae (nasi tawon), served with rice, steamed in a banana leaf, seasoned with white pepper, washed down with hot tea. That was the best meal I’ve ever eaten in my life. (The next best was at a Thai restaurant in Camden Town, London, with my host, a Reader in Thai film studies at the University of London, doing the ordering.)

A: In your course on Modern Southeast Asia, you mentioned that one of the main textbooks on the syllabus, “The Emergence of Modern Southeast Asia,” once had the title “In Search of Modern Southeast Asia.” What do you think of this idea of the “emergence” of the region? Do you think that Southeast Asia is finally gaining its own distinctive recognition, as opposed to how it’s been traditionally subsumed under the general idea of Asia?

TD: That’s an important question, and yes, I certainly think so. Southeast Asia is really coming into its own—it’s been quite a struggle, considering its tumultuous history (colonialism, the Cold War, natural disasters…), but things are on the move. Over the last several years, I’ve been hugely impressed by the young Southeast Asians I’ve met, both in the region and at universities in the U.S. These are incredibly bright, creative, sophisticated people who speak and write English with amazing skill and who are becoming interested in “Southeast Asia,” not just their own countries or the “West.” Colonialism killed regional awareness in Southeast Asia. But it is coming back to life now, in large part due to the phenomenal rise of China. As Southeast Asian societies become more democratic, they will demonstrate to the world how Asian nation-states can be tolerant, cosmopolitan, multicultural, and masters of their own destinies.

Leave a Reply