c/o onlinemovieshut.com

Walter Haas, Jr. taught the world of baseball a lesson in the 1980s: it is not the size of the market that dictates how a team plays, but the size of the wallet. Pouring money into his Oakland A’s teams with the help of longtime general manager Sandy Alderson, Haas bankrolled great teams rather than built them—the A’s team that brought a World Series title to Oakland in 1989 ranked fifth in the Major League in payroll. But when Haas passed away in 1995, new owners Stephen Schott and Ken Hofmann tightened Alderson’s purse strings, forcing him to seek out creative methods to build a winner on a budget. Thus, the sabermetric revolution was born, with Alderson instituting a total culture change in Oakland. It no longer mattered how much money was spent, but where it was allocated. In 1998, Alderson left the A’s to take a job in the MLB front office. He was replaced by his former Assistant General Manager, Billy Beane.

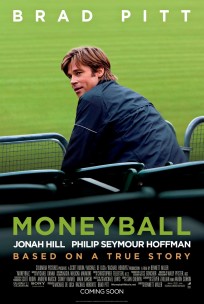

Beane is the focus of the narrative presented in “Moneyball,” the story of a former ballplayer and his pudgy, Yale-educated sidekick Peter Brand, in their efforts to overhaul a flawed system of putting together a baseball team. My issue with the film is that it focuses too heavily on the personal story of the protagonist while sacrificing the emphasis on sabermetrics. When you look through history, Billy Beane is not the sole individual responsible for sabermetrics, nor is Sandy Alderson, nor is Bill James, the father of advanced analytics in baseball. Sabermetrics is a communal advancement towards the ultimate goal of judging the true value of baseball players.

Achievements in the field of sabermetrics have come from various sources, ranging from statistical analysts like Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight fame, to others in baseball, like General Manager of the Tampa Bay Rays Andrew Friedman, who built upon the formula used by Beane in Oakland. While the story is somewhat related to Beane’s personal narrative, putting one man at the center of a statistical movement seems to defeat the point of the movement itself.

Miller, along with screenwriters Aaron Sorkin and Steve Zaillian, was tasked with condensing the detailed story of a full year in a baseball front office into a two-hour film. A book can walk you through the details, taking you through all the complex intricacies of the system. But in two hours, the “Moneyball” crew was forced to cut through equations and get to the results. That is why we get the story of Scott Hatteberg, a slow slap-hitter with a penchant for getting on base, but not Miguel Tejada, Eric Chavez, or Jermaine Dye, the A’s top-three sluggers for the 2002 season. It can easily be argued that these three players accomplished more than a team of Hattebergs ever could have in Beane’s pursuit of run production, but there were two problems that largely kept them out of the film: they were on the team before Beane’s and Brand’s revolution began, and the A’s could never convince them to take pitches and draw walks. Tejada may have played well enough to earn himself the 2002 American League MVP award, but he didn’t play in a way that earned him screen time. The same can be said for Tim Hudson, Barry Zito, and Mark Mulder, Oakland’s trio of young ace pitchers. They too were part of the old guard, and since their job was about preventing runs rather than producing them, they did not fit within the narrative.

So the audience needs Beane to take them through this story of how this group of has-beens and castaways won 103 games. While it might not adhere perfectly to the spirit of the book to cast Beane as a cinematic hero, the audience does follow Beane’s story closely. From the A’s sputtering in last place in their division early in the season, to the historic 20-game win streak that launched the team to the top of the Major League and into the national consciousness, to the loss to the Minnesota Twins in the first round of the playoffs, it is clear how anomalous a Major League Baseball season can be: one game is a terribly small sample size, and every game counts. But when you put those day-to-day deviations together, they trend toward a common truth: Billy Beane built one of the best teams in baseball with the wisdom of hard analytics, and the method does validate the madness. If you take just that much with you when you leave the theater, then Hollywood’s “Moneyball” did teach you some baseball after all.