The Knicks aren’t just any basketball team– they’re the New York Knicks. They play in the “World’s Most Famous Arena” and it’s their duty to represent our city in the world of sport. To be fair, the gladiators probably had their share of tough times in the Colosseum. That’s a given. But did they ever play basketball at Madison Square Garden in front of 19,000 raving New Yorkers? Did the Post ever write a three-page spread on a gladiator’s game-blowing mistake? There’s no other experience like playing basketball for the city of New York. Some rise to the occasion, and some do not. There’s no unconditional love here. Either you perform, or you get the hell off the court and let someone else try. What the fuck do you think this is? Vancouver?

At least that’s the way it used to be. The glory days of Latrell Sprewell, Allan Houston, and of course, Patrick Ewing came to a close a while ago. We’re a sorry bunch now, us Knick fans. We saw our owner James Dolan strangle himself financially with some of the worst, boneheaded management in the history of professional sports. We witnessed the apocalypse of the Isiah Thomas administration. We cringed as Stephon “Anthrax” Marbury infected our locker rooms. We watched in horror as our squad of overpaid, over-the-hill has-beens and nobody draft-picks donned our precious orange and blue and embarrassed us night after night. The worst of it may be behind us, but the struggle is far from over.

I don’t know if I’ve ever been as depressed as the last time I went to the Garden. My uncle Chris, who took me to more sporting events than I could count when I was a little kid, managed to get tickets to a Knicks/Suns game. I wasn’t really sure if I wanted to go, but I figured what the hell, I hadn’t seen him or the Knicks in a while. I met him at 35th and 7th, he gave me my ticket, and we went in.

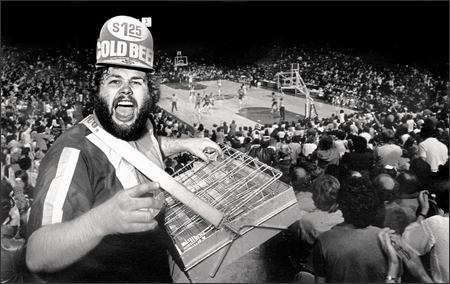

Nothing about the Garden would really lead you to believe it was the World’s Most Famous Arena if it wasn’t written on every sign, wall, and food counter in the building. The hallways are lit with a harsh, fluorescent light that ensures each advertisement lining the white walls is as visible as possible. The floors are a sterile-looking, often sticky, beige linoleum, and the whole place smells like fried food and flat beer. On an average night, people are everywhere. Overweight mothers trying to control their kids, scores of men waiting for the bathroom, each hoping to score a urinal over pissing in the sink, people selling programs, beer vendors. Cries of “Beer’re!” echo in that deep, guttural tone– as if every beer man has swallowed a bag of marbles before the game. My uncle insists on explaining the unique art of a Madison Square Garden beer man. The best of the best, he says, are not only ceaselessly dedicated to their craft, projecting their booming voices over impossible distances until they’ve gone hoarse, but can also give you key insights into the game, like whether or not Charlie Ward is wearing his lucky sneakers or the number of shots Latrell Sprewell made in warm-ups. Sadly, these days, the classic beer vendor has slowly become a dying breed.

Everything about the Garden used to be exciting. Walking along those hallways was like a furious drum roll for that moment when you enter the real arena, that transition from bright florescent lights and food courts to the darkly lit seats and the golden aura of the basketball court. If I ever left to get food or go to the bathroom, it was at a near-run. Nothing was more aggravating than waiting in line for a hot-dog and watching the game on those little food-court televisions. I’d book it back to the seats top-speed so my uncle could give me a quick play-by-play of what I’d missed.

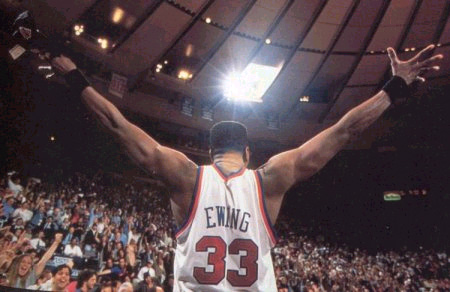

I wish I could still get that worked up about missing a minute of Knicks’ basketball. They’ve betrayed me for too long though. Any sort of mysticism I used to associate with the Garden has been buried by horrible trades, ball hogs, injuries, sex scandals, team discord, and all the other pains that come with six consecutive losing seasons. Ever since I started buying adult tickets at movie theaters, the Knicks have been the laughingstock of the NBA. Any self-respecting Knicks fan can tell you the exact moment the team plunged into oblivion: the Patrick Ewing trade, a trade so blasphemous that the gods continue to punish us for it to this very day. Ewing, our big man, our franchise player, the very heart of our championship-contending team was traded to the Seattle Supersonics in 2000, after fifteen years of service in a Knicks uniform. After that, everything started to collapse.

The year before, though, was one of the greatest in the history of New York basketball. The chemistry of our starting five was undeniable. Ewing at center, Larry Johnson at power forward, Latrell Sprewell at small forward, Allan Houston at shooting guard, and Charlie Ward bringing up the ball at point guard. At the heart of the Knicks’ image and game plan was Ewing. At 38, Ewing definitely wasn’t getting any younger by the 2000 season. His back was creaky, his knees questionable at best, but for a 7-foot man he still made it through the better part of 33 minutes a game that season– impressive for any center his size, especially one as profoundly lanky as Ewing. His offensive output wasn’t showing any real signs of age either. That season more than ever, Ewing perfected the five-to-ten foot, one-handed turn-around shot. Faking one way, twisting the other– it was a rare day when a rival center could contest the Ewing turn-around jumper.

My most enduring memory of Ewing though, was his free-throw form. Nobody took free throws like Patrick Ewing. As a center who predominantly played down low, Ewing naturally got fouled a lot. He took 283 shots from the free-throw line over the course of 63 games that season. Unlike most big men, however, he maintained an extremely respectable free-throw average of 74% throughout his career. That number, if anything, was entirely due to perfection of his routine. First he stepped to line with his right foot slightly ahead of his left and receive the ball from the referee. Then two quick, hard bounces with the right hand. Next, he spun the ball backwards in the air, caught it, and carefully rotated it in his shooting hand until his fingertips rested precisely on the seams. Finally, his knees sprung in two bouncy, successive movements, and he propelled his entire body upward, releasing the ball at the highest possible point with a flick of his giant wrist, almost as if he was reaching his hand into an imaginary cookie jar far above his head. If it was the second of two free-throws and he’d made the first, Ewing did classic Ewing. He held his hand in the cookie jar way up in the air, and either walked or skipped backward down the court, looking both ways just to make sure everyone in the arena was paying attention. In third grade, I mastered this routine to the very last detail. I’ve since subconsciously followed it on every free throw I take as my own sort of meager tribute to one of the greatest to ever play the game.

There was a certain, indisputable class that Ewing brought to Knicks basketball, a certain type of class conspicuously absent from our ’08-’09 squad. Ewing, a native of Kingston, Jamaica, sported a classic 90’s haircut in the high-top fade, wore only the finest Italian suits off the court, and inevitably charmed your pants off with a single smile. I don’t mean to portray him as a saint or anything, but the man was special. So special that he volunteered to donate his kidney to long-time rival and prolific Knick-killer Alonzo Mourning of the Miami Heat. Just to make this clear, Alonzo Mourning was probably one of the two guys– the other undoubtedly being Reggie Miller– that every Knicks fan hated. The Mourning-Ewing match-up was as epic a rivalry as any in history– Athens vs. Sparta, Godzilla vs. King Kong, Biggie vs. Tupac. It was like watching Ali and Frazier on the basketball court. Once either of them got the ball down low it was as if everyone else on the court stopped what they were doing and just stared out of sheer respect.

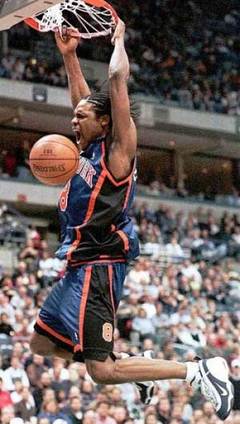

Of course, the ’99-’00 team goes deeper than just Ewing. We had Latrell Sprewell, easily the most frightening man in the league, at small forward. When Sprewell first got to New York, fans everywhere were up in arms. We traded away the scrappy and charismatic John Starks for this corn-rowed menace who not only strangled his previous coach as a Golden State Warrior, but also bore a striking resemblance to a pit-bull. He was better known for his exotic car dealership and his unique taste in hubcaps than for his play. However, Sprewell quickly won over the hearts of Knicks fans everywhere with his intensely aggressive style and his slashing drives to the basket. The only person I knew who didn’t warm up to him was my mom, who never really seemed to get over the fact that he choked his coach. As long as he averaged 19 points a game, the rest of New York and I saw considered it water under the bridge.

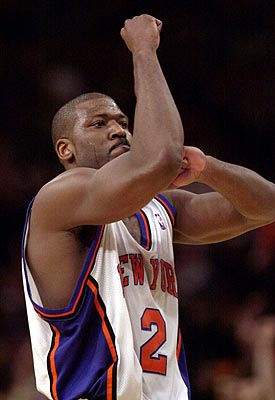

Larry Johnson, our seminal power forward, was known around the league for his superhuman skill for talking trash and his supremely clutch three-point shooting. Johnson lived in the fourth quarter. He even named his dog, a golden retriever-beagle mix, Fourth Quarter. After he made any sort of crucial three pointer, Johnson would walk backwards down the court slowly to make sure the TV cameras could follow him, with his arms going from a “L” (right forearm in a straight vertical position, left fist touching the right elbow, and the rest of the left laying horizontally perpendicular to the right) to a “J” (switch of right and left) formation, almost as if he was adding his own little signature to the shot. When you’re spelling your initials with various limbs, you know you’ve reached the pinnacle of trash talking.

If nothing else, though, I’ll always remember Johnson for his master feat, the instantly legendary Four-Point Play. It was the third game of the semi-finals, the Eastern Conference championship, a best-of-seven game series tied at one game a piece against one of our worst rivals: Reggie Miller and the Indiana Pacers. Due to some poor planning, the Bartle family was stuck in typically horrendous LIE traffic for the entirety of the game, and we’d been forced to listen to it on the radio. The Pacers had held a small lead throughout the tight game, and heading into the fourth quarter the situation looked pretty tense. Even my mom, who usually could not have cared less about professional sports, was anxiously biting her nails. With eleven seconds left in the fourth quarter and the Pacers up by three, the Knicks inbounded the ball. Everyone in the building knew we needed to get the ball to our three-point sharpshooter Allan Houston. But Houston couldn’t shake his defender in time so, in a panic, Charlie Ward passed it off to the next closest person– none other than Larry Johnson. At this point in my memory, the narration inevitably switches from my ten-year-old consciousness to Marv Albert, one half of the Knicks 1999 radio broadcast team and the quintessential play-by-play commentator in basketball history: “Johnson behind the arch. Eight seconds remaining. Hesitates. Fakes right. Fires!…”

Have you ever wondered what it would be like if everyone on the planet, or at least the country, did one specific thing all at the same time? Like if everyone in America made a phone call to the same number or if the whole world simultaneously flushed their toilets. That’s kind of what it felt like hearing this shot called over the radio. It was a millisecond of dead air with such profound anticipation it seemed the whole world was listening, the sort of moment of absolute silence when you subconsciously lean in towards the radio as if the motion will help you hear the news faster.

The eruption at the Garden was so loud we could barely hear Albert’s shouts of “YES! And the foul!” Johnson not only tied the game with a three-pointer, but with the completion of his foul-shot, he put the Knicks a point ahead of the Pacers with only five seconds left on the clock. It was one of those weird plays in professional sports that are about as likely as Elton John being elected president, but seem to almost always happen when the game is on the line, as if some sort of divine presence had suddenly changed the fate of the game. Larry Johnson certainly seemed to think so in his post game interview. Every other statement was prefaced with an “All praise is due to Allah.”

It wasn’t just our car that exploded when it happened: the LIE was clearly full of Knicks fans. Families giving each other high fives, hugs, drivers everywhere letting go of the wheel for an emphatic fist pump. I specifically remember these twenty-something year-old Italian guys in this beat-up sedan going nuts in the next lane, shouting out their windows, trying to start a “Let’s Go Knicks!” chant in the middle of a traffic jam.

That season our Knicks squad had character. We had class. We had moments. These guys weren’t just basketball players, they were Knicks. In fact, they weren’t just Knicks either, they invented the Knicks. These names Ewing, Johnson, Sprewell, Houston are the essence of New York basketball.

During my last trip to the Garden with my uncle, I couldn’t even name all five Knick starters without looking at my program. In ’99, I could have given you the both the assists and points per game for any single Knick, and if you needed any other stat I could have quickly checked my immaculate collection of Knicks basketball cards and given it to you. In short, I’ve long abandoned the team I used to love. Nothing is more excruciating than the feeling of utter futility inevitably arising after watching more than a couple minutes of Knick basketball. No longer do I harbor an irrational hatred of the Miami Heat, Alonzo Mourning, or any other Knick rival. And on top of that, I’m now old enough to realize the Garden is kind of a dump. These days, I can’t imagine a car ride where anyone in my family would voluntarily listen to the Knicks on the radio. It just wouldn’t happen.

Leaving the Garden after another Knick loss that night, I couldn’t help feeling a sort of hollowness. Nine years ago it would have been exhilarating just to see these guys take the court. Now I find myself wondering if I could ever forgive this sorry ball club. One thing is for certain, the next time I work up the courage to fish out my Ewing jersey and head to the Garden, I’ll be expecting their most sincere apologies. After all, this is New York basketball– we’ve got a reputation to uphold.

3 Comments

Adam

I feel like the new Yankee Stadium is going to be the same way… it’s a damn shame.

Anonymous

I couldn’t agree more. I went to the Nets-Knicks game today in Jersey. We lost.

Old school

If you think the Garden is a dump now, you should have seen in years ago. People used to bring nails and a hammer. They’d drive the nails into the wall to hang up their coats!