c/o Sabrina Ladiwala, Head Arts and Culture Editor

A new exhibition in the Ezra and Cecile Main Gallery, “fron/terra cognita + Hostile Terrain (HT94),” opened on Nov. 1, with a community workshop on Oct. 28 from 11:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. in Usdan Room 110 prior to its opening. Anchored by the Hostile Terrain exhibition and work, this gallery covers the harsh realities faced by migrants crossing borders.

As I opened the door to the gallery, I peered down a dark corridor into a room with a projector screen. All of the windows leading into the last room were blacked out so that the video playing would be more visible. I took a glance at the pamphlet and realized that four out of the seven pieces featured in the exhibition were videos. I turned left towards the main room of the gallery, figuring that I could watch all of the videos after looking at everything else.

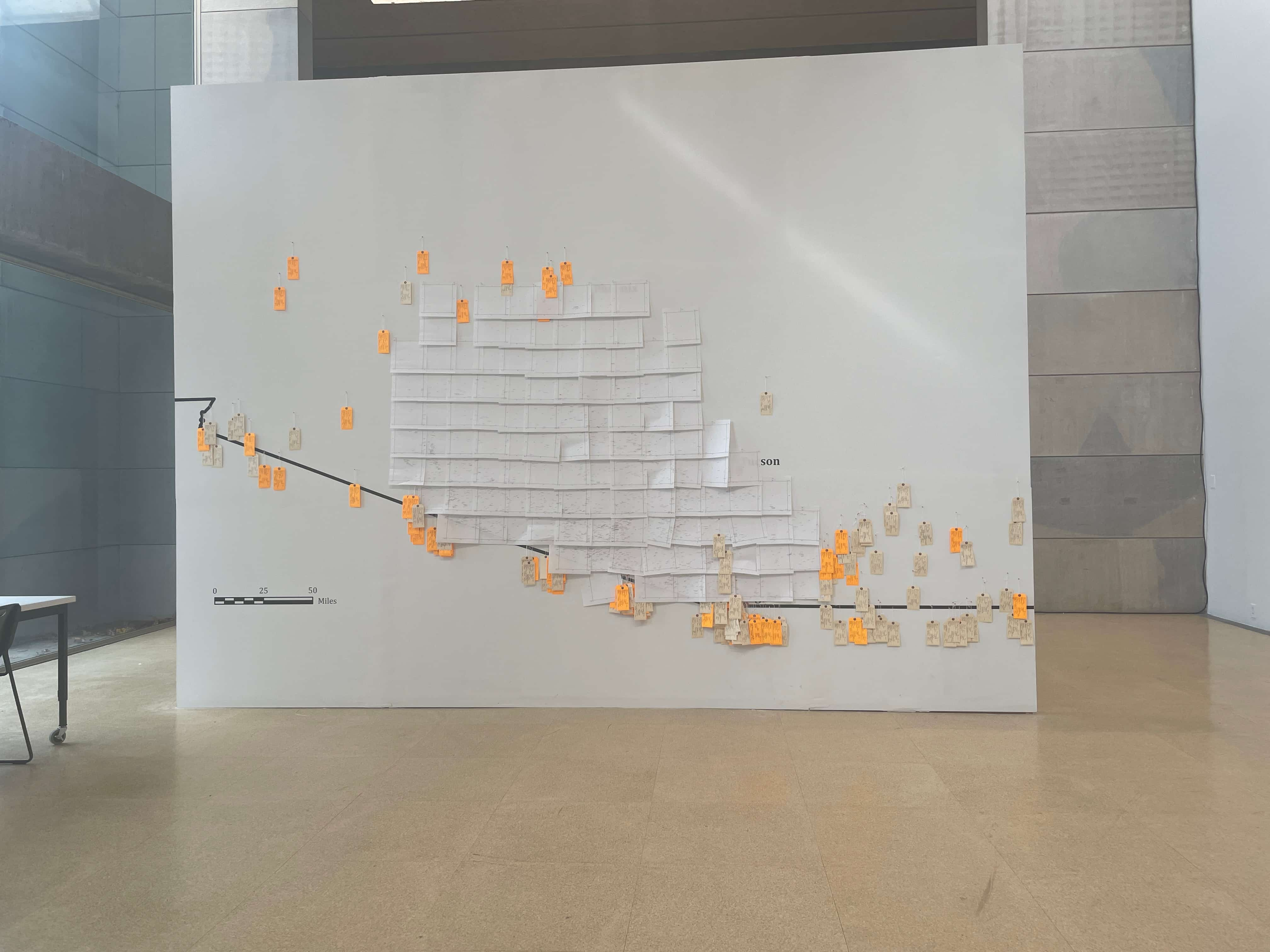

Even though the sun was shining through the windows, there was a heaviness that hung in the air. I was immediately drawn to the big map depicting the Sonoran Desert along the U.S.-Mexico border that was towards the back of the gallery. This was the Hostile Terrain installation based on the forensic anthropological work by 2017 MacArthur fellow Jason de León.

“HT94 is a visceral and visual documentation of migrant deaths along the US-Mexico border,” the pamphlet I picked up in the lobby read.

Pinned across the map were toe tags representing the people who had died while trying to cross this border. Each toe tag was one of two colors: manila, representing identified bodies, and orange, representing unidentified bodies. The manila tags had the names of the deceased written on them while the orange ones, obviously, did not. I can’t express how difficult it was to look at all of the names, and how much harder it was to look at the blank orange toe tags. This is often a side we don’t see about crossing the border and, while it was jarring to observe, this bluntness is so important and necessary to communicate.

Next to the map was a table with blank toe tags, papers with names and dates on them (some of the names were crossed out), and some pens scattered around. A separate piece of paper listed the significance of the exhibition as well as some instructions. They encouraged the observer to fill out one of the toe tags with the correct information and place them in a folder that lay next to the instructions.

“The physical act of writing out the names and information for the dead invites participants to reflect, witness and stand in solidarity with those who have lost their lives in each of a better one” read the pamphlet.

As I walked around the piece, I saw a TV mounted on the wall behind the map. It was playing a film that depicted panoramic views of the landscape and I immediately noticed how dry and barren the landscape was. Aside from a few bushes scattered around, the terrain was overwhelmed with rocky and mountainous terrain. Then the film cut to a plaque with the name “John Doe” engraved in the middle with a year written below. The camera zoomed out to show hundreds of plaques, stretching for miles, which was shocking to see.

c/o Sabrina Ladiwala, Head Arts and Culture Editor

On the right wall of the gallery were two additional artworks. The first one “Les frontières tuent: Bimbia/Limbé” by Cameroonian photographer Polo Free was a collection of 11 photos depicting what people left behind as they were forced to migrate to another country. While the images were neatly organized across the stainless white wall, they showed nothing but disarray. Pictures of shoes, bags, and boats strewn along the beach and left to disintegrate made me think about who these objects might’ve belonged to. What was it like to leave their home? Leave everything behind?

“Polo Free’s work, both here and in previous work around Tangier, Morocco, moves away from the spectacularizing effect of what is normally seen in representations of both enslavement and migration to remind us that they are/were both unfortunately and devastatingly everyday phenomena,” read the pamphlet.

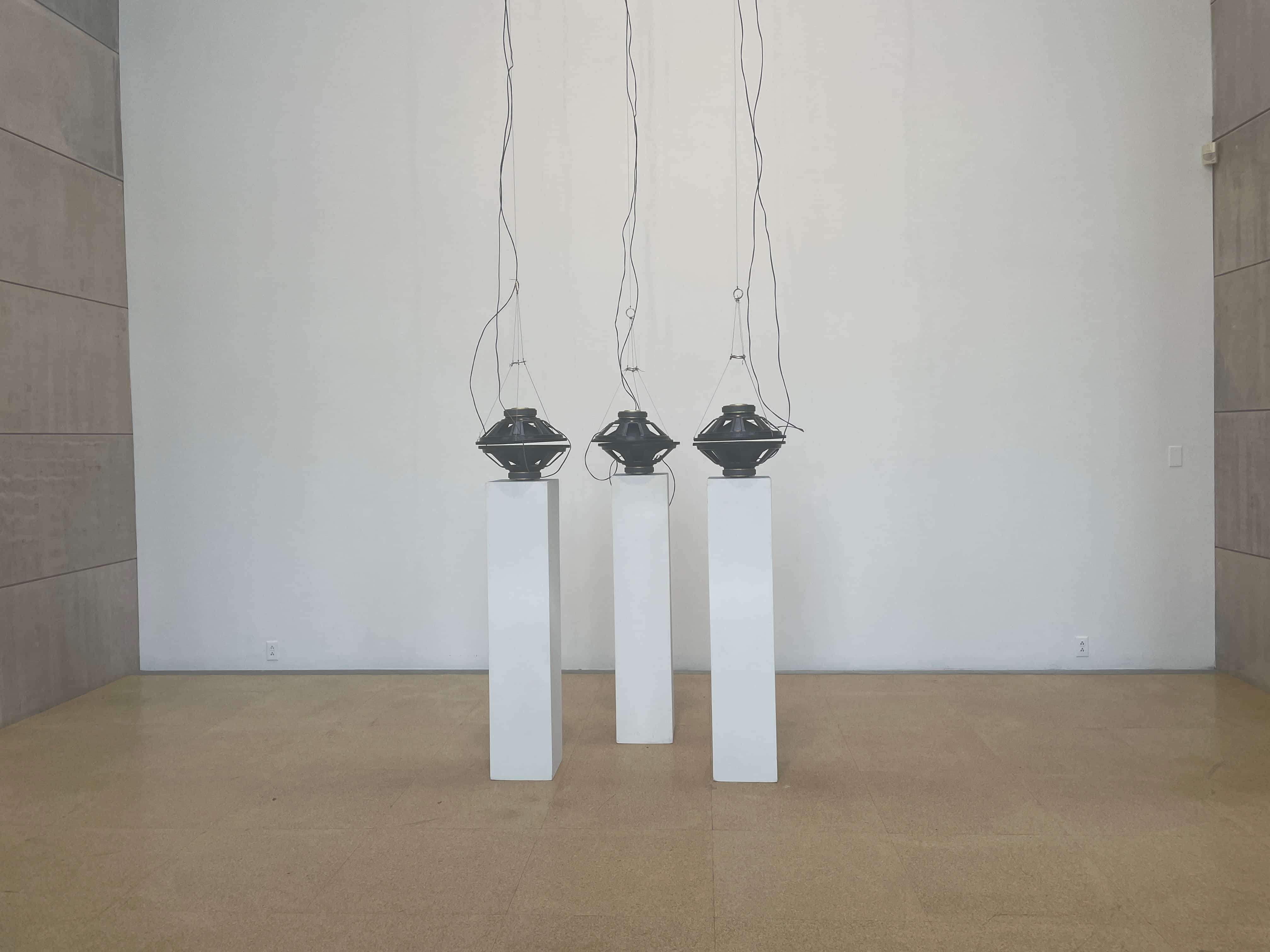

Next to “Les frontières tuent: Bimbia/Limbé” was “Lake of Flowers” by Yara Mekawei. Mekawei’s piece focused on sound. There were three bowl-like structures placed on white pedestals in front of the cement wall. Emanating from them was a humming-like sound that felt almost non-human. As I listened, I felt compelled to close my eyes and observe the soundscape created by this piece. While the humming was constant, I heard bells of different pitches intermittently dispersed in the background. They never took center stage, but added to the rich layers of sounds. I also found that, due to the echoey space of Zilkha, the “Lake of Flowers” piece was audible throughout the gallery, immersing me in the space and in the artists’ work.

c/o Sabrina Ladiwala, Head Arts and Culture Editor

There was a beautiful piece of writing by Mekawei on a plaque mounted on the wall to accompany “Lake of Flowers.” It spoke about migration in the context of moving through life.

“Migration from prime life to eternity started when I migrated from home to another land. The trial does not exclude anyone,” the plaque read.

I stepped away from the right wall and walked over to the opposite side, where a reading corner was set up against one of the windows. There was a bookcase displaying books including “Signs Preceding the End of the World” by Yuri Herrera and “Nomad Century: How Climate Migration Will Reshape our World” by Gaia Vince, all revolving around the migration of people. Something that fascinated me about this little space was the rather unusual seating options. There were white wall-like structures with holes cut out that one could crawl into. Additionally, there was a stool whose surface layer consisted of various patterns made from blue jeans messily stitched together. The circular cutouts were also lined with blue material, though it was soft and fuzzy like a blanket. While this corner wasn’t part of the gallery, it still maintained the theme of the exhibition.

After observing each piece in this part of the gallery, I made my way into the projection room. A video of the four film pieces was playing on a loop. When I took a seat, “4 Waters-Deep Implicancy” by Denise Ferreira da Silva and Arjuna Neuman was playing.

“[F]ragments, sounds, and stories help us convey the experiential moment of entanglement, or rather, they describe an entangled moment prior to separation, what we called ‘Deep Implicancy,’” read the pamphlet.

The 31-minute film used the image of water to capture this idea of entanglement. There were several short clips of different forms of water, which were juxtaposed with other images: the ocean at high tide covering a pink-sand beach, lava running onto snow, waves crashing into jagged rocks during a storm. These images were accompanied by single lines of text appearing on the screen.

“Transformation rumbles elemental leaving ethnic stripped of value…And the human inseparable from all matter,” was one of the lines displayed.

These words connected the images to the overall theme of the film, allowing viewers to think about the deep connection between earth, water, and humans.

The next film “Bab Sebta Cueta’s Gate” by Randa Maroufi displayed how vendors cross the border between Morocco and Spain.

“The border of Bab Sebta is the scene of a traffic of manufactured goods, sold at discounted prices,” read the pamphlet. “Thousands of people cross this border every day, carrying enormous packages of goods.”

The viewer can observe the dynamics of movement of the vendors and the police officers. The initial image is a birds-eye view of the border. We see people sleeping on the pavement with only cardboard boxes as a barrier. Huddled together, they wrap themselves in blankets to keep warm. In opposition to this image, there are police officers doing push-ups on the pavement, not too far from those trying to get some rest. The film then cuts to the vendors urgently strapping merchandise to their backs and legs in order to cross the border. They then move into a single file line and place boxes on a conveyor belt for border security screening. All this while, the narrator dictates what’s going on in Spanish. She says that if you fall, no one will help you get up, both literally and metaphorically, emphasizing the cutthroat environment displayed in the film.

After Maroufi’s film, “The Invaders” by Ghita Skali began to play. This nine-minute and 51-second video takes the concept of a 1970s American science-fiction television series about aliens and applies it to migrants.

c/o Sabrina Ladiwala, Head Arts and Culture Editor

“In the nineties, the French humorists Les Inconnus remade the show and replaced the invaders with migrants living in France…This video is a remake of this remake wherein the world went upside down and the attraction from the Global South to Europe was also reversed,” read the pamphlet.

This video shows white people dressing up as locals in Morocco and influencing the main characters. Set in an Islamic village, one of the main characters who welcomes in an invader ends up dying by consuming and choking on pork. This highlighted the idea that invasions can happen subtly and without people really taking notice.

The last film, “The Smuggler, Tangier” by Yto Barrada, was a silent film that depicted a woman who makes trips to the Spanish enclave of Cueta to smuggle back fabrics ordered by shop owners in Tangier.

“Because she is an older woman, tax and customs officers usually do not search inside her coat at the border,” read the pamphlet. “Against the backdrop of black curtains, T.M. demonstrates how she wraps her body with heaps of fabric, and concludes with slipping on her long djellaba, to cover the ‘tax-free’ smuggled goods entirely.”

Because it was a silent film, I could really focus on the movements of the woman. I saw how she took layers of fabric, draped them across her back, and tied them with a plastic strap. It was really hard to watch her do this over and over again, each time the load on her back and waist becoming heavier and heavier. It was especially difficult to see that she needed her son’s help to wrap fabrics around her ankles and then put her large black coat over everything.

This exhibition gave me insight into the lives of migrants. From loading heavy merchandise on their backs to crossing the rocky terrains, their struggles and stories are so important to listen to and share with others. If you have a chance to visit “fron/terra cognita + Hostile Terrain (HT94)” before it closes on Dec. 11, I highly recommend you do so!

Sabrina Ladiwala can be reached at sladiwala@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed