When we meet William Tell (Oscar Isaac), the protagonist of “The Card Counter,” he exudes precision. William is a man in control. His hair is precisely slicked back, his clothing is a stark, pressed uniform of gray and black formalwear, his manner is quiet and calculated. He has spent many years in prison for an initially mysterious crime and upon returning to the world, he has continued to live a regimented and isolated life, having taken to the routine of incarceration.

By day, William travels across the country visiting casinos, using skills he taught himself during his stint in prison to win money in poker and blackjack games. By night, he retreats to lonely motel rooms, binding every piece of furniture in plain white cloth for reasons which we are never quite told. Perhaps he aims to make each room indistinguishable to ease his mind while on the road, perhaps he wishes to leave no trace of his presence. William never bets large sums of money, instead choosing to gamble on modest amounts in the three-figure range, a way of keeping attention away from his well-honed card counting abilities.

At one casino, William stumbles upon a private security convention and sees a lecture delivered by Major John Gordo (Willem Dafoe), a hard-nosed military man turned security consultant. Leaving the lecture, William is confronted by a young man named Cirk (pronounced “Kirk,” but spelled with a C, as he informs everyone he meets). Cirk (Tye Sheridan) identifies William as a former soldier who took part in the systemic torture, dubbed “enhanced interrogation,” of detainees at the American military prison at Abu Ghraib, Iraq in the early years of the War on Terror. It was for this, we realize, that William served time.

William’s nightmares, filled with brutal images and chaotic sound and filmed in an upsettingly immersive fisheye lens, confirm that he remains haunted by his actions. These scenes, filmed as if drifting through the prison complex’s horrors on a track, give a sense of loss of control and moral powerlessness by William that he has since sought to reclaim by tightly ordering his life.

Major Gordo, Cirk has discovered, oversaw Abu Ghraib’s torture program, but never faced consequences, leaving his young subordinates, including William and Cirk’s father, out to dry. While William seems to have repressed his past violence, Cirk’s father took out his trauma on his wife and son before eventually taking his own life.

Here, William finds himself at a crossroads, pulled from his life of joyless gambling and itinerancy. Cirk offers a chance for revenge, to address the sins of his past, as the young man plans to kidnap Gordo and exact upon him the tortures he inflicted on Iraqi prisoners. Meanwhile, La Linda (Tiffany Haddish), another traveling gambler, offers William a chance at a real future, as she argues that his skills could allow him to go professional and join her community of investor-backed cards pros.

“The Card Counter” was released on the weekend of the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, a date that feels intentional for a film that interrogates a conscience haunted by the atrocities committed during the War on Terror. Throughout his decades-long career, writer-director Paul Schrader has continuously examined the traumatized psyches of lonely men, from the violent loner Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) in “Taxi Driver” (1976)—which Schrader wrote for longtime collaborator Martin Scorcese, who produced “The Card Counter”—to the climate change-tormented soul of Pastor Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) in 2017’s “First Reformed.” As in “First Reformed,” his acclaimed previous film, in “The Card Counter” William represents another opportunity for Schrader to tie a character’s personal demons to that of the broader society.

One of William’s frequent opponents, a Ukrainian-born player who goes by “Mr. USA,” wears a garish star-spangled outfit, with an entourage that chants “USA” when a game is going well for him. After a victory, Mr. USA goes to live it up with his crew. William, who personally carried out America’s dirty work, goes back to his featureless motel room, drinking and journaling alone before another night of haunted sleep. His spartan existence seems itself a form of self-flagellation in which he deprives himself of indulgence to atone for his sins.

Central to the power of “The Card Counter” is Isaac’s tour de force performance as William. He is a man of few words, and in the hands of a lesser actor, his cold exterior and bizarre habits could make the character come off as an alien or a serial killer. But Isaac imbues William’s eyes with a deep sense of warmth, continually reminding the audience that, behind that precise facade, is a human with feelings.

We see William become a father figure to Cirk, hoping to keep the young man off the path of violence as he simultaneously realizes his passing friendship with La Linda could be something more. In these moments, Isaac keeps the viewer hoping that, even with his horrific past, William has goodness buried somewhere deep. But Schrader keeps us on our toes, and as pressure mounts, we are also served a chilling reminder that William never lost the ability to slip into the mode of an icy torturer.

“The Card Counter” is a haunting, grim film. Even its visuals render the typically glamorized world of casinos equally claustrophobic and inhumane as the prison in which we first meet William. Despite its thematic focus on acts of violence, its tone is slow and contemplative, rather than action-packed. Schrader cares far more about the psychological fallout of violent acts than the cinematic excitement derived from their depiction.

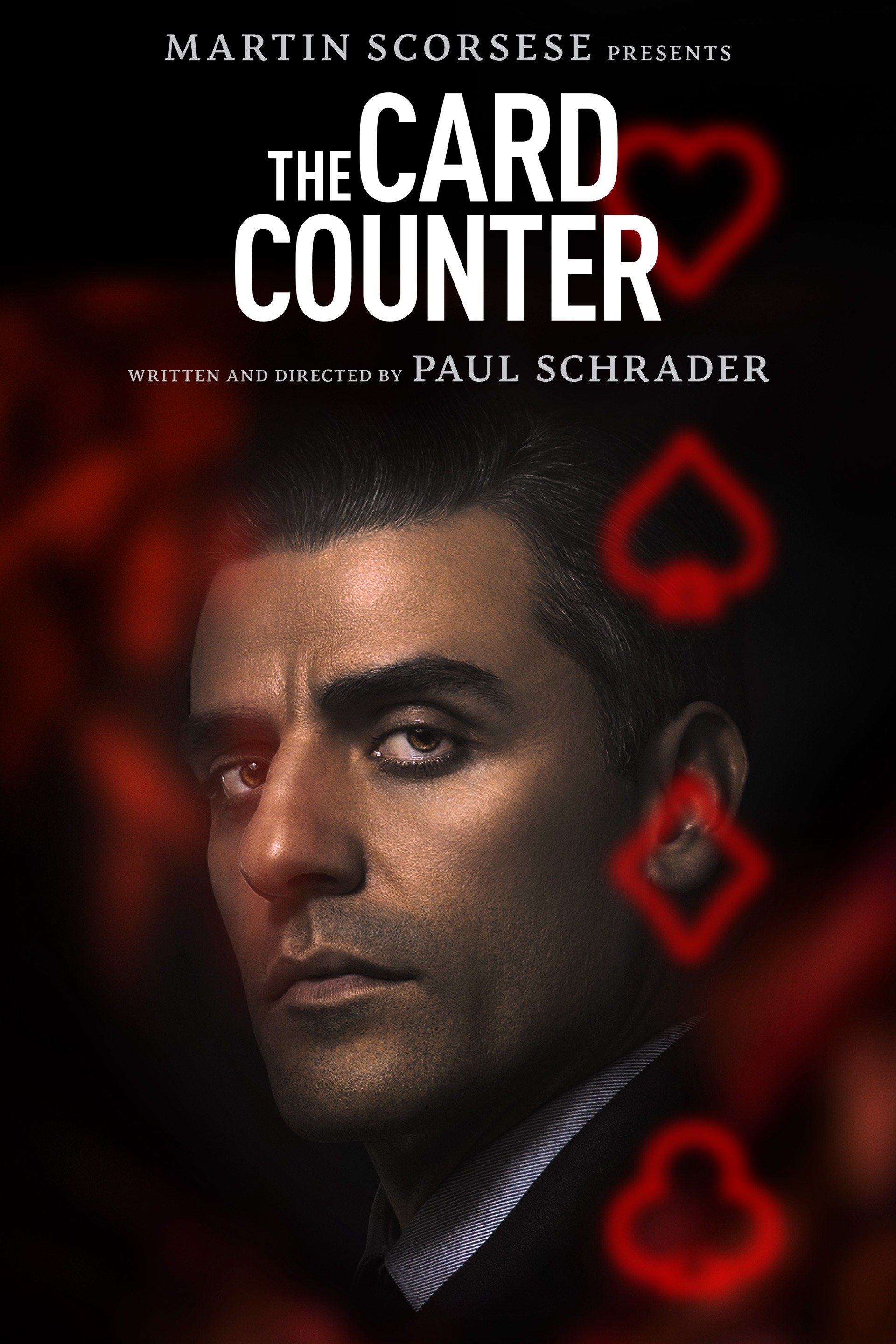

Perhaps these elements factor into the film’s lukewarm audience reception. Despite a high critical score of 88% on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film’s audience score is less than half that, at 42%. A lackluster marketing campaign, which was focused on playing card imagery and Isaac’s visage, might also have led moviegoers to expect something closer to the high rolling thrills of “Ocean’s Eleven” than the mournful, traumatized note “The Card Counter” hits. But on its own terms, “The Card Counter” is an impressive work, an intimate, dark character study that interrogates the cyclical nature of violence, and the struggle and question of what it means to make things right.

Oscar Kim Bauman can be reached at obauman@wesleyan.edu

Comments are closed