“Picking up fragments of my existence, / Scotch tape provides a temporary fix / that I shape with twisted scissors,” sing Yusuke Awazu and Keisuke Tanaka in “Vague Ridgeline.”

Not only did Awazu and Tanaka compose the song’s music and lyrics, they also performed it live last Friday at the University’s Center for the Arts (CFA) Theater, as a part of the dance performance “Fruits borne out of rust.” The duo sang the infectious and disturbing melody of “Vague Ridgeline” entirely in Japanese, sounding as if The Cardigans and Mitski had finally decided to collaborate.

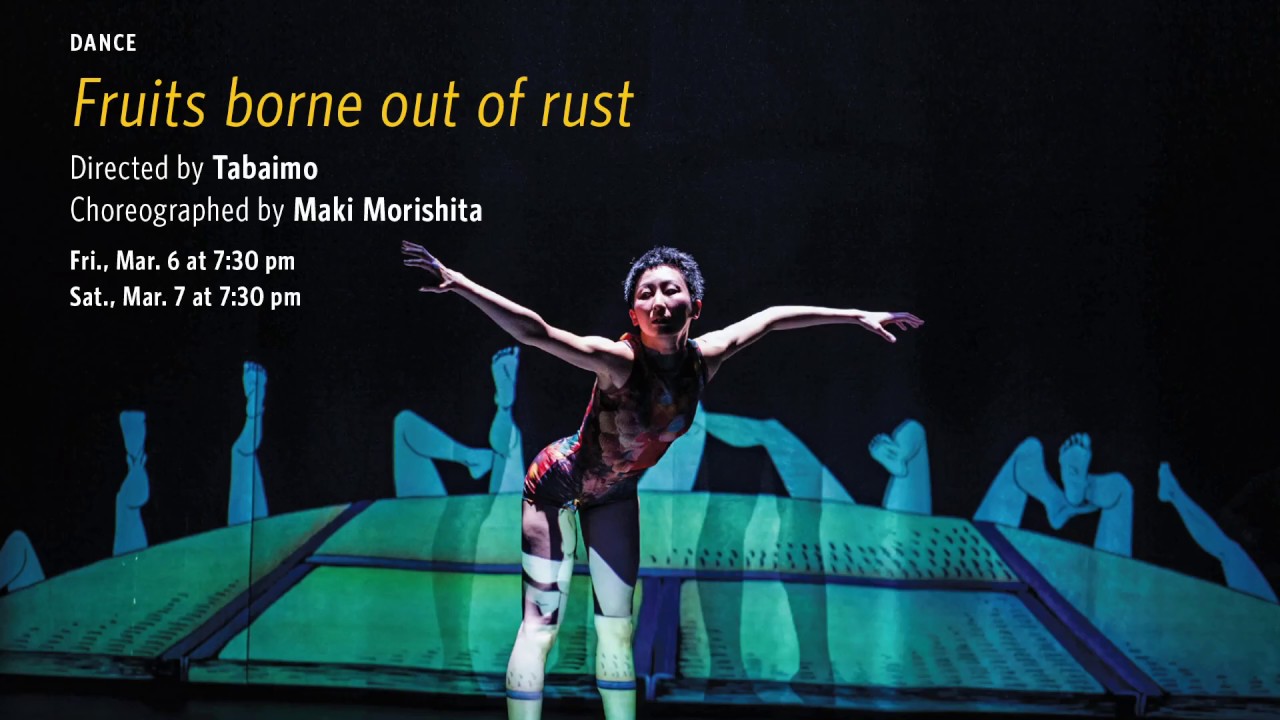

On stage, donning an outfit stained with red paint splotches, dancer Chiharu Mamiya transformed her body into a series of sharp edges, jutted elbows, and sudden falls to the ground. It was an experimental and modern dance that could have only come from the distinctive voice of choreographer Maki Morishita. As Mamiya’s highly structured movements continued, giant pairs of scissors started falling through the air. At least, it looked that way: three giant projectors screened enormous drawings of the scissors on a scrim behind Mamiya, sometimes placing their sharp edges on her body. The person behind these drawings was the animator Tabaimo, a multi-faceted artist who performed many roles throughout the production. Not only did Tabaimo draw the scissors, but she also co-conceived the project with Morishita, directed everything onstage, and watched the action from in front of the stage—all while simultaneously playing a xylophone.

The constant collaboration between these five Japanese artists—musician, dancer, choreographer, and animator/director—make “Fruits borne out of rust” an immersive entertaining experience. Throughout the show, different elements of performance bounce off each other and spin out into playfully experimental journeys. But these journeys are made up of multiple scenes of distress and existential dread that do, in fact, seem cut by twisted scissors. It’s the painful specificity of the experiences that these artists speak to that drives their investigations from playful examination to profound reflection.

During a visit to the class “Theater/Drama Traditions of China and Japan,” Tabaimo and Maki Morishita discussed their creative process with students. Tabaimo, known for her video installations in art galleries, and Morishita, whose modernist dance has been set to Beethoven and is often performed by non-dancers, both see themselves as different from the traditions of their respective genres. Tabaimo initially stumbled upon video installation as a means of distinguishing herself in art school, before realizing it didn’t necessarily have industry-level applications. Morishita used dance as a communication tool while she was constantly moving as a child, noting that her friends would often remark, “Even when you’re talking, it’s like you’re dancing.” She saw dancing as a form of self-expression and only later saw her work categorized under the modern dance genre. When Tabaimo and Morishita met, they discovered the many similarities between themselves—they both were born in the same place, have three sisters, and have the same blood type—and embarked on an organic collaboration that in retrospect seemed like a fateful match.

After listening to Awazu and Tanaka’s “Vague Ridgeline,” the duo picked up on the two final lines of the song: “May the flowers bloom where the tears shall fall // May the fruit borne out of rust ripen and burst.” It seemed to capture both artists’ obsession with embodiment, aging, and instability while also gesturing towards artistic creation and resilience. “Fruits borne out of rust” was the metaphorical fruit borne out of their collaborative grappling with these dark themes, and since 2013 the project has itself been growing and changing with each iteration. Previous incarnations featured three dancers to reflect the three sisters of both artists. Morishita particularly emphasized that her choreography adjusts to each dancer inhabiting the role. For example, because a previous lead dancer performed a year after giving birth, Morishita made sure to reflect on the state of that dancer’s body and how it impacted the themes of fear, weariness, and withdrawal in the show.

The North American tour of “Fruits borne out of rust” features Chiharu Mamiya as the only dancer, and leans even more heavily into Tabaimo’s animation to tell a cohesive narrative and create huge scenography on stage. The show consists of a series of small scenes that cyclically reveal a woman struggling with her position in the world, and her position in her own body. In an opening prologue, Tabaimo draws on a whiteboard and steps offstage to play the xylophone while a stagehand slowly, deliberately erases the whiteboard, destroying Tabaimo’s carefully crafted picture. Following this, Mamiya performs to a song behind the the whiteboard, the audience able to see her legs, while a projector displays a dancing torso onto the whiteboard. The synchronicity, or lack thereof, between the torso and legs is not only technically impressive, it’s also absorbingly funny, until the moment when the two parts of the body seem to be fighting each other and a personal struggle with the body seems to unravel.

The rest of the show mines this unravelling through continually evocative stage pictures. During the scene “a window woman,” Mamiya mimes fixing her face in the mirror as projected scribbles are cast upon her body, and her body is trapped within a cramped room. As one of the floorboards is released in the animation, Mamiya seems to magically disappear into the ground. Only later is it revealed that Mamiya slipped through an opening in the projector scrim, and is seen undressing with lights that go behind the scrim.

This kind of surreal relationship between Mamiya, Tabaimo’s animations, and the different possibilities opened up by projections constantly provides delight and occasional anxiety for the audience. In “Box and Bird,” Mamiya at first stands in front of the projector, casting her dancing shadow onto the skim, but later is dwarfed by Tabaimo’s animation, which places her in a cage with a larger-than-life bird flying around fighting her. During “Vague Ridgeline,” Mamiya witnesses multiple disembodied legs moving around her, and at the end she finally decides to become one of them, moving her legs as if she’s copying the image she’s been constantly reckoning with. During “Next Door,” an extended imagining of a next-door neighbor that has never been met, a giant animated lightbulb swings back and forth on the stage, and the stage lights illuminate the musicians Awazu and Tanaka on each side of the stage accordingly.

Projections and screens are by now common in performance—the “West Side Story” revival currently up on Broadway features a giant screen as its entire backdrop—but rarely do the performers and animations have such an intimate relationship. By having Tabaimo’s animations influence Morishita’s choreography and vice versa, it seems as if the animation’s strange repeating imagery—giant eggs, birds, body parts, rotating boxes, beating hearts—is bursting from the tortured mind of Mayima, and also trapping her in frightening situations. Tabaimo and Morishita state that they develop their work within the same space, and the result is that their work seems to seamlessly interact as if in a carefully stylized dance itself.

The fusion of these different elements of performance is only clear in the few times they are isolated from each other. There were a few moments where animation fell away, and we were left to listen only to the musicians performing a duet of cascading chords on the piano. But even more disturbing were Mayima’s solo scenes, when the visuals and music cut away and we were left with her alone onstage, spinning around in circles, exhausted, her breathing heavy and labored. During an extended monologue preceding “Vague Ridgeline,” Mayima spoke in both Japanese and English, frustratedly trying to explain the pain she was feeling through telling a story at a hospital, screaming out, and calling attention to her strange moods.

“It’s hard to describe,” Mayima said. “Maybe with fingers…better if you do it.”

She waved her fingers to communicate her strained feeling, and then began moving her entire body. Stranded with just herself, stranded with only language, Mayima is unable to fully communicate the depth of desperation she is feeling. It’s only when all the elements of performance come together, aided by the power of animation, sound, lighting, dance, and music, that she is able to fully embody exactly how it feels to be herself in a moment.

It seems as if the collaboration between all five Japanese artists, led by Tabaimo and Maki Morishita, functions in a similar way. Although they are able to convey intense feelings separately, it’s only when all of their methodologies come together that the audience feels pulled entirely into a different world. This is especially true of the final scene of “Flowers borne from rust,” in which the shadows of Mayima’s hands represent growing flowers, until a constantly moving animation and churning soundscape stimulate a meditative trance for the audience, ending in the growth of flowers all over the stage. Looking at the performers bow, it seemed as if they were worn out. Having this level of technical harmony within a dance show, with multiple performances happening concurrently and always influencing each other, must be exhausting. But as Tabaimo herself notes, “Rust is the reaction of iron undergoing oxidation in effort to obtain a more stable state of matter.” At the end of “Fruits borne out of rust,” the performers have undergone an intense state of duress only to arrive at a quiet, lovely state of rest.

Nathan Pugh can be reached at npugh@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed