William Halliday, News Editor

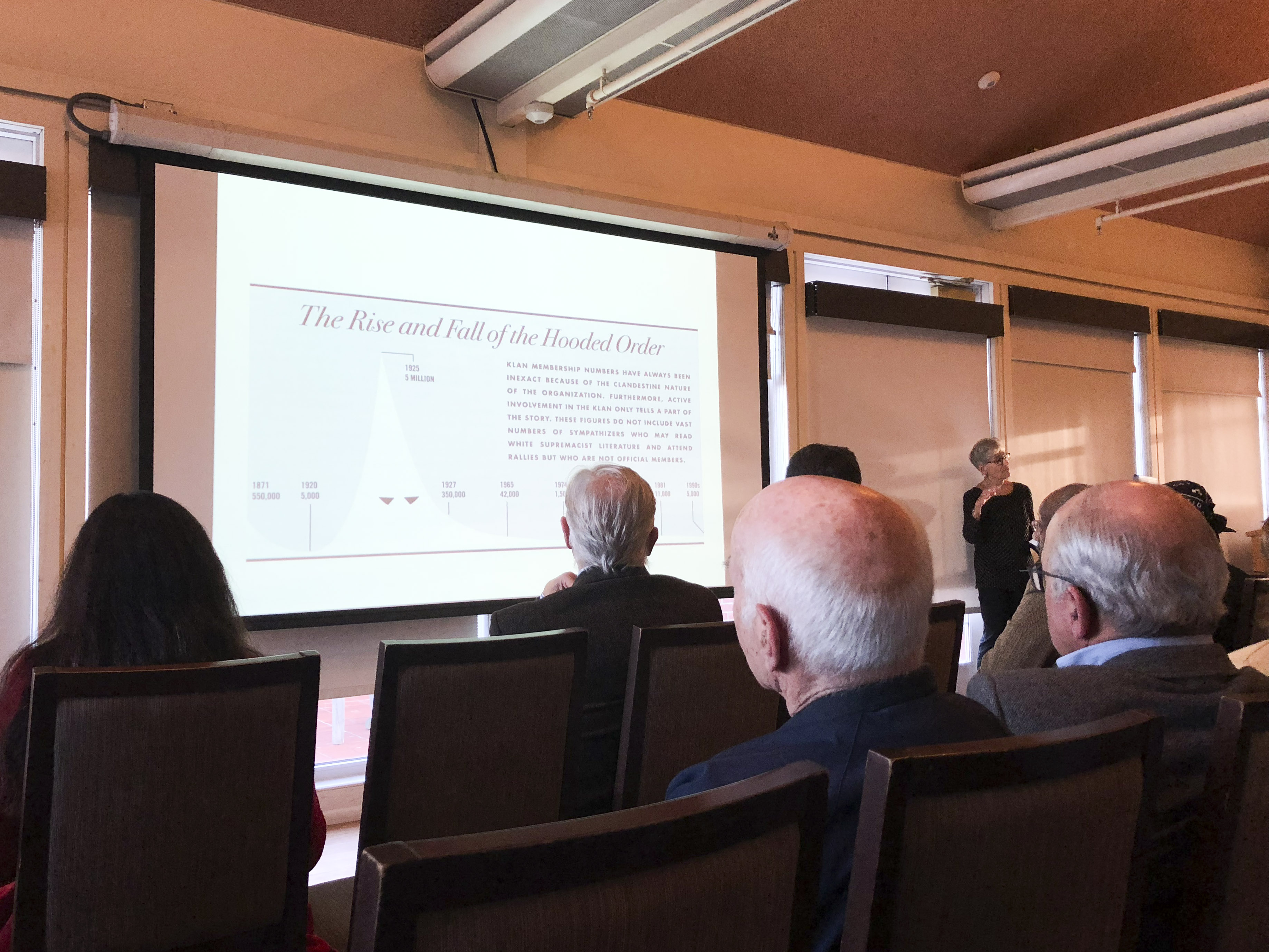

On Tuesday, Oct. 16, Professor of History at NYU Linda Gordon delivered the third annual Meigs Distinguished Lecture in U.S. History to a packed room in Allbritton. The talk, titled “Populism and Bigotry: Lessons from the 1920s Ku Klux Klan,” was based on Gordon’s new book, “The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition.”

Gordon, who taught at UMass Boston and University of Wisconsin, Madison before relocating to NYU, has authored eight books on a variety of topics ranging from the history of birth control in the U.S. to the Cossack rebellions in 16th-century Ukraine and the American welfare system. She has won the Bancroft Prize for best book in the field of U.S. history twice for her books on the 1904 Arizona orphan abduction and photographer Dorothea Lange. With this diverse array of scholarship under her belt, Gordon published “The Second Coming of the KKK” as an exploration of the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. In her book, Gordon traces how the KKK, which has its roots in the the 1870s South, experienced a boom in the 1920s, primarily in states above the Mason-Dixon line.

Professor Gordon began her lecture by highlighting that KKK membership was actually strongest in these northern states. She described the growth of this “Second Klan” as originating from both the increase in immigration that began in the 1880s and the post-WWI resentment of political dissenters. Espousing the belief that white Protestants were the only “true Americans” and that America’s destiny was to be a white Protestant nation, KKK members organized to protest the racial and religious diversity they saw as polluting the “purity” of the country.

Throughout the talk, Gordon highlighted the resentment that the KKK harbored towards Jews and Catholics, who they believed were conniving to subvert what they saw as “traditional America.” She related the fact that some KKK members clearly never interacted with anyone from these religious groups to the general susceptibility of large groups to hating certain groups even when members lack experience with them.

“In Oregon, the percentage of Jews in the population was 0.03%,” she said. “The percentage of Catholics was a little bit larger…. Most of the people who were made to believe that these Jews and Catholics were trying to destroy America had probably never met a Jew or Catholic. And there’s something extremely important about that, that in many situations it’s possible to rev up that kind of hatred in absence of any actual experience.”

This hatred went hand-in-hand with conspiracy theories about Catholics and Jews immigrating to the U.S. in order to stage some sort of overthrow of the government. Gordon stated that KKK members believed that Catholics could not be loyal to America because they were loyal to the Pope and spoke about their theory of a Catholic plot to take over the country.

“[They believed that] these immigrants were coming to America, not because they were poor or they were looking for a better life, but they were coming because the Pope ordered them to come,” she said. “And he did this to have them get them settled as in what espionage stories are called moles. They would live incognito in the U.S., waiting for the order to take over.”

She then highlighted the involvement of the police force in the Second Klan, stating that the largest occupational category of Klan members was law enforcement officers. Police departments would “deputize” Klan members and encourage them to engage in vigilantism. Since this rise in the KKK was occurring during the Prohibition Era, Klan members raided saloons and intimidated those they suspected of engaging in the production and sale of alcohol. They also racialized the anti-Prohibition activities they saw as undermining America’s social order.

“In their view, the only people who drink are Catholics and the only people who bootleg are Jews,” Gordon said.

One of the more surprising points of the lecture came when Gordon discussed the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, or the WKKK, which counted some 1.5 million members at its peak. The women in this group represented a tension between a steadfast belief in conservative gender norms and the desire for political participation.

The chapter of her book in which Gordon discusses the WKKK and what she calls “Klan Feminism” has gotten her the most feedback from readers because it pushes back against the all-encompassing progressive values that many ascribe to feminism.

“There’s a chapter in my book called ‘Klan Feminism,’ and it’s the chapter that I predicted that I would get the most flak about because a lot of people want to think that to be a feminist you have to be progressive on all sorts of other issues…. Not so,” she said.

While espousing hatred towards racial and religious groups, members of the WKKK fought for political, social, and economic rights for women.

“One female Klan minister printed the famous 1848 Declaration of Sentiments, the document that began the women’s rights movement in the 19th century,” Gordon said. “She called for equalizing inheritance and divorce rights. She called for maternal custody of children…. Furthermore, many Klanswomen supported women’s economic independence.”

Gordon ended her lecture by discussing our understanding of “populism” today and how we should view the rebirth of the KKK in the 1920s. She thinks of populism as a political buzzword that is not usually accompanied by any substantive information and discussed how we tend to associate it with movements characterized by hatred and bigotry. She spoke about what historians think of as the original populist movement in the 1890s that fought for farmers and industrial workers, supported unions, and criticized Wall Street for cheating the American people.

“In a way, I hate to see that term of populist so transformed,” Gordon said.

She now sees the term used exclusively in an pejorative way, with a separation between right-wing and left-wing populist groups. Gordon has trouble finding any left-wing populists, though, and stated that she does not see Bernie Sanders as a populist.

Concluding the talk, Gordon stated that the Klan’s “populist” claim of advocating for the common people was utterly false.

“Even for white Protestants, this claim was entirely spurious,” she said. “The Klan never endorsed any policies that would have benefited the common people. It never challenged people that wielded economic power. On the contrary, it respected the very rich and honored the profit motive because the profit motive is what made America great.”

After the talk, Chair of the History Department Demetrius Eudell commented on what struck him most about Gordon’s research.

“The aspect of her talk which most struck me was the corporate nature of the KKK,” Professor Eudell wrote in a message to the Argus. “To join the group, one had to pay membership fees, and also pay for all the accessories, which could be expensive, as one could not purchase imitations.”

Ronald Kelly ’19, who attended the lecture as part of a course taught by Eudell, spoke about his personal reactions to Gordon’s talk.

“I think as a black man I’ve never been exempt from these kinds of histories—learning about the ways black people are and have been oppressed in this country, from lynchings and the Klan to workplace discrimination, was literally part of my upbringing,” Kelly wrote in a message to The Argus. “I’m also a southerner, which means that almost every place I’ve ever lived has been a site of historical racial violence, including one of the the last mass lynchings in America, which happened in the 40s in the county I went to high school in.”

When asked whether Gordon’s section about the WKKK surprised him, he stated that there was nothing surprising about such a strong female involvement in the movement.

“White women have always been the backbone of American white supremacy,” he wrote. “That didn’t surprise me in the slightest. What surprised me the most was that the contingent Gordon discussed called themselves the Klan at all—despite publicly disavowing violence…they still projected images of anti-black and anti-Semitic terrorism representing activities in which, presumably, they almost never participated. It shows a remarkable ability on the part of ‘civilized, urban’ white people to appreciate and appropriate the very barbarism they claim to despise in their rural comrades.”

Lindsay Zelson ’19, a History major, also attended the lecture. She spoke about what stuck with her from the talk and how she now thinks differently about the history of the KKK.

“Some important and, I think, little-known facts that Professor Gordon mentioned were that the KKK in the 1920s directed a lot of their hateful rhetoric at Catholic and Jewish communities, and that the KKK at that time was a non-violent fraternal organization that used direct threat and political lobbying,” she said. “I think recognizing that the KKK in the 1920s did not use the horrific forms of violence that they did against Black communities in the 1800s inspires us to ask more nuanced questions about the KKK’s enduring influence on American society.”

William Halliday can be reached at whalliday@wesleyan.edu.

Comments are closed