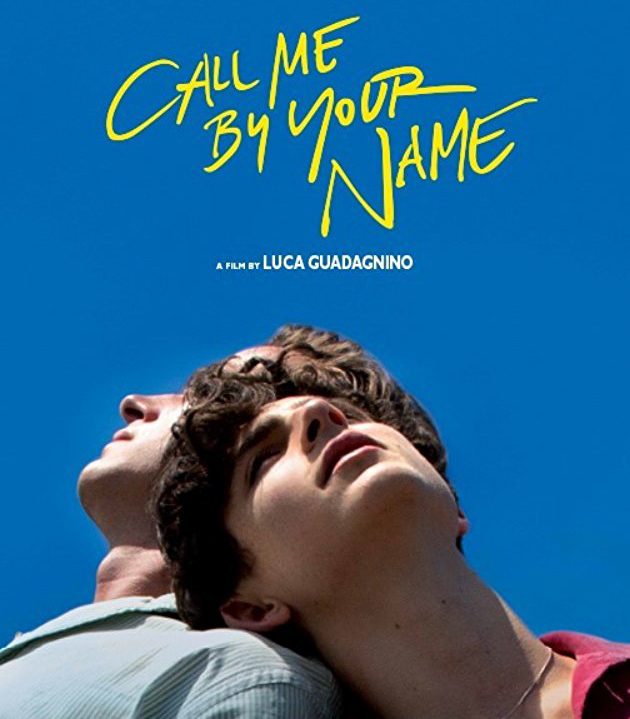

c/o imdb.com

Luca Guadagnino’s “Call Me By Your Name” is a romance film about the love between a 17-year-old boy, Elio (Timothée Chalamet), and a 24-year-old graduate student, Oliver (Armie Hammer), who is hired as an intern at the northern Italian villa where Elio and his parents spend the summer. Thus far, the film has received some eye-popping reviews: Manohla Dargis of The New York Times called it a “ravishment of the senses.” Justin Chang of The Los Angeles Times affirmed its status as “a new coming-of-age classic.” Perhaps most affirming is the headline published by Vulture: “Call Me by Your Name Is a Masterpiece.” In a world awash with throwaway Hollywood blockbusters and mediocre Oscar winners, Guadagnino’s film lives up to the hype—for the most part.

The movie, an adaptation of Andre Aciman’s novel of the same name, is a pastoral, set on a centuries-old villa in the northern Italian countryside. Its earliest moments prime a languorous, recollective quality when the words, “summer 1983, somewhere in northern Italy” flash onto the screen in lazy cursive. But rather than wallow in hazy nostalgia, cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom’s camera fixates on enlivening details. Rarely has a movie evoked a breezy summer afternoon, or any atmosphere, for that matter, so convincingly. A sensuous immediacy permeates every close-up and every sound, rendering the film a joy to watch and hear.

Chalamet and Hammer deliver expert, complementary performances. The physically imposing Hammer makes brisk, arrogant movements, gluttonously slurping down egg yolks and apricot juice. Hammer usually exits these scenes with an abrupt “later.” The camera tends to approach him from below, treating him as though he were one of the Greek sculptures that Elio’s father spends his time studying.

Chalamet, on the other hand, grows into his character, Elio, building layers of teenage anxiety and restlessness through smirks, half-smiles, and disarming moments of sincerity that culminate, along with the film itself, in two shots. In the first, Elio cries in the passenger seat of his mother’s car as she drives him home from seeing Oliver for the last time. Then, in the second, the final shot of the movie, he watches a fire burn in the dining room fireplace and cries, letting himself feel the sorrow and desperation of young love lost. Both of these expressions communicate more emotion than most dialogue could, although James Ivory, who wrote the film’s measured script, might disagree. Ivory shines among the movie’s many talented contributors, particularly in a beautiful monologue from Elio’s father (a brilliant Michael Stuhlbarg).

Apart from its emotionally rich finale, the film lingers in the placid realm of youthful, carefree summers and lighthearted romances, particularly during its first half, in which scenes rely more on sexual tension than actual conflict to advance the story. However, in a movie about queer love, this is welcome and almost jarring in its contrast to many movies that only star gay characters as exceptional heroes, dying of diseases, or getting beaten up. Elio and Oliver are just two people in love. Why should we expect them to be anything more?

Some of the film’s choices don’t stand up to inspection as easily, such as the socioeconomic status of its main characters. Elio and his parents spend their holidays in a beautiful and tastefully decorated, high-ceilinged villa, equipped with a full-time chef and a groundskeeper. Elio’s father is a professor of classics, his mother a translator, placing them firmly as intellectual and economic elites. Why? Did Guadagnino choose this setting purely for its aesthetic beauty? Did he make his characters rich only because he wanted to shoot his movie in a beautiful house? Elio’s parents, in the end, prove to be accepting of their son’s sexuality and his relationship with their employee, providing a startling open-mindedness, especially given the stigma of the time period. We have little choice but to infer that less intellectually elite people would not have been so accepting of their gay son, a position that implicitly vilifies lower social classes and glorifies more elite ones.

The film approaches the subject of politics asymptotically, without ever fully engaging it. Twice, in a panning shot of a town square, the camera hovers in front of posters tacked onto the walls urging citizens to vote for the Italian Communist Party and the Socialist Party. In another scene, two friends of Elio’s parents argue about politics over lunch, but the conversation is cut short when Elio gets a nosebleed. These out-of-place details in a film so unconcerned with the world outside of its idyllic setting suggest a sense of guilt on the part of the filmmaker toward his disengagement and portrayal of rich people as those most capable of goodness.

It’s also wholly unclear why the film was set in Italy, as none of the central characters speak much Italian, and the film does not explore issues specific to Italy. Despite the fact that the director is Italian, the film would not be at all altered if it were set in another country. Here, we see a film that follows in the footsteps of big-screen features like “Roman Holiday” and “Eat, Pray, Love” in exploiting Italy’s natural and human-made beauty, setting it as a playground for these wealthy characters without taking the time to engage with the nuances of the country and its people.

Still, these faults are small missteps in a movie that otherwise features virtuosic direction from Guadagnino and brilliant performances from its cast. The humanity that soars from its details—from its characters’ gestures, sighs, and tears—is undeniable and hard not to love.

Matteo Heilbrun can be reached at mheilbrun@wesleyan.edu.

-

creepingdoubt