c/o William Halliday, Photo Editor

The modern education system is a technocratic capitalist’s dream. Students are increasingly funneled into STEM and business careers, while those who study the liberal arts desperately search for ways to make the field profitable. The distinction between life and career slowly fades as students are placed securely into a life within the marketplace. In opposition to this current trend towards mass commodification stands the withering tradition of the liberal arts education.

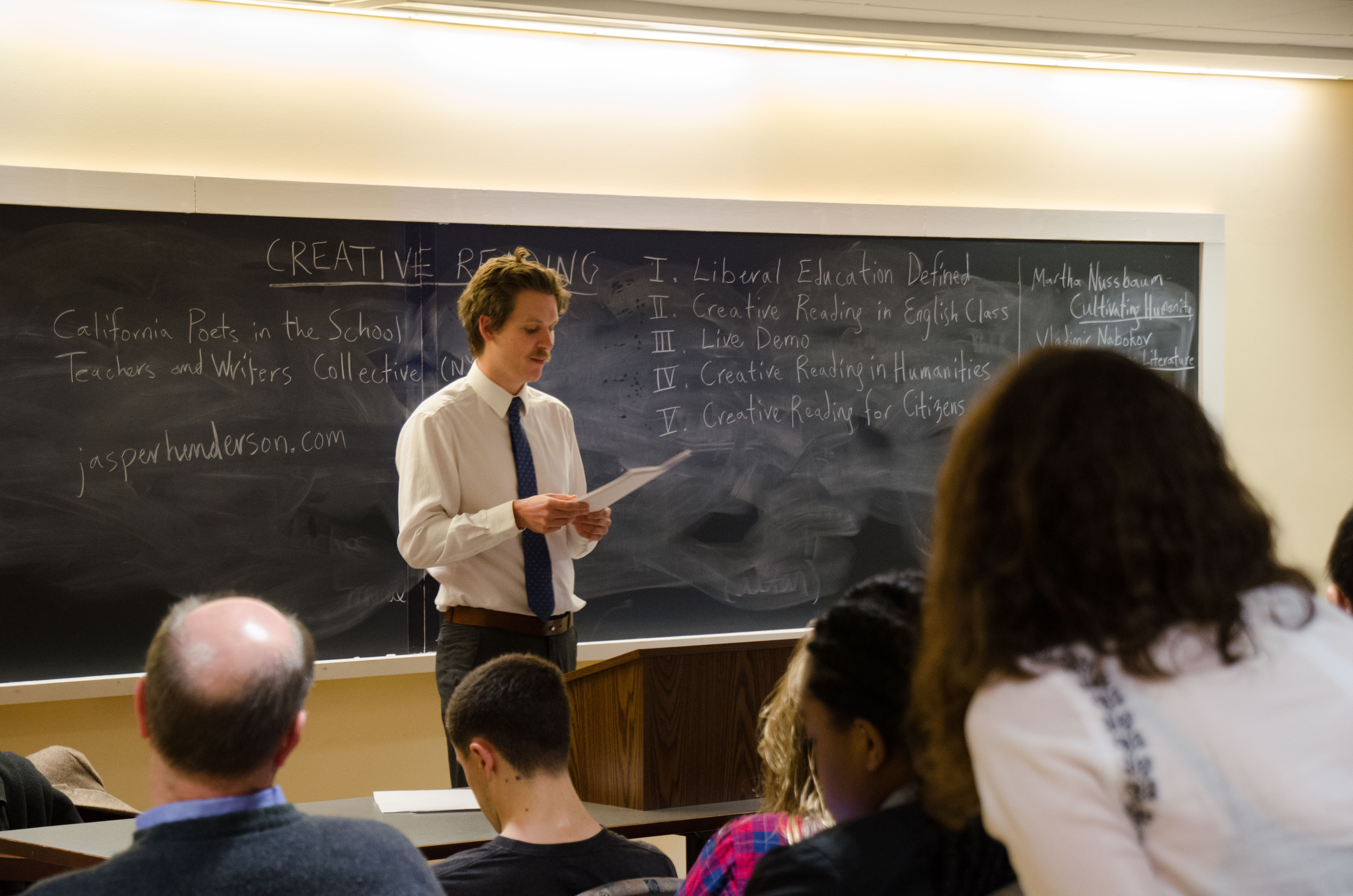

Jasper Henderson’s lecture on creative reading in Downey 113 this past Thursday began by asserting the necessity to fight for this liberal education, focusing on academia itself. Henderson, a teacher in California with a B.A. from Harvard in Slavic literature, discussed how, even in our humanities and social science classes, we are frequently taught to only examine texts by searching for interesting details that we can then cobble together in class. In doing so, however, we forget that we are looking at another breathing space, a place where we can escape our own perspective, if only briefly. The principal part of the lecture focused on ways to rediscover the experience of reading that came so easily to us in childhood, to regain that sensation of walking through furs you felt when your parents read you “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe.”

The first technique Henderson explained was a writing exercise that he uses when teaching. Henderson described how he would have students write for ten minutes from the perspective of a minor character in a novel. The example he gave to us was Mr. Charrington, the innkeeper in George Orwell’s 1984. In Henderson’s descriptions of the world from Mr. Charrington’s perspective, the crotchety old man becomes more than a symbol to merely analyze.

Henderson continued to provide techniques for engaging with texts in less restrictive ways. Most of these involved the readers inserting themselves into the text by attaching themselves to a particular character or by reorienting the story’s setting.

One of the lecture’s most interesting points was Henderson’s discussion of the intended audience for these techniques: everybody. The tradition of American liberal education has always come from a place of privilege and wealth. Thus, the idea of an “examined life” outside of a career carries behind it the idea that privileged college students will escape the brutal market forces that have created their privilege. Henderson, however, focuses his message primarily towards elementary and high schoolers through a program called California Poets in the School. His approach serves as a reminder that accessing creative reading should have nothing to do with traditional ideas of intellect.

Toward the end of the lecture, Henderson opened the idea of creative reading up to a wider field than the humanities. He referred to William Burroughs’ work, in which the author compares historical scholarship to time travel. Similar to the way that fiction takes us into an imagined world, nonfiction and historical reading bring us into a past world. Henderson’s prime example of this feat was William Dalrymple’s “The Last Mughal,” which describes the shared rule of the British and Mughal empire in 19th century India. The passages read by Henderson displayed how the writer revived the past by engaging the reader’s creativity through his use of powerful details from primary sources such as spy dossiers and old letters.

In the last leg of the lecture, Henderson swung his ideas of creative reading around to look to the future, discussing what the ideas mean for a citizen. He based much of this discussion on Henry David Thoreau’s always relevant essay, “Resistance to Civil Government.”

“Under a government which imprisons any unjustly,” Henderson quoted, “the true place for a just man is also a prison.”

He went on to explain that what Thoreau does in the essay is imagine another world based on what would happen if citizens simply acknowledged that the government’s power comes from them and then peacefully refused its right to rule if it acted unjustly. By suggesting an alternate reality, Thoreau reminds us that our current society is not fixed, but is able to be reimagined and changed.

Henderson’s lecture ultimately cut deep into our current system of education and the ways in which we approach problems. In our relentless intellectual pursuits to find and examine what is effective, we often lose sight of the why. Why is it that we read stories, made up or real? Why are particular problems occurring? Henderson summed this idea up well with Thomas Pynchon’s famous quote: “If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about the answers.”

By learning how we can enter into and experience a text, we can learn to enter into and understand the social and political sphere as well. We can learn to take on new perspectives and imagine new realities. While Henderson never mentioned it, I find the best allusion for what he was describing to be Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he looks at how America’s racist past pours into its present, all the while keeping hope alive by imagining a brighter future.

“And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream,” he said. “It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

Just as we create old and new worlds when we read, we create a future when we live in the present.

-

三五豪侠传