This profile is part of an ongoing Argus series on Muslims, refugees, and other students on campus who may be negatively affected by the Trump Administration. To suggest a student, email Features Editor Saam Niami Jalinous at sjalinous@wesleyan.edu.

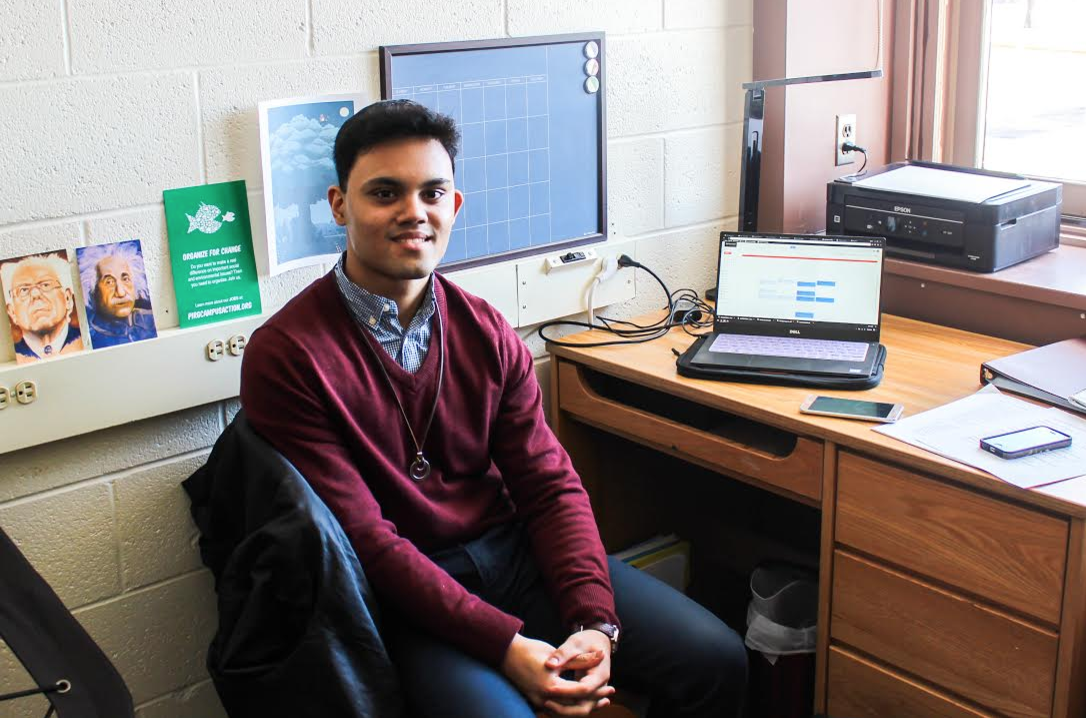

Munawar Rahman ’20 loves Sci-Fi, superheroes, and museums. He wants to be in a theater department show, and plans to major in Computer Science and Psychology. He has a drawing of Bernie Sanders on his wall in his freshman dorm in the Nics. He works out in his free time and his character glows of calm determination. Munawar, or “Muni,” as he’s come to be known at Wesleyan, is a Muslim from Queens. And he wants to be the change he wishes to see.

His parents are Muslim immigrants from Bangladesh, and his father is an engineer.

“When he immigrated from Bangladesh, all he had was his software engineering degree,” he said of his father. “He started working with computers in the States. Getting jobs, teaching people how to use them, and that’s where his career went. I got exposure to that at a young age.”

Muni plans to go into software development, hopefully working with accessibility or artificial intelligence.

“I wanted to incorporate psychology in my thing,” he said. “Because I care about the human condition enough that I want to make sure technology works for us.”

But Muni is worried about what his level of success may imply in broader cultural expectations of immigrants.

“A lot of immigrants, especially Asian ones, face the “model minority” stereotype, he said. “And at the beginning, I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s me.’ Model minority. Trying to be like my dad and do computer stuff. But that’s necessarily attached to the stigma of being brown in the United States. And then I realized, as much as I want to be successful in a career path, I don’t want to conform to that stereotype, and be an example that is used against others. Like people will point at black people in the U.S. or Mexican people, and then point at me, or Asian students, or white students, and be like, ‘Why can’t you be more like them?’”

Muni is also extremely politically active, stemming from his extensive reading of sci-fi and novels.

“My Facebook feed is just a bunch of very far-left liberalism,” he said. “Since I’m from New York, despite being in the city, I never really went out much. I would read a lot. Read a lot of Sci-Fi. Read a lot of novels. That’s what got me into the world of theater and the world of social justice. I took English classes, and my teachers were like, ‘This is what the world is like.’”

Muni’s interest and dedication to social change have made a profound effect on how he views the country he was born in.

“Reading about that made me kind of cynical about the U.S. in general,” he said. “Things are swayed toward people of a specific color. [The U.S. has] always been anti-immigrant; before it was white immigrants and now it’s gotten phased out. Anti-German. Anti-Italian. Anti-Irish. But now it’s, ‘Oh, brown people.’ We’re linked with both immigration and terrorism. Just being skin-colored brown. Even if we weren’t associated with those two things, they’d be like, ‘Look, their skin’s a different color. Boohoo.’ There’s an element of being a South Asian in particular. I’m not Arab, but my family is Muslim. So I’m stuck with those two things. I’m the immigrant that America wants because there have been news stories about engineering students not being allowed back into the U.S., and people are like, ‘Oh, we’re missing out on their talent.’”

Muni isn’t very connected to his parents’ religion, but the recent Muslim ban has been causing overwhelming fears for his family and for the state of the nation.

“I’m not particularly religious, but I still go to religious events with my family,” he said. “When we went to a Mosque in New York, over the years they’ve had to ramp up the security, even though we were in Queens and we were in a South Asian neighborhood. Just because we’re in the liberal bubble in the Northeast doesn’t mean there aren’t attacks on us. Or that we aren’t fearful.”

Muni isn’t only critical of American institutionalized racism. He also holds contempt over other Asian immigrants who won’t take action, like his own parents, but he understands the reservations.

“My parents aren’t really into American politics, they try to stay out of it because they knew they would be seen as ‘the other,’” he said. “They’re fully aware of that. But they didn’t want to get involved in it too much. Whereas, I feel like a lot of immigrants have the same perspective, [they’re] very conservative on some issues. They know that a lot of American society is largely against them. I wanted to cross that barrier. I’m not an apathetic immigrant. I want to care. I want other immigrants to care as well. I went to a high school which is the opposite of Wesleyan. In terms of demographics, [there were] a lot less white people, a lot more Asians. The Asians were the majority and it was very STEM [oriented] school. A lot of people didn’t really care about the world at large, so I wanted to avoid that, because I feel if that happens, that’s what leads to things getting fucked up.”

Muni feels a moral and societal responsibility to be bigger than his stereotype, even though it may be easier to just duck his head down.

“If I stuck with the model minority thing, I know I’d be less worried about the world at large in general,” he said. “Like, ‘Yeah, that’s what society’s like.’ But now I’m like, ‘I don’t want to be apathetic because I know I have a part in changing that.’ I have a role in speaking out, and being like, ‘Sure, we may be the stereotypical immigrants who come here and work hard, but that doesn’t mean we’re not going to fight for people who already live here.’ People who are being discriminated against right now. We refuse to be used as examples in the wrong way.”

Muni has found ways of connecting with his creative sound through theater, even bringing in elements of social justice into his creative passion.

“I did a program in New York over the summer,” he said. “We wrote our own scripts based on experiences. For instance, I did a piece on reactions to Black Lives Matter, and stuff like that. And I also worked with a kid whose father was shot, [his father] was a bodyguard. [He was] a black kid from New York. We got to put on pieces and performances based on that. That’s just been my experience with theater before coming to Wes.”

Munawar “Muni” Rahman is just like every other kid from New York, he loves Bernie Sanders and theater. He just looks a little different from the rest of them. But he doesn’t want to deny his skin color, he doesn’t want to ignore his family, and he doesn’t want to fit into a positive stereotype, because it’s still an expectation other than his own. He is searching for normal when he doesn’t fit into the assumed American “normal.”

“It just makes me sad and disappointed,” he said. “There are certain parts of the country that I can’t even visit or else I will be more and more aware of my identity. I feel that’s a double-edged sword. It’s nice to be invisible sometimes and just care about things like studying and television shows and video games and stuff. But I feel at the same time I need to know who I am or else I’ll just lose myself and become another detached example.”

Comments are closed