c/o static.rogerebert.com

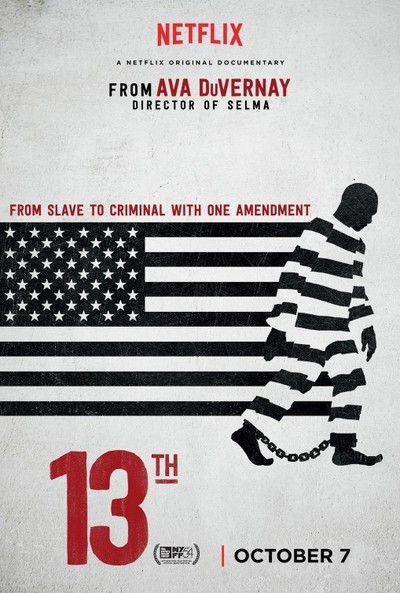

“Criminal.” Director and writer Ava DuVernay argues that this is a highly subjective phrase. As American political and economic institutions have evolved since the Civil War, one element of their framework has remained a constant: the deliberate criminalization of various activities as a conduit to deprive African Americans of their civil rights. DuVernay (who directed “Selma”) explores this theme in her new Netflix documentary “13TH,” a wide-ranging and empirically rigorous examination of the U.S. criminal justice system. Its cast of characters is a who’s who of criminal justice reform advocates, including Michelle Alexander, Van Jones, Angela Davis, Cory Booker and Bryan Stevenson. The cinematic manifestation of “The New Jim Crow,” “13TH” traces the historical evolution of racial disenfranchisement. It contends that oppression is ingrained in our legal system, reinventing itself using increasingly opaque language, but with no less severe consequences.

The film’s title refers to the 13th amendment of the Constitution, which prohibits slavery in the United States, except as a punishment for a crime. “13TH” claims this clause is a critical loophole in the criminal justice system because it creates the potential for a form of “legalized,” but no less immoral, slavery. The film is at its most incisive when it peels back the layers of the labyrinthine procedures that govern our criminal codes in an effort to understand why laws are written and who they are written for.

“13TH” opens with a soundbite from President Obama, explaining that the United States represents only five percent of the world’s population, but holds 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. How did we get to where we are today? The film strives to answer that question by rewinding to the Reconstruction Era South, where white plantation owners were struggling to accept that the end of slavery had deprived their economy of its most precious resource: the ability to exploit free labor in the plantation system. The landed class was able to maintain its racial and economic hegemony by passing “black codes” that denied African Americans property rights and allowed law enforcement to arrest them for fraudulent vagrancy charges like “idleness.” Those who were found in violation of these laws were auctioned off to plantations or forced into a system of involuntary labor and debt bondage know as “chain gangs.” These so-called criminals built a new infrastructure for the agrarian South, toiling in the very same conditions that they had supposedly escaped. As one African-American army veteran declared, “If you call this freedom, what did you call slavery?”

“13TH” continues by exploring the social consequences of Jim Crow-era legal restrictions and the Plessy v. Ferguson doctrine of “separate but equal.” One critical moment is the release of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film “Birth of a Nation,” which is largely credited with inspiring the second era of the Klu Klux Klan. The film was highly influential for the white power movement; it was the first film to be screened at the White House and it perpetuated stereotypes of the hypersexualized and aggressive black male. The Klan actually coopted their haunting ritual of cross-burning from the film.

“13TH” demonstrates the pervasive impact of racial stereotyping on our legal system by recounting the tragic fate of Emmett Till, an African-American teenager who was lynched at the age of 14 for allegedly flirting with a white woman. An all-white jury acquitted the defendants in the case of all charges. Jurors who were interviewed after the trial did not contest the guilt of the defendants in the case, but simply stated that they did not believe the killing of a black man deserved the punitive punishment that Mississippi law demanded.

Not to spoil the rest of the film, but “13TH” shatters any illusions that contemporary society is a “post-racial” utopia where the victories of the Civil Rights Movement and the election of an African-American president imply an end to legalized racial discrimination. The documentary declares that in a post-Jim Crow era, slavery is perpetuated through mass incarceration. The presidencies of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan sparked the trend of politicians leveraging “law and order” and tough-on-crime rhetoric to enforce a War on Drugs that caused prison populations to balloon in size from 200,000 in 1971 to 1.2 million by 1990. When crack cocaine possession is penalized at 100 times the rate of powdered cocaine, it’s no surprise that usage rates for each drug are divided sharply by race. However, the documentary also argues that the creation of a carceral state was a bipartisan effort. Those viewing the film in this election cycle may pay particularly close attention to the film’s analysis of Bill Clinton’s 1994 Crime Bill and the proliferation of punitive policies in that period, including harsher mandatory minimum sentences, stop-and-frisk, and three-strikes laws.

“13TH” makes the case that America has never truly gotten over the Civil War. Through every stage in American history, systemic racism has shaped the construction of our legal system and governed political debates over how to address the oppression that marginalized communities face. Even when policy and rhetoric become more abstract in their appearances, their consequences are no less damaging. The documentary’s discussion of contemporary prison conditions and the range of services denied to ex-inmates is chilling, its juxtaposition of images of Civil Rights-era brutality with the bigotry on display at Donald Trump’s rallies even more so. The clarity of DuVernay’s narrative voice throughout the film is gripping, and her message is clear. Racial disenfranchisement has not ended, and if we grow complacent in the fight against injustice, we will all be implicated in the complicity of past generations.

Comments are closed