Under the same bright blue sky, just up I-95 and a little further up I-91 from the World Trade Center, College Row and Foss Hill basked in sunlight as Wesleyan University students and faculty began getting ready for the second day of classes at 8:45 a.m. Until tragedy struck, and everything changed.

The Wesleyan community—from students and faculty in 2001 to those here now, including members of the class of 2020, most of whom were toddlers at the time—has a collective memory of 9/11 that ranges from huddling around TVs in the student center, watching from a middle school classroom and then deciding to enlist in the military years later, seeing kindergarten classmates mysteriously get picked up by their parents, to not remembering the day’s events at all.

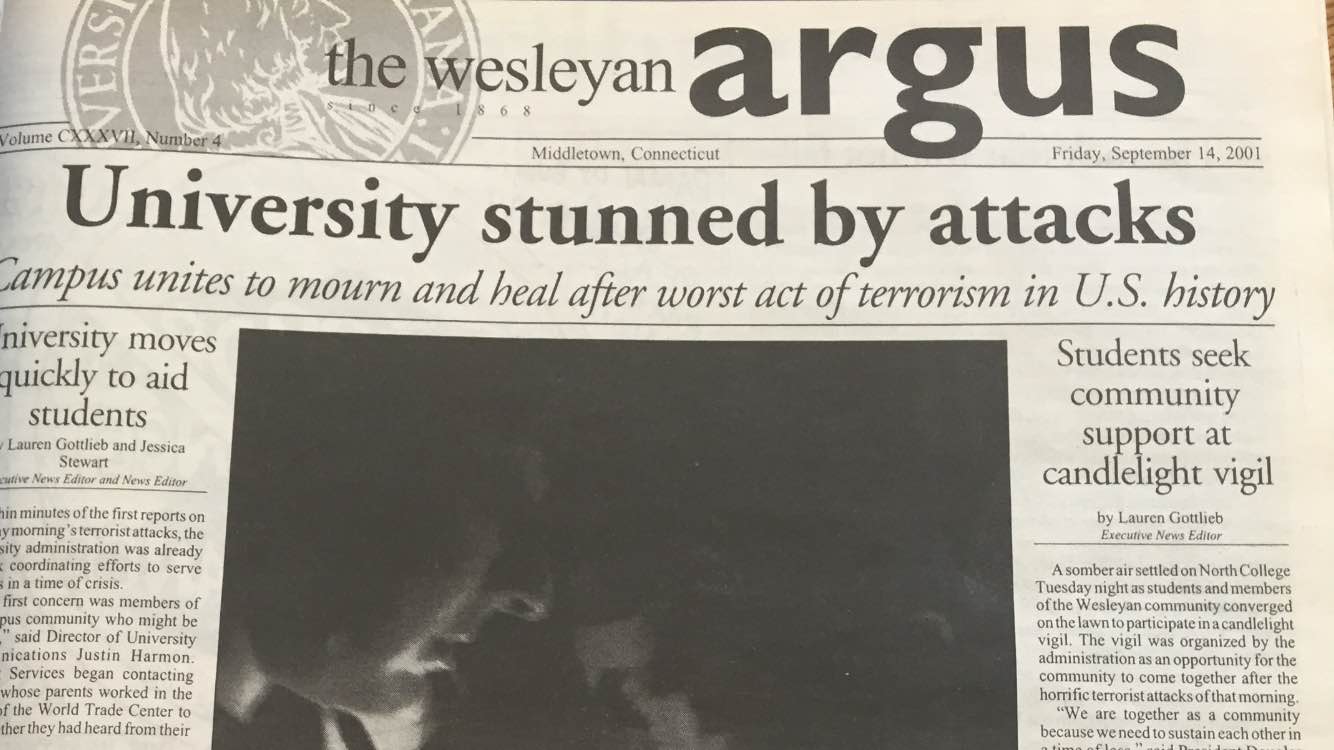

Primary sources such as the Friday, Sept. 14 edition of The Argus, along with interviews with current students and faculty provide a look into the trauma of a day that not only saw nearly 3,000 lives lost in fewer than 20 minutes, but also forever changed the world and even defined an era just one year into the 21st century.

At 8:46 a.m., a plane crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center in downtown Manhattan, which only seemed like a terrible accident at the time for anyone watching the morning news. At 9:03 a.m., a second plane crashed into floors 75-85 of the South Tower on live television, and suddenly the United States was at war.

Then the phones began to ring, eventually reaching the over 200 million calls that shut down phone lines in the United States.

One of the early calls that got through came to Cheryl-Ann Hagner, now Director of Graduate Student Services, who was at the time just starting out working in the archives in her first year at the University.

“I was home getting ready for work, and a friend called and said, ‘Turn on the TV,’” Hagner said.

Hagner was shocked, but the second plane hadn’t hit yet, so she went about her day and headed over to Olin Library for another day at work.

Professor of Government Marc Eisner was in his office on the third floor of PAC when he got a call from a former student working for the DNC telling him to turn on the television. He headed over to the Davenport Campus Center, now known as Allbritton, and saw students focused intently on big-screen TVs.

“There were a lot of students watching on the screen as the towers fell,” Eisner said. “There were some deans coming in to get specific students, for example if a parent was downtown….A former student of mine lost his dad in the World Trade Center. He was probably one of my favorite students, Ray Sanchez [’01].”

Meanwhile, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, Andrew Rock ’17, who was six at the time, distinctly remembers waking up on 9/11 and going to school, where parents began picking their children up from school unexpectedly as the day went on.

One of the last of the millennial generation to have been old enough to remember 9/11 out of all the students currently at Wesleyan—with the notable exception of Posse Veterans on campus, along with graduate students and any Cardinal born before the late 1990s—Rock’s more prominent memories came after that morning.

“My memories of the days after are more vivid,” he said. “I remember standing in the park next to the West Side Highway watching truck after truck carrying rubble approach from the direction of Ground Zero.”

Maggie Rothberg ’20, on the other hand, was only three years old on 9/11, and has no accessible memories of the day itself.

“Pretty much all of the adults in my town [in Westchester, N.Y.] commute to the city for work,” she said. “In second grade, on the anniversary, our teacher read us a book called ‘Fire Boat’ about a barge that came to rescue people, and that’s how I found out about it.”

When asked what the event means for her without any recollection of the tragedy as it unfolded, Rothberg painted a picture of a changed world.

“People our age are told over and over that America became a completely different place afterwards,” she said. “Not only that the event itself was traumatic, but that the way that it fundamentally altered our society is all that I’ve known.”

While most of the University population approaches no direct memory of 9/11 with each successive graduating class, Posse Veterans on campus have much more thorough memories of the day, which for many influenced their decision to serve their country in the wars that followed the attacks.

Though not the case for all Posse Veterans or those who served in Iraq and Afghanistan more broadly, some veterans at the University, such as Andrew Olivieri ’18 and Josh Wadlow ’18—both of whom were in the inaugural class of Posse Vets—were deeply influenced by 9/11 as adolescents.

Wadlow was 15 on 9/11. At his high school in Phoenix, Ariz., he has a common memory of watching a television in a classroom in shock over what was taking place before his eyes. What was uncommon for Wadlow, however, was that he found himself in the one percent of Americans who served in the wars that followed that day.

“I remember all of my friends were in this together talking about how they would join the army that day,” Wadlow said. “I joined a while after [9/11], but I don’t know if it would have been as big a consideration if 9/11 hadn’t happened.”

Olivieri, who was living in Washington Heights in Upper Manhattan at the time, didn’t enlist until 2009, after the surge in Iraq was winding down and troops were being removed from the arena. However, his 9/11 experience motivated his initial desire to serve, which changed when he encountered Special Forces troops who were leaving Iraq.

“Hearing from their mouth about Iraq, that’s when I started to realize that maybe my childhood understanding of the War in Iraq is really fucked if I have people who were there telling me it was fucked,” Olivieri said.

He then elaborated on what his fellow troops saw as the major deficiencies with the Iraq War.

“Mainly they said it was pointless, that they were doing missions for nothing,” he said. “What it came down to was that they were doing missions and they weren’t picking people up. The situation wasn’t changing, and the Iraqi government didn’t want us there, so the point felt moot.”

The War on Terror at large, however, is a complicated and multifaceted operation that Olivieri emphasized was not monolithic, and that operations like his in Afghanistan were more thorough and justified than those of his comrades leaving Iraq.

“There’s two different interventions that we’re talking about: We’re talking about the war against Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, and we’re talking about the War in Iraq, and the War in Iraq was a trumped up piece,” he said. “That was a totally unjustified war. In my mind, the War in Afghanistan was completely justifiable. The way that some people just look at the War in Afghanistan was that we were trying to overthrow a foreign and sovereign government, when in reality Al-Qaeda is a foreign entity in Afghanistan that’s using it as their base of operations, and the same thing with the Taliban.”

Hagner was also deeply affected by 9/11 in her actions after the phone calls came in around 9:00 a.m. and the TV huddles in what is now Allbritton dispersed. Over spring break later that year, Hagner took a group of students to St. Paul’s Chapel by Ground Zero, also known as “The Little Chapel That Stood.” A full van of near 20 students left campus at 5 a.m. to help out.

“The church became a sort of home base for supporting the workers who were doing the demolition and the relief efforts,” Hagner said. “They did uncover a body the day we were there, and we certainly didn’t all rush out and press our noses to the window to see, but we made sure to be extra sensitive in talking to the workers who came in.”

Back at Wesleyan the morning of, The Argus was printed that day since it was a Tuesday, but final edits were made late the previous night before the paper was sent to the press. That Friday, however, The Argus ran a rare full page headline entitled, “University stunned by attacks.”

Other headlines read, “Speakers caution against inappropriate reactions,” “Campuses across the nation change class schedules,” and “Campus members reflect on how they found out about 9/11.” The latter, written by Features Editor Alden Ferro ’04, was a more somber take on the section’s “Roving Reporter” column, where he interviewed several students and faculty with one simple question.

One respondent, Jordan Goldman ’04, who was an RA in WestCo 1 at the time, found out the hard way.

“One of my residents who I have Intro Sociology with came into the bathroom and she said, ‘Do me a favor, because I’m going to be late for class; tell the teacher that my mom works in the Twin Towers,’” Goldman said.

The RA found out upon arriving in class what had happened.

Editor-in-Chief Lydia Wagner interviewed Richard Sewell ’99, who gave a firsthand account of the attacks as he exited the subway near the towers as people rushed toward him in an effort to escape.

The Sept. 14, 2001 edition of The Argus also featured a controversial opinion piece by then-first-year student Nancy Wassner ’05, whose America-had-it-coming sentiment mixed with Zionism crossed typical ideological lines at the University.

“So when I woke up on Tuesday and heard a radio announcer decrying ‘this attack on our country, our nation, our lifestyle,’ I was a little confused,” she writes. “I thought I was dreaming. I thought I was back in Israel. And I began to laugh. For fifteen full minutes I couldn’t stop laughing. The irony was just too much for me.”

Alumni Colleen Ryan ’00 and Mark Alifanz ’99, who were attending the Harvard Business School and George Washington Law at the time, respectively, responded to Wassner in the next edition of the paper.

“First of all, we don’t care how ironic you find the situation; it is not a laughing matter,” they write. “We don’t care if the U.S. is the most evil empire in the world — there is NO EXCUSE for attacks against civilians. If we simply let the bastards who did this get away with it, we would be their equals.”

Eisner remembers a divided campus following 9/11.

“There were the obvious divisions on campus between those who thought that the U.S. had it coming and those who actually knew people who had died in 9/11, and that carried over for a while,” he said.

Looking toward the future amid such trauma, students predicted what would come next for the United States post-9/11, and many students were powerfully prescient.

“A rise in hatred and bigotry,” David Mane ’03 said.

“Going to an airport will be like going into a club,” Danny Rodriguez ’04 said. “It will be a lot harder to cross the borders.”

The Wesleyan community has coped with the trauma of 9/11 in radically different ways, from those who served in war to alumni like Himanshu Suri ’07 (a.k.a Heems), who was Vice President of the Student Council at Stuyvasant High School just blocks away from Ground Zero, left with an increasingly xenophobic and Islamophobic America that he critiques with his music in groups like Das Racist! and Swet Shop Boys.

“Oh no, we’re in trouble / TSA always wanna burst my bubble / Always get a random check when I rock the stubble,” Heems raps in his new single “T5” with star of HBO’s “The Night Of,” Riz Ahmed (aka Riz MC), for their new rap duo Swet Shop Boys.

How the University community will continue wrestling with 9/11’s legacy in the 21st century remains to be seen, as well as whether the mantra of “Never Forget” will hold up as a generation of students who don’t remember the day itself populate the campus.

Comments are closed